NOTEBOOK 1

Archimede Seguso is the most famous living master glassmaker, still working actively in Murano. He was born in 1909 into a family of glassmakers, when he was eleven, in 1920, he went to work in the glass factory where his father was one of ten owners.

By the time the partnership broke up after the crash of 1929, Archimede was already capable of working of his own. Since then, his pieces have been in continuous demand and have become famous, his work is featured in many museums around the world. An extraordinary technical innovator, he developed new shapes and styles and soon attained levels of sculptural art that would last throughout his life. His successful participation in major international exhibitions including the Biennale di Venezia has confirmed him as one of the dominant figures in twentieth century glassmaking.

FOR AN ART OF GLASS

That glassmaking is an art is a long-established fact. This is furthermore confirmed by a growing interest in fine collections. However, there are still too many misunderstandings both on the esthetic and commercial levels with regard to the entire world of glass. “Archimede Seguso” has a long and glorious tradition, and for decades has combined technical mastery with a highly individual creative spirit, linked to the prestigious name of its still active founder.

This publication has a specific aim: that of mirroring the “cultural momentum” that “Archimede Seguso” pursues. We are not presenting a mere sales tool, but rather and primarily a vehicle for artistically engaged glass production. The general plan of the entire publication has been designed for this purpose.

Even in the future it will be divided into three sections: the first a monograph on a specific subject related to glassmaking; the second, a glance at the past, that is the history of “Archimede Seguso”, and Venetian glass production of Murano in general; and the third a wide-angle view of today’s esthetic “trends”.

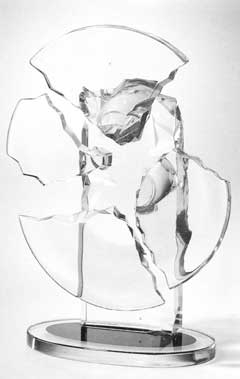

As the reader can see, this outline is used on the following pages, starting from the extraordinary “Rotture” cycle which has both cultural and social significance even in the purity of the medium.

We believe that the historical digression on the “nudes” of Archimede Seguso from the ‘thirties and the parallel with the pictorial culture from the same period will be extremely interesting.

Just as stimulating could be the “contact” with the more recent line of production, which has come to a reconciliation between the yesterday and the today, that is to a permeation of the authentic values of this great Venetian art of glassmaking.

“BROKEN” SIGNS OF THE TIME

A series of pieces out of the genius of Archimedes Seguso: moments of existential symbolism that extend to society. The mass is shattered, it separates, but is reconstructed into a new form of estranged beauty. The escape outwards, explosion, rotation: the sense of pain and anxiety of a spiritual light.

Le metà differenti, black ruby solid glass crystal.

Mis. cm. 36.

Divisions, breaks, lacerations: the tragic signs of our restless era. We talk about them, argue about them, we suffer their consequences, both on a cultural level and on a more general level that affects all of society. The recent history of painting also has some striking examples: from Vedova to Fontana to mention just two Italian artists. But what about the art of glassmaking.

It can be said that because of its intrinsic fragility glass is prone to breaking. It is easy to break a piece of glass; difficult to control the breakage. Archimede Seguso, the

Fragments in rotation, disks of broken glass set at different levels. cm. 42.

most famous living Italian glassmaker, has attempted what could seem to be the impossible: transforming a breakage into a means of recomposing (also of restructuring) the form. He has shattered, materially and symbolically and through this shattering he has rebuilt. He has thus given us a sign of hope.

These pieces by the artist from Murano were obviously born from inner reflection which then became trauma. Ever since he began going to the glassworks in the ‘twenties he has been accustomed to creating from a liquid and shapeless mass such as molten glass: creating from almost nothing, as stopping water or the wind. It’s an extraordinary exercise, that of manipulating that treacherous Friend-and-Enemy. One must know all its secrets and be able to foresee its metamorphoses and transmutations.

At the age of eighty-four, the great Archimede did not want to burn the enemy’s ships with his powerful burning glass, rather he wanted to burn an old platitude; that of shape or form, springing from the shapeless or formless. He broke the form with a sort of titanic will in an effort to make glass even more expressive in the moment in which it passes from the liquid to the solid state. The break has become a miracle, steady and fixed in time and space, almost frozen in a feeling of uneasy beauty.

I would not hesitate to say that these “breaks” by Archimede Seguso are among some of the most beautiful sculptures of our day, and certainly they are among the most emblematic.

Fragment restrained, ground clear glass decorated with blue glass. cm. 32.

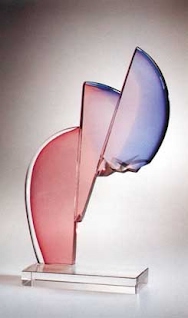

Something holding me, cobalt solid glass decorated with ruby glass, black crystal. . cm. 31.

They are born from great technical skill in handling and working with blown and solid glass. Transparency and elegant colours, from ruby red to cobalt blue, they seem to escape outward or rotate inward. They encompass shifts of plane and semantic transliterations; they carry a dynamic, untamed force that seems to be eternally changing. They strike our eyes and yet they sink into our psyche… This is the glass that at times shoots off a shard, or explodes irradiating into space. The stellar nucleus breaks down until it becomes a galaxy of lights and perhaps one lateral ray escapes even further. How can one not become involved symbolically in this anxious yet perfectly composed yearning for the infinite.The sensation of pain within seems to dissolve, and yet it merges with an ideal concept. The same parallels that can be drawn with similar experiences of the great painters and sculptors of this century have to move over and make room. Glass is a unique material: it does not suffer any violence, it is almost an introspective

Fugue and attraction, mass of shattered glass, submerged ruby crystal cm. 47;.

Softness violated, two oval solids overlapping, transparent glass and opaque stain in red glass. cm. 36.;

Fractures, ground ruby shaded light blue glass, black glass, sectioned into three parts. cm. 46

Split bounded, black ruby crystal solid glass . cm. 44.

Contrasts, primary geometric elements in black, purple, light blue crystal, cm. 35.

Split rhythmic, cobalt solid glass decorated with ruby and black crystal. cm. 32.

examination of its most intimate and secret qualities. It is similar to discovering latent energy and making it explode. This “operation”, that I could even define as maieutics, that is helping to bring forth the vital seed of glass, implemented by an octogenarian master is indicative of the integration that exists between the artist and “his” material. It’s as if, rather than physical energy, the essential element is spiritual energy. The “breaks” are primarily mental, like the cuts and holes were for Fontana. The esthetic quality bursts forth like a spontaneous fact, and we are amazed to see that there is no annoying intermediary.

Everything happens as if a force of nature were dissolving. Amazed, we admire these works born from the anguish of our era. We cannot do more than acknowledge the fact that they contain a beauty that goes beyond the boundaries of time. The eternal Beauty of glass.

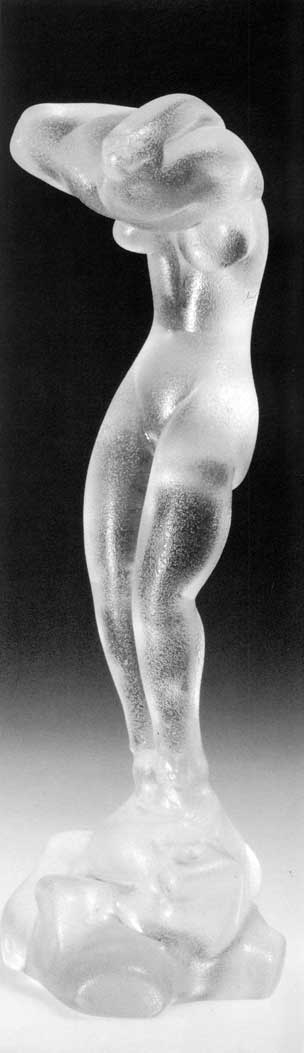

IN THE FABULOUS THIRTIES

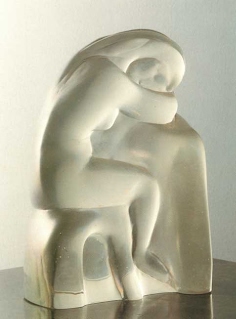

In 1932, Archimede Seguso sculpted in glass his first masterpiece. A new opening for the taste of the time: the union with Arturo Martini and the greatest artists of the twentieth century. The solid processing, the perception of the plasticity of the block, the sense of structure. Two basic elements: the technical skill of the young master and his cultural insight.

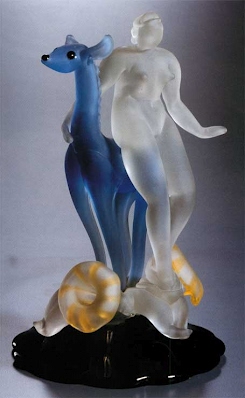

a Deer) in 1932, he was just twenty-three years old. He worked with his brothers at the Seguso firm which was also running the Salviati glassworks in Venice. In that same year, at the Biennale, Arturo Martini exhibited four masterpieces, including II Sogno (The dream) which is perhaps this century’s most beautiful piece of sculpture. Surely the young man from Murano saw and admired Martini’s work (perhaps even met him). The purity of line and absolute fluid plasticity of “Donna con Cerbiatto” are certainly part of what was then the most advanced taste in Italy.

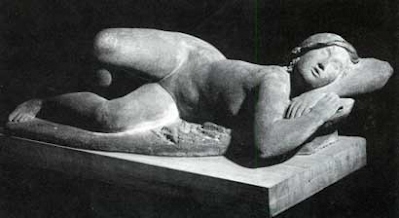

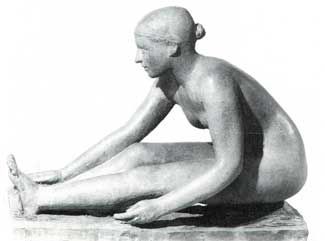

Today, it is difficult to get a feeling for those days. On Murano, after the 1929 crisis, the trend turned towards stereotyped neo-eighteenth century styles. Only a few artists understood that Martini’s classical nostalgia represented the symbols of a new culture that was moving ahead. Sironi, Casorati, Guidi, Funi and to a certain extent, even Carra, moved along with Martini. They were painters from different backgrounds who shared that typically twentieth century ideal of “Mediterraneity”, which primarily meant a reinterpretation of the great proto-Renaissance season. Marini (born in 1901) and Messina (1900) already had budding reputations, while Manzu (practically the same age as Seguso, born in 1908) was still looking at the models that evoked the Roman republic. But, aside from these individuals, a new climate was developing in Italy under the banner of the “Stile Novecento”, or Twentieth Century style. Archimede Seguso, always aware of new movements, attended each edition of Biennale and other major exhibits, felt that Venetian glassmaking had to come out of its old style shell and move in harmony with the times. He shared this outlook with other (just a few) glassmakers, with whom he worked to open new horizons in glassmaking. It is no coincidence that he, already considered one of the best master glassmakers, alternated his work between blown glass, typical of the traditional method of Murano, and the use of solid glass, that is, a material easier to use for sculpting. This is why “Donna con Cerbiatto” appears to be more of a harmonious classic rather than typical of Art Deco style. One senses, from the plastic synthesis, the modulation of a Renaissance curve (we can almost see traces of Donatello), which continue to develop into the stupendous “Dormiente” (Sleeper) that he would make in 1951, and beyond, the features that would become constants in Archimede’s entire “line”. During the ‘thirties, which today fit into more of a European rather than purely Italian aesthetic dimension; a piece such as the “Donna che si spoglia” (1934) (Woman undressing) reveals obvious parallels with the most famous sculpture of the period. Merely the dress above her arms is a plastic element that goes beyond any descriptivism. Even the pieces made after the war; such as the Nudo in nero iridescente (1949) (nude in iridescent black) and above all the “Dormiente” (1951) fit into a context that is very close to the sculptures by Messina, Marini and Manzu, with a certain propensity for Martini.

“Woman Undressing”, corroded glass. h. 30 cm Year 1934.

The most interesting facet of this decade on which there is so little documentation, is the large panel “Segni dello Zodiaco” (unfortunately unavailable). This panel, presented at the Triennale in 1937 shows the influence, as Umberto Franzoi so aptly noted, of great Tuscan Renaissance Art, along with a purely European modern taste, in the plastic synthesis that is both elegant and severe along lines that range from Laurens to Moore. In this piece, as in the others he made during the ‘thirties (and of course not only in the “nudes”), we can see Archimede’s skill, the extraordinary confidence and technical mastery and the great cultural background that gave them their strength. From the technical standpoint it is important to note that during the ‘thirties Archimede Seguso began working with solid glass, in the manner of sculptors and not in the traditional method of glassmakers by adding molten glass. This was a technical innovation. He wanted and knew how to bring glass closer to the world of Art. This does not mean that he abandoned the typical Venetian technique of glassblowing, with its filigrees, feathers and laces. But his Kunstwollen was clear. And to strengthen it he began with the worn, the bubbling, the opaque, the iridescent, the multicolored: techniques that were meant to give the material a plasticity of its own by playing on colours and light.

Presentato alla Triennale del 1937, questo pannello rivela un’ascendenza, come ha ben notato Umberto Franzoi, dai grandi esempi rinascimentali toscani, ma anche un gusto moderno tutto europeo per la sintesi plastica insieme elegante e severa, su una linea che va da Laurens a Moore. In quest’opera, come nelle altre degli anni Trenta (e non solo ovviamente nei nudi), si rivela la mano formidabile di Archimede, la straordinaria sicurezza e perizia tecnica e, insieme, il fondo di cultura viva che le innervano. Va sottolineato, proprio sotto l’aspetto tecnico, che in quello scorcio degli anni Trenta, Seguso inizia a lavorare il vetro massiccio su una massa unica, cioè alla maniera degli scultori e non a quella tradizionale dei vetrai con le aggiunte modellate a caldo. Questa era una innovazione tecnica. Archimede Seguso sapeva e voleva avvicinare il vetro all’arte. Non con questo che egli abbia allora abbandonato la tecnica tipicamente muranese del vetro soffiato, con i vari merletti, filigrane, piume, etc. Ma il suo Kunstwollen era chiaro. E ad avvalorarlo ecco l’uso del corroso, del bulicante, dell’opaco, dell’iridescente, del multicolore: tecniche che intendevano dare alla materia una sua plasticità, giocando sul colore-luce.

“Woman with Deer”, etched glass figure, transparent blue fawn. h. cm. 23. Year 1932.

Sculptural comparison: “Bather”, Marino Marini, 1927. “Woman in the sun”, Arturo Martini, 1932-33.

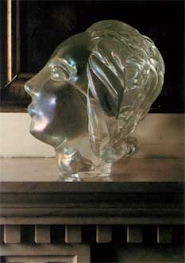

“Nude”, black iridescent glass. cm. 23 I. 1949, on the right, “My Wife”, head iridescent crystal solid, 1937.

cm. 22. Below, “La Dormiente”, solid iridescent crystal. h. 19 cm Year 1951.

ONE LINE, ONE STYLE: “INTRICO”

The new line of production of Archimede Seguso, a mobile unreality of filaments within a liquid mass. An escape of the matter into the non-matter: technical knowledge, enthralled suggestion. Expressiveness and uniqueness combined into a more lively sense of form. A serotine atmosphere quilted with very slight streaks of light and color.

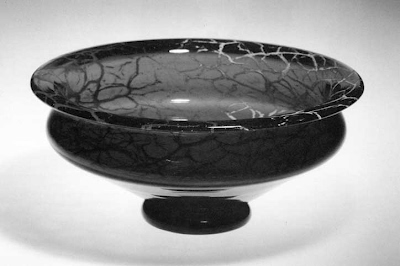

Coppa con base, coppa in vetro blucobalto e intrico difili di lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 33.

“Archimede’s atmosphere” cannot be touched, it is only felt. We could even call it a style. For several decades this great Venetian master glassmaker has been making pieces that continue to astound.

There is something in them that works on three different levels: 1) the artist’s independent personality; 2) adherence to the cultural climate; 3) understanding of the public’s tastes. Taken singularly not one of these components would be sufficient. Art is like this, and not only from the

Orsetti in vetro blu cobaltoconfili di lattimo e corallo, orso in vetro cobalto confili di lattimo. Mis. cm. 20 (orsetti) e cm. 35 (orso).

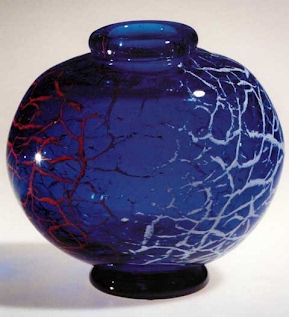

Vaso sferico con base, vaso in vetro blu cobalto confili di lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 21 x 22.

golden age of Picasso and Matisse: it is a clever and wise combination of personal and collective factors, of being in step with the times and ahead of them. And so, there is a new line entitled “Intrico”, and the term itself is… intriguing. Like the “Rotture” (Breaks) cycle we spoke about on the preceding pages, Archimede Seguso relates with a state of mind that is not only his own, but also collective.

“Intrico” is “a disconcerting and fortuitous combination of elements of confusion and obstacles”, but in symbolic terms it is a “situation that causes embarrassment and disorientation”.

An artwork is a shock. In this case the relationship with what is happening in our society at this point in time is indeed evident, but an esthetic element is also being evoked. We are all part of this “intrigue” that Archimede has so brilliantly visualized in a series of glass pieces. Art itself is intriguing, a kind of magic that enthralls, bewitches and bewilders us.

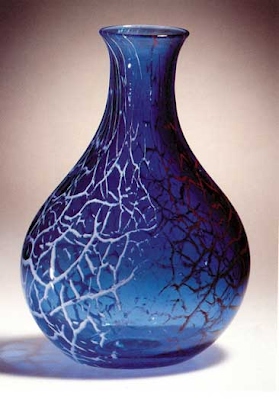

Vaso collo allungato, vaso in vetro blu cobalto con intrico difili lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 36.

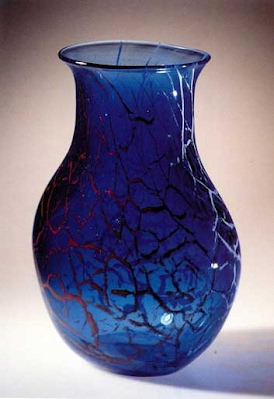

Vaso a fiasca, vaso in vetro blu cobalto confili di lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 35.

Let’s take a closer look at these new pieces. Technically, they are cobalt blue blown glass bubbles, crystal coated with milky glass and coral inlays. This unreal mobility of filaments moving inside a liquid mass merely to escape from our senses has an enormous attraction.

In the raised stands, the different shaped vases, bowls and plates, and even in the animal series (usually bears) a kind of mesh is woven and intertwined before our eyes. It seems to unravel and lose itself in space and then somehow, it is retied and rewoven in subtle shades that go from blue to white to red.

We are captured by this continuous flight of matter into non-matter, which is yes, so typical of glass (and which is part of its intrinsic charm), but which the skillful hands of the artist have taken to the utmost limits, steeping it in a serotine atmosphere, where a meshwork of filaments is about to settle.

Vaso fazzoletto con base, vaso in vetro blu cobalto confili di lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 30 e cm. 34.

Vaso alto, vaso in vetro blu cobalto e intrico di fili lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 28.

The external impression is strengthened by close technical scrutiny. These “intricate”, mysterious works are of extraordinary quality and totally inimitable. This is not because they hide the secret of how they are made, but because they bear the imprint of the artist’s personality. Archimede has received the public’s imprint, that is the trend of a fleeting style and at the same time he has guided its taste, in style. The research of the executive difficulties has always been a typical feature of Archimede Seguso’s work. Since the ‘thirties he has always tried to “go beyond”, perhaps by working the glass as one would work with a sculpture. And furthermore, to break away from set patterns in order to get closer to an ideal, to Utopia.

Piatto con base, vetro blu cobalto con intrico difili di lattimo e corallo. Diametro cm. 45.

The vitreous matter has become unique; the shapes (be they vases or chandeliers, nudes or animals, the lightest howls of blown glass, or solid, carved blocks) all respond to a “feeling for shape” which is always expressive.

This is why these “intrigues” created on vases or bowls, contain something that comes forth in expressions. Beauty is never something unto itself, closed in the neo-Platonic space beyond the heavens.

It is man’s way of putting his own feelings into matter. We see it as, almost in filigree, this “atmosphere of Archimede” expanding with lightness and elegance with the air and fragrance of eternal youth.

Vaso a trottola e Vaso uovo, vasi in vetro blu cobalto con intrico di fili di lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 25 e cm. 29.

Uovo, uovo in vetro blu cobaltocon intrico difili lattimo e corallo. Mis. cm. 12.