NOTEBOOK 2

The Seguso family, a photograph taken in 1926.

Standing behind his father Antonio, is second-born son Archimede.

At the age of seventeen, Archimede had already been working at the furnace for five years and was in the process of becoming “master”.

PRESENTATION

“CULTURE ON THE MOVE”

Here we are, the second edition of the “Quaderni di Archimede Seguso”, and we must say that we are extremely satisfied with how it has been received by the public in the past three months.

At the time of the “debut” we said that “Archimede Seguso” the standard bearer of a great tradition has, for a long time proposed a combination of fine quality and independent creativity, linked to the prestigious name of its founder who is still happily and actively working. These “notebooks” are meant to reflect a “culture in motion” rather than being mere commercial tools. This was also confirmed by the Treviso exhibition of Archimede Seguso’s cycle dedicated to “rotture” (breaks) that we talked about in the last issue.

It was a true success: in fact, after Venice, the show will go to Florence, Rome, Milan and then to several cities abroad.

This issue, like the previous one, will attempt to link the historical aspects of Archimede’s glass with a cultural situation that is closely linked to current reality. Archimede Seguso has frequently been described as a “modern classic”.

On the following pages, we present a brief overview of his major pieces in American, Japanese and European museums.

Then, there is a historical presentation that focuses on the master’s participation in the 1972 Biennale in Venice, the crucial year of transition, and finally an interesting glimpse of glass furnishings in a Venetian home.

Yesterday and today: the continuity of a great tradition and eyes open on a changing world.

CULTURAL NEWS

GLASS IN MUSEUM

Classic and universal, the glassy unreality of Archimede Seguso has landed in the temples of the Muses: from the Metropolitan to the Corning in New York, from Otaru in Japan to Vienna and Madrid in the museum of decorative arts. What is a Museum? We may answer that it is a Temple of Muses, or rhetorically one could say that it is a place where we collect and keep historical memoirs. Ernest Gombrich perhaps found the most appropriate definition: “Museum is Art that travels across time”. For the famous Venetian master glassmaker it is a custom that has been going on for decades. But it is only now that certain fixed ideological and aesthetic tenets have fallen away that we realize how certain arts, those which until yesterday were defined as “decorative” have finally entered the innersanctum. History is consistently welding the undisputed nobility of painting and sculpture to that of glass as an art unto itself, released of all functional restrictions or ornamental gilding. Therefore, it is logical even natural that Archimede Seguso’s glass compositions be found amongst the works of art in the major-rather in the most important museum of all, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, pieces included with the dignity of the art. They are art-simply art without any qualifying adjectives at all.

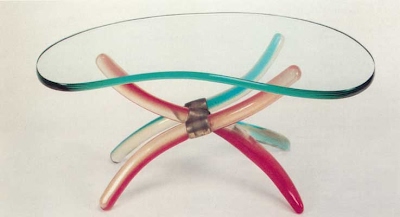

Table, 1950, clear glass top, legs red to green, marbled with goldleaf. New York, Coming Museum of Glass.

And how many museums around the world showcase works by this master? It is impossible to say because acquisitions are usually made via private transactions or auctions. For some time now Archimede’s glass pieces have been considered full-fledged contemporary art: that means they undergo evaluations and appraisals in relation to period, style, rarity and quality. After all, everything today has its price, Carlo L. Ragghianti, in the ’60s, decided to quantify the price of every piece of art in Florence including all the pieces by Giotto e Botticelli. Every day letters from prestigious institutions are received at the Murano offices of Archimede Seguso requesting loans. The most recent one arrived from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of New York which, on May 2, 1994, requested the loan of some pieces from the ‘fifties (contended mainly by the international markets) for a prestigious exhibit entitled “The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943-1968” scheduled for October.

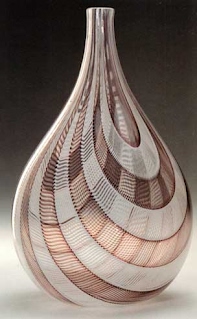

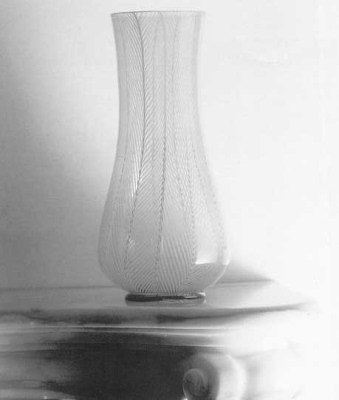

Vase in festoons, 1954. Drop shaped clear glass vase decorated with festoons of intemal straight diagonal segments in white and amethyst. h. 28 cm., diameter 17 cm. Kunstmuseum Dusseldorf.

Zig-zag Vase, 1951. Spherical vase, decorated with intemally spiraling zig-zag bands, coral and white with gold. h. 17 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum.

These pieces of the ‘fifties (today the most contended by the international markets) are amongst the most contended by museums for showings and even permanent exhibitions. Just to stay in New York, or rather to go back to the Metropolitan Museum, we should remember that among its many masterpieces the Museum has a vase made by Archimede in 1951: a sphere with a small opening on top, decorated on the inside with fine spiralling zig-zag bands, in an exquisite combination of coral and opaque white with fine streaks of gold. The vase came to the Metropolitan Museum during the great 1989 Tiffany exhibit which included an authentic celebration of Archimede, and it was purchased by the Museum’s trustees. Critics have praised this piece because it combines a daring taste-practically a formal break (the zig-zag bands) with extreme elegance of colour and shape. It was praised by many precisely because it expresses that which is called “Italian style”, in the sense that it unites classicism with linguistic innovation. The early fifties were golden years, not only for Archimede, but for all Italian design which is so esteemed by the entire world today. It is sufficient to mention that the only automobile on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is a red Cisitalia made shortly after World War II.

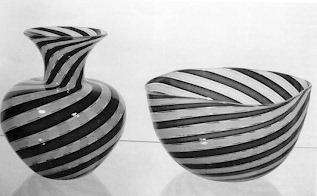

Vase and bowl, ribbon pattern, 1951. Vase and bowl decorated internally in diagonal patterns on transparent amethyst and opaque white. Vienna, Museum of Applied Arts.

Vase and bowl amethyst and white, 1951. Vase and bowl decorated intemally with twisted amethyst and white bands of glass. Vienna, Museum of Arte Applicata.

Let’s stay in the United States and go up to the Corning Museum of Glass. Here are some pieces by Archimede including a very original table dated 1950. It consists of an oval shaped transparent glass top resting on legs that intertwine and split in colours ranging from red to green, veined with goldleaf. This table is part of a very limited series which was displayed at the “Art of Living Today” exhibit in Kyoto (1966). At the Corning museum there is also a duck from the early ‘forties in a soft shade of green. It is one of Archimede’s historic pieces which, early in his career (in the late ‘twenties) earned him the title of “master of animals”. In Dusseldorf’s Kunst museum there is a festooned piece dated 1954: a transparent vase decorated internally with festoons of diagonal white and amethyst threads. Something light that shimmers in the air with a rhythm that crosses in the transparencies.

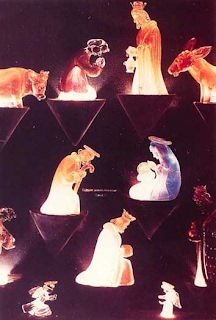

Nativity, 1950. Twelve pieces in blown and stained glass with gold touches. Madrid, Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas.

Just as a note of interest: similar items from this period have come up on the market and at auctions for rather high quotes. The “Nativity” (1950-52) is in the Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas de Madrid in Spain. The twelve pieces, including the ox and the donkey, are made of coloured and blown glass with delicate touches of gold. There is a parallel piece to this: another “Nativity” dated 1966 on permanent display in the Venetian church of Santo Stefano, with masterpieces by Tintoretto and Bartolomeo Vivarini.

In the Art Museum of Vienna, Archimede Seguso is present with two glass pieces of the ‘fifties; a bowl with white feathers and a vase with an irregular decoration of white rows of ribbons. We could go on to mention Archimede’s works on exhibit in the Museum of Venetian Art at Otaru (Japan). Here too, like the vase in the Metropolitan Museum, the acquisition was made after a high level exhibit held in 1990. It was a one-man anthological show of Archimede Seguso’s works: 74 pieces starting from 1932. It is significant to note that the Museum selected some recent pieces as well for its permanent exhibit, proof that his quality has not decreased with the passing of time. And above all, the Otaru exhibit was followed by the great show at the Doge’s Palace in Venice just a few months later, where 180 masterpieces have been presented: almost a century of the history of glass Muranese.

Temple of Muses? Place of Eternity? Words after all seem rhetoric. In any case Archimede Seguso has given something that has wings to fly over the sea of time. His pieces are there, they reflect a light, the light of that which is true beauty: precisely classical, universal beauty.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

GLASS ON DISPLAY

The Biennale of 1972 and the “rigor” of Archimede Seguso. In the year of restoration and optical fashion, the maestro shows Murano glass pieces with a herringbone and petal-like pattern, subtle watermarks in the backlight. At a time of political and cultural disorientation Archimede travels the road to a high formal rigor.

Vase, herringbone pattern, 1972. Cylindrical vase decorated with transparent smokey gray glass with threads of milky straw motif. Base gray glass. h. 27 cm., 8 cm diameter.

It is said that artists – real artists – have antennae. They pick up the signs of the times: they receive, assimilate and interpret. Archimede Seguso’s 1972 story is a fine example: and that is why it is worth dwelling on a bit. And since it is a piece of history, this second issue of “Quaderni” will retell it. What we will see, at the end, is an artist who “felt” his era and gave us his view of it with extraordinary creative and reactive ability.

One “moment” is all we need to focus on: the Biennale exhibition that opened in Venice in June 1972. Archimede was exhibiting in the detached area of the “Ateneo San Basso” in St. Mark’s Square, a few “herringbone pattern” and “petalled” pieces of filigree glass.

He was showing alongside of other artists of the so-called decorative arts (mostly glass and pottery) according to a custom dating from the ‘thirties and which was unfortunately abolished. At the time Archimede’s works struck the viewer because of their shapes: absolutely geometric shapes marked by thin, milky white “straw” motifs. It was glass that we now define as optical, parallel, elegant and fine, in a style that was spreading from the arts to aesthetic custom.

We should take a closer look at the year. Nineteen sixty-eight seemed far off, but it had left its mark. After the (more or less authentic) revolutionary tumult that characterized the 1968 edition of the show, 1970 was a difficult

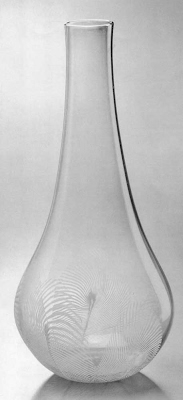

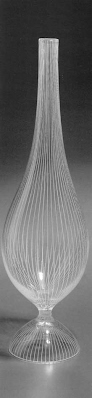

Petal Vase, 1972. Vase, elongated teardrop shaped gray transparent glass decorated

Internally, at the base, five petals pattern of white line motif. h. 35cm., I. 16 cm.

Vase filament, 1962. Teardrop-shaped vase with thin neck and long and clear glass domed foot decorated intemally with continuous vertical white lines of milky glass. h. 45 cm., I. 13 cm. Murano Glass Museum.

moment of transition indeed. The last Grand Prizes had been given to Nicholas Schoffer and Bridget Riley, of France and England, respectively. It was the triumph of Op Art with its linear distortions that had centered on the perception of pure optical phenomena. Then, as the fashions of ‘sixty-eight (and the hypocrisy of fashion) demanded, no more Prizes.

The Biennale was about to “enjoy” a new “democratic and antifascist” charter (today it is deplored as demagogic). Umbro Apollonio had “designed” the 1970 edition of the show in an emphatically avant-garde manner, along the lines of optical and perceptionistic geometries. And then, creeping in, came the restoration.

The “power sharing” politics of 1972 brought a “median” politician such as Mario Penelope to the helm. The theme was ambitious “Opera e Comportamento” (Work and Behaviour). It was supposed to indicate two lines of action in art at the time: on the one hand a return to manual skill, and on the other an escape to a conceptual Utopia. It was a mediocre show, full of compromises and enlivened only by a few resounding episodes: such as the victim of Down’s Syndrome with a sign around his neck, reading: “second solution of immortality: the universe is immobile” (and the author of this happening was Gino De Dominicis).

Nothing could he farther from the classical absolutism of Archimede Seguso’s glass pieces. Perhaps only after years (and a quarter of a century has gone by) can we measure an artist’s distance from historical events. In that period of confusion, discomfort and disorientation that characterized not only art, but the entire cultural scene in Italy (and the general political situation as well), Seguso showed the way to high, formal rigor. Yes, he was living in his own era: the closeness of the Op Art perceptive phenomena was clear, but his attempt to detach himself from the trivial fashion contingent in order to strive for the absolute nature of the artistic creation was also just as clear.

Vase and bowl, herringbone pattern, 1972. Round and cylindrical vase and bowl of transparent smokey glass, decorated internally with milky herringbone pattern, smokey gray solid glass base. Bowl, h. 11 cm., diameter 21 cm.; Vase, h. 31 cm., diameter 14 cm.

Pair of vases, petal motif, 1972. Vases in gray transparent glass decorated intemally, at the base a milky petal motif.

And this shouldn’t be taken as an exaggeration: it is enough to remember the optical wave in clothing and styles in general during those years. Seguso interpreted them in his way, and approached the virtual overlapping of bands of lines that Bridget Riley used (an artist whose perceptivist rigor was truly striking) but at the same time going back to a golden measure which – and we repeat – could not be anything but classic and beyond fashions. Today, in the museum on the island of Murano that houses Archimede Seguso’s works, we can revisit those same pieces from the Biennale with great interest.

We can recognize the mark of the era, but above all, we can see his own mark: the sign of Archimede’s independent creations. Much earlier the master had played that risky and technically

Clear glass vase, herringbone patern-base is gray solid glass, 1972.

demanding card – “merletto”, lace – around 1950. Then a few years later he invented the “plume” (feathers). It was a way of staying close to the intrinsic lightness and transparency of glass. In 1972 those herringbone pattern and petalled pieces were nothing more than the continuation and renewal of a long road, even if they seemed to differ from the main theme of his production.

We can hold those vases and “read” them, perhaps against the light, turning them so that the bands of lines criss-cross in the optical mode and an enchanted filigree where white plays on white, creating superb effects and extraordinary artistic suggestion.

It is a moment of purity, linked to the perfection of geometry. It is a moment that significantly offsets the chaos of a historical period which Archimede Seguso, like all true artists, lived through with a lump in his throat.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

The dining room. On the table, various objects in glass by Archimede Seguso are arranged. The elegant chandelier is too by the master of Murano.

GLASS HOUSE

In a fifteenth-century Venetian home, including antiques, fine ceramics, silver, fine rugs and exquisite furnishings, Archimede Seguso’s glass pieces fit in quite well.

A fifteenth century Venetian house: Gothic facade, typical central hall with rooms opening off to the sides. Fully and remarkably restored, with utmost respect for the essence of the upper middle class home, it emanates Venetian feeling, and the view of “Le Zattere” on the “Canale della Giudecca” is really stupendous.

The furnishings reflect a typically nineteenth century taste for yesterday’s things: antique furniture, little tables, shelves with dozens of knick-knacks collected on countless trips, magical cabinets, fine pottery, silver and fine ancient rugs.

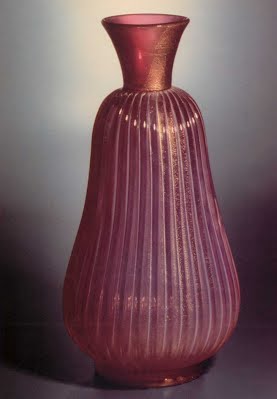

The interior of the room where Archimede Seguso’s pieces blend harmoniously with the refined antique furniture. Featured, series of pink opal vases, circa 1955.

The walls are in a soft warm pastel, the sconces made of Murano glass touched with gold, the beams on the ceiling (which isn’t too high) allow us to catch a glimpse of the antique decorations.

The host wanted the guests to enjoy his home.

Well… and what about Archimede Seguso’s glass creations?

Yes, they are here.

In the grand hall, a triptych of two vases and a bowl, opaline with gold, from the ‘fifties that he seems to have blown in a single breath, and on a nineteenth century table, a Carnival vase from

The studio of “pawn de casa” autoracing champion and hunter enthusiast are shown, on top of the gun cabinet are three cobalt blue ducks (the prototype is from 1935-1937).

Costcontroluce seems of an unreal apparition. Above, the gameroom: chandelier of alabaster glass with bright opache colors for the tulips.

the ‘eighties, where the colours model the shape. And more, on a bureau, “bombonnieres” in lacey glass, typical of Archimede, two cobalt blue flowers.

It’s almost dusk, and I enter the dining room. It is a triumph of glass. On the table: glasses, candlesticks, the vase, small decorations and the chandelier that harmoniously blend with the rest of the furnishings. It was all arranged by the owner of the house, Cecilia Pasotto Dolcetti, and I ask her about this love for glass art and creations by Archimede Seguso in particular.

She answers in a kind tone of voice, unhesitatingly, as if she had thought it over for a long time: “I love glass because I am Venetian, and as such I feel its lightness and harmonious glow.

I love Archimede Seguso’s glass creations because, in spite of being light they give me an impression of matter, that is of an object which is substantial. And I like to surround myself with things I can touch, and hold and caress”.

The intimacy of the bedroom seems almost to be protected by the antique leaded glass of the Venetian windows. And with the dark, the gold of the lights of Archimede Seguso come alive. Back cover, Opal Vase 1955.

Bell shaped Vase with ribbing of shaded pink and gold opaline glass, cylindrical neck with smooth transparent widened ruby lips in gold, base of crystal and gold. H. 42 cm., 1.21 cm. 42 cm., 1.21 cm.