QUADERNO 8

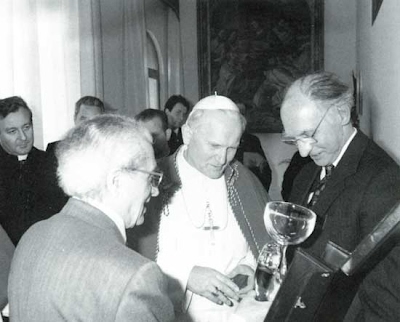

Historic photo: In this glimpse of the past, we present one of the most significant moments in Archimede Seguso’s long career: March 23, 1980. the day he presented a figured chalice to Pope John Paul II, honoring the fifteenth centenary of St. Benedict of Nursia. It is an original portrayal, in glass, of the Virgin holding a chalice; it is both a symbol of Archimede’s skill and of his profound faith. Therefore, it is no coincidence that for Christmas 1995, along with this picture which is already historic, we are proud to present Archimede Seguso’s Nativity scenes. We would like to wish all our readers a Merry Christmas and a happy holiday season.

PRESENTATION

“CLARITY”

This, the eighth issue of the “Quaderni di Archimede”, marks the end of the second year of an initiative that has met with a more than positive response. Our publication (as was stated in the first issue) is not meant to be a mere promotional tool, rather it is a vehicle or better, a window on an artistically significant type of product and production. It is glass – the field in which Archimede Seguso is the undisputed leading “maestro” in Italy – that prompts us, on the threshold of another two year period to use transparency and hence clarity as the main subject of a discourse that is not meant to be simply laudatory. It is more than obvious that, in this difficult period in our country’s life, there is a great need for clarity. We are going to talk about light in this issue, that is lamps and chandeliers. Clarity, however, is also a search for truth in addition to honesty in one’s work, and that means providing the public with correct information.

No hypocrisy, and no hidden meanings. “Archimede Seguso”, the firm, wants to be as transparent as its glass. It is its own interface and behind its crystalline image, there is its long history that is one with the history of Venetian glass during this century.

These “Quaderni” or notebooks were created as a mirror of a clarity that is conceptual in addition to being commercial. Unfortunately, in the world of industry, and that of glass-making in particular, it is not always like that. Unpleasant things occur, things that leave a bitter aftertaste. We, however, will continue to demand clarity: clarity for our glass, for ourselves and for those who so kindly follow us.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

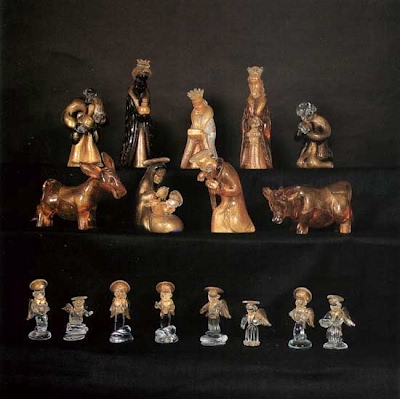

Nativity of thirteen characters, solid transparent glass with gold, 1992. h from cm. 30.

CHRISTMAS

The Nativity of Archimede Seguso. Works of art soaked with luminous transparency, the Nativity scenes, made over the years by the master of Murano are expressions of a great technical ability and a unique plastic and chromatic sensitivity.

The Sacristy of Santo Stefano in Venice is like a museum. Beneath Tintoretto’s masterpiece, The Last Supper, on a massive late seventeenth century chest, stands Archimede Seguso’s glass Nativity Scene. There seems to be a thread of light between the transparent goblet that Jesus holds in his hand and the golden glass of the Nativity scene. All around, the sacristy is dark and grandiose. On the other side is yet another masterpiece by Tintoretto the “Orazione nelI’orto”, a painting covered by luminous vibrations. Further along, on the high, severe walls there are two enormous canvases by Gaspare Diziani and Sante Perando, that balance out other famous paintings: a stupendous work by Palma Vecchio, two by Bartolomeo Vivarini and the very Baroque, Mazzoni.

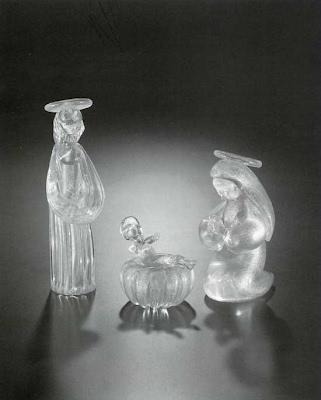

Nativity made up of three characters in solid transparent glass with gold. h cm. 18; cm. 14; cm. 7,5.

The large Nativity scene that Archimede Seguso made in 1966 is considered one of the Venetian master’s most important works, certainly the most significant one in terms of a religious subject. The characters develop and strech out harmoniously in a curved rhythm rendered evanescent by the reflections of the golden dustings: the glass fabric is submerged, here and there in opaline that covers a whole range of delicate tones, from pale blue to ochre to antique pink. It is the only twentieth century artwork in the monumental Sacristy of Santo Stefano. When the lights are turned on, it seems as if a spiritual glow surrounds the figures. And the viewer cannot remain unmoved. There is something Gothic in the tangle of forms and shapes, even though everything seems to obey the flow of curved lines and lets us feel the echo of a modern symbolism (Barlach). We can say that the clearest comparison is with the two figures by Vivarini and then we discover that both artists, the Gothic Bartolomeo and the modern Archimede – with five centuries separating them – both come from the same Venetian line…Or is it merely a suggestion?

Nativity in opaline, gold and soft toned glass, kept in the Sacrestia di Santo Stefano in Venice, 1966. maximum h cm. 80.

Archimede Seguso’s sculptorial dimension, that is his quality in being able to combine the statuesque with such a fluid and transparent material as glass is revealed in the many Nativity scenes the maestro has made since the ‘thirties. They easily merge with his historic solid glass “animals” and the female figures (like the famous iridescent “Dormiente” dated 1951, or if we want to go farther back in time, the nude “Donna che si spoglia”/”Woman Undressing” 1934).

Parallels have already been drawn between these, other glass sculptures- and the works of the great sculptures Archimede has known throughout his life such as Arturo Martini, Marini Marino and Francesco Messina. The distinctions between the fine arts and the so-called decorative arts have been overcome, especially when we are confronted with solid pieces such as these by Archimede Seguso, there is no doubt: they are art.

Nativity of twelve pieces, colored, blown glass with gold, 1950, Madrid, Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas.

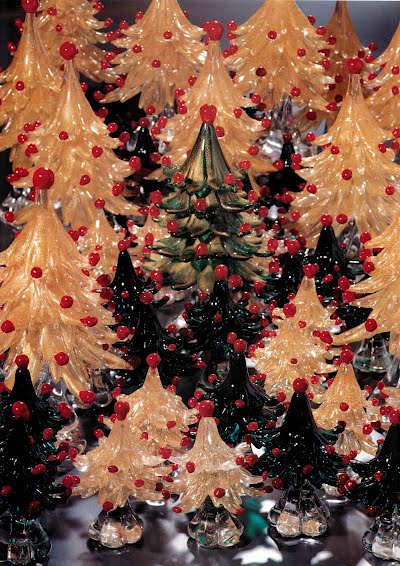

The Nativity scenes are the moment in which the master from Murano transcends the dimension of the single artwork and creates groups of human and animal figures in a certain striving for the ideal of a plastic reconstruction of the whole setting. In this he seems close to Arturo Martini and even Henry Moore, especially when the English sculptor engages in his “conversations” in an open, multidimensional space. This development of the plastic relationship is evident in some of the Nativity scenes, that reveal a rhythm of measured pauses and connections. Actually, it would be enough to mention one other famous Nativity Scene that is, the one he made in 1950: twelve pieces of blown and colored glass with gold, on display at the Museo Nacional de Artes Decoratives in Madrid. In the last few years Archimede Seguso has made more than a few Nativity scenes, most of which are gilded glass. They are distinguished by extraordinary elegance that develops harmoniously in accordance with the “Sacred Conversations” of the sixteenth century, rather than classical, Jacopo Bassano-type Nativity scenes. Obviously, there is an echo of that great Venetian culture which is part of Archimede’s heritage: the sense, even in the plasticity of the glass, of the “chromatic” atmosphere that permeates the paintings of Titian and Palma Vecchio. Another outstanding feature is the molten gold leaf that dissolves into a shower of dust, in the glass and dialogues, as it were, with the delicate colors, from pink to pale blue, which are so skillfully submerged in liquid transparency. The Nativity scenes are also embellished with some more worldly touches, such as the Christmas trees with red berries: exquisite items that in a sense reflect the spiritual aspect of the main subject if for nothing else than the fact that they are made with such sublime skill.

Actually we are only starting to also realize this one of Archimede Seguso’s priorities: the fact that he has interpreted the Nativity in a perfectly and unmistakably Venetian key. The manner in which this Maestro manages the glass and is able to reduce it to a pure essence through his technical ability and plastic and chromatic sensibility has no comparison. Perhaps, the only other pieces that can be considered in parallel are the classic Neapolitan Nativity scenes. It is no accident that the world’s great museums compete over these two aspects of Italian genius. On the one hand is the earthy, Neapolitan verve, symbol of a people’s extroverted liveliness; on the other, the temperate atmospheric transparency of Venetian color. Once again, we must acknowledge Archimede’s skill in having interpreted a great culture of shape and color – that is the Venetian – using contemporary language: just by taking a look inside the Sacristy of Santo Stefano is sufficient to realizing all of this.

CULTURAL NEWS

THE LIGHT

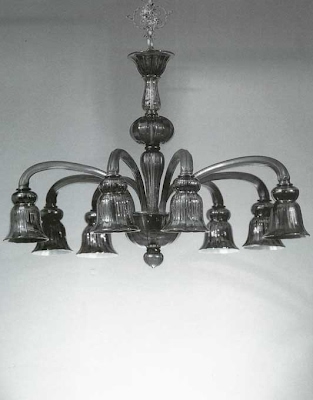

Optical science and aesthetic sense, the “feeling of light” and the magic of living live in the lamps and chandeliers of Archimede Seguso. Twisted, spiral, ribbed lamps which rise and chandeliers that extend into space, radiating an extraordinary luminosity.

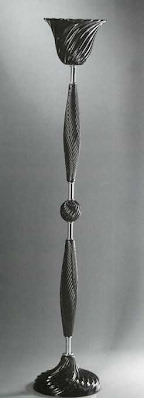

Lamp stand in twisted ribbed glass in ruby and gold, with gold crystal rings. h. cm. 185.

Light, the impalpable, ever- fleeting element that continuously escapes our grasp. Science tells us that it consists of electromagnetic waves emitted by luminous bodies: photons, quanta, frequency, refraction, wave length, radiation, and so on. Just recently the Vermeer exhibit in Washington has raised the issue of the sublime quality of light in paintings by the great artist from Delft; everything remains fluid, free of any real experimentation. Thirty years ago Kenneth Clark wrote “that is was Venetian painting that discovered the mystery of light.”

But the mystery remains. Perhaps some old Venetian formula can solve it. Perhaps some artist today can even come close to not quite a solution, but a hint of truth. We too can try to approach it. The master glassmakers of Venice, both past and present have always had to deal with the matter of light. It is fundamental to such an unusual material, a material as fleeting as glass, and especially when it becomes a source of light, refracting and diffusing it as well. It is here that Archimede Seguso is truly astounding. His lamps, be they on stands to be fitted with a shade, or actual chandeliers, lead a sort of double life, turned off and on. And it is when the light is on that function is sublimated.

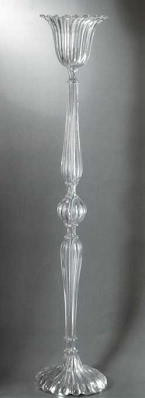

Bases, for lamps, in various forms and styles, smooth or ribbed, in transparent cyrstal glass, from green to ruby to yellow to white, with gold. h from cm. 50.

Ground blue glass with twisted ribbing. height cm. 185.

Ground crystal glass with gold straight edges with central ball. height cm. 185.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

THE GREENS

The “iridescent glass”, the latest creations of the glass master of Murano. Iridescent, pearlescent, which seem to constantly mutate into a kind of shimmering, almost a journey to the limits of the fantastical.

Iridescence is closely linked to the mineral quality of glass. In scientific terms it can be explained as a sort of interference due to minute air bubbles that infiltrate infinitely small cracks in the surface.

The optical effect is one of changing reflections of the spectrum: a magic show of colors that resembles a chromatic breakdown of the rainbow. In Greek, Iris means rainbow; she was the daughter of the Titan Thaumas and the ocean nymph Electra, and because of her ability to move and change so quickly, became messenger of the gods.

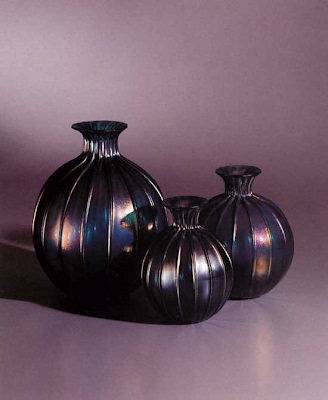

If we take a look at one of Archimede Seguso’s recent vases, with that phytomorphous elegance and ribbing, what strikes us first is the green color.

Vases, spherical shape, with light ribbing, iridescent green “Serenella” It h cm. 15; cm. 20; cm. 25.

It’s a strange kind of green, almost magic: it grasps iridescent, mother-of-pearl reflections in a constant sparkle. Chemically, it is this coloring that makes glass transparent or opaque, in an optically suggestive intermediate stage, and can be explained by impregnation by tin fluoride vapors. The vapors or smoke inside the furnace are practically imprisoned in the surface of the red-hot glass and amalgamate with it. The spectrum opens and nearly dissolves; and the eyes are astonished.

From chemical phenomena to esthetic transposition: this is where Archimede Seguso excels. These vases compete with the finest examples of Tiffany glass, especially those by Louis Comfort Tiffany that carried iridescence to the highest peaks at the turn of the century. Archimede Seguso uses it in a more subdued manner, beyond floral redundancies.

Vase with base and oval vase with light ribbing, in iridescent green “Verde Serenella 18”. h cm. 33 and cm. 21.

The vases that have come out of the furnaces at Murano over the past few months have a rigorous elegance consisting of essentially harmonies in patterns based mainly on raised ribbing created to highlight the magic of chromatic transmutation even more dramatically.

Iridescence emerges from its mineral shell alone, it is the vehicle for a journey of the mind that discovers new shapes within the sparkling changes, shapes that expand until they reach the boundaries of the fantastic.

Vases and pitcher with light ribbing, in iridescent green “Verde Serenella 18”. h cm. 40; cm. 32; cm. 32.

We can almost see Leonardo da Vinci leaning over these vases imagining battles and horsemen, mysterious forests and charming maidens. These “vapors”, as the master Archimede Seguso called them, become a bridge leading to an adventure in the unknown.

Chandelier, 8 lights, in iridescent green “Verde Serenella 18” with light ribbing. diameter cm. 104.

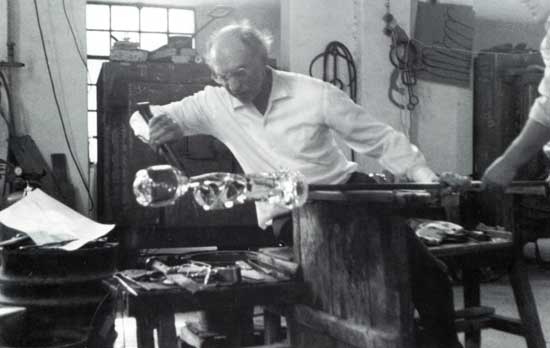

The Maestro Archimede Seguso at work in his furnace in Murano.

Back cover: Golden Christmas trees, in crystal or green glass, with coral decorations. Archimede Seguso’s window shops are decorated with these festive Christmas trees.. h from cm. 14 to cm. 32.