NOTEBOOK 3

Here is an old picture of Archimede Seguso taken on July 11, 1936 at the old Seguso glassworks at Ponte Vivarini, Murano. As of 1946, the firm “Archimede Seguso” would be located at Fondamenta Serenella, 18. This picture is the ideal follow-up to the one taken in 1926 that was published in the previous issue of “Quaderni”. Archimede is standing, second from the left, in front of the furnace, holding his glassblower’s pipe. Born into a family of Venetian glassmakers in 1909, Archimede Seguso is one of the glories of Italian glassmaking art. The fruits of his skilled hands and imagination are in great demand throughout the world and can be found in prestigious collections and museums. An extraordinary technical innovator, Archimede launched new styles and typologies, but above all, he is a great artist. His works, which are real glass sculptures, bear witness to an always fertile relationship with the culture of the times.

PRESENTATION

AN INVITATION TO REFLECT

This is the third stage in the adventure of the “Quaderni di Archimede”. It is an exploratory trip that also has a provocative purpose: the sign – as we have said – of a “culture in motion”, beyond the actual beauty of the items presented.

The items that this great master glassmaker from Murano has been making since the ‘thirties are slivers and bits of our era. They are the symbol of something that is never static, but follows the symptoms of our culture and in the broad sense of our society. Therefore, we are dealing with an invitation to think about something that goes beyond beauty, beyond the external paradigmatic fragility of glass; the feeling that art has succeeded in penetrating the problems of our day.

This third “quaderno” or notebook follows the scheme of the previous issues but it has an “extra”, a motive that unites the texts, the fact that “Archimede Seguso” is in Florence with an exhibition, that will be held throughout September, opposite Palazzo Strozzi in Via Tornabuoni.

This exhibition will feature a “thoughtful” collection of Archimede Seguso’s glass pieces, focused on three aspects that comprise the essence of this “notebook”. There is the fully set table, an occasion for an imaginative combination of stylistically different pieces that are linked by a certain high level “line”; there is the essentially symbolic evocation of Archimede Seguso’s participation in three historic glass sculpture exhibits at Liege and there is the return, with new offerings of that cycle of “rotture” (breaks) that has enjoyed enormous success first at Treviso and then in Venice.

The articles develop along these three main lines, and once again we are witness to a reconciliation, as it were of a great tradition and the future which lies ahead of us all.

CULTURAL NEWS

TABLES OF ARCHIMEDE

The dinner tables of Archimede Seguso will be on display in Florence for the entire month of September. The predominance for decorative motifs and the sumptuousness of the Venetian Renaissance live again, “revisited”, in the splendor of Murano glass created by the great muranese master.

Paolo Rizzi

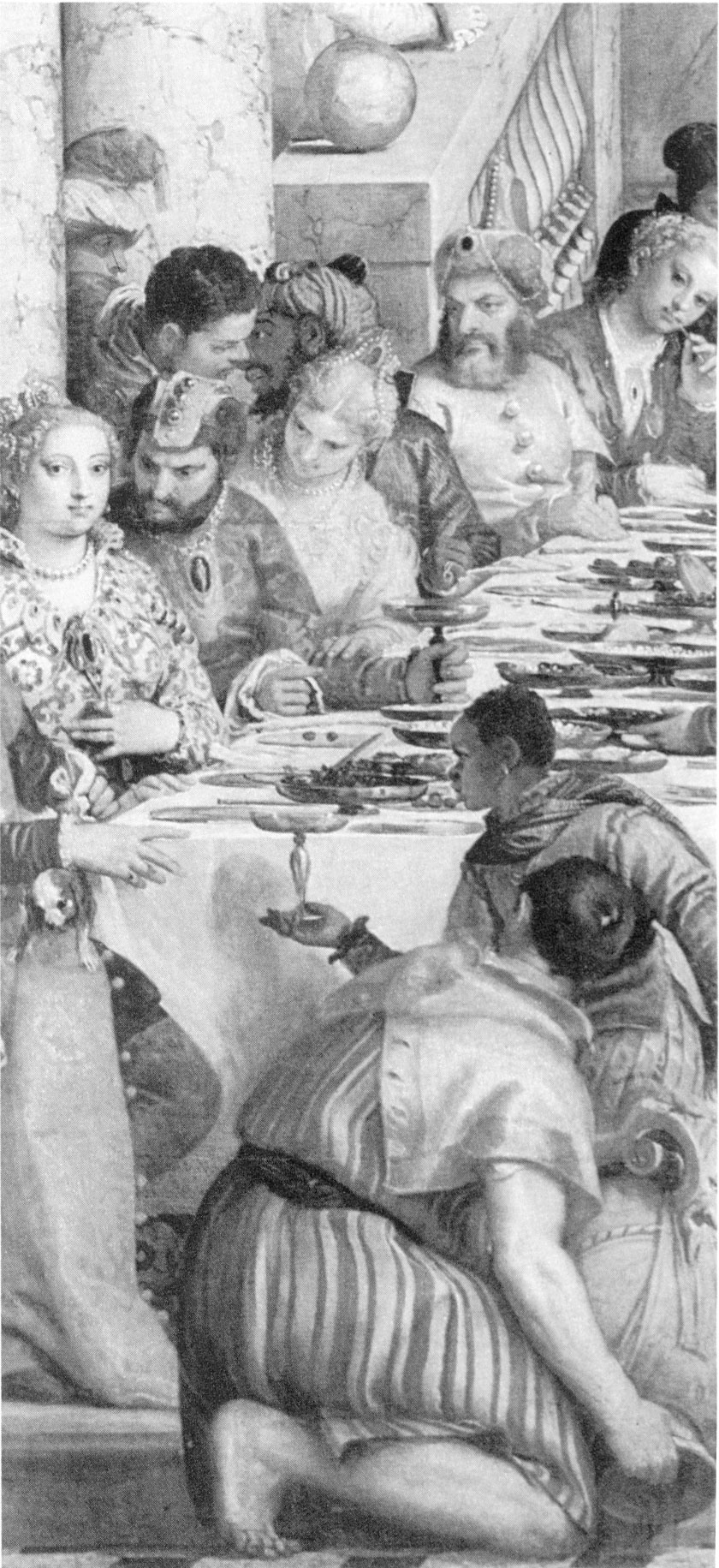

Paolo Veronese was brought before the Court of the Inquisition in Venice on April 20, 1573. He was accused of having painted a Last Supper that was too lavish, with a richly set table, and extravagant characters. The picture seemed inappropriate. The Inquisitor hammered away at the painter with questions:

-Why did you paint that character dressed like a clown, holding a parrot?

-As a decoration.

-And who is at Christ’s table?

-The twelve Apostles.

-What is Saint Peter, the first one, doing?

-He is cutting the lamb to hand down to the other end of the table.

-And tell us, what is the other one near him doing?

-He is holding a plate so that he can take what Saint Peter will give him.

-And the other one next to him?

-He is picking at his teeth.

-Who do you really believe was at that Supper?

-I believe that there was Christ and his Apostles. But if there is space left on the canvas, I decorate it with figures. And the questioning continued stringently.

-Do you think it proper to paint clowns, drunks, Germans, fighters, dwarfs and similar obscenities in a picture of the Lord’s last supper?

-No sir.

-Then why have you painted them?

-I did it because I supposed that they were not in the room where the Supper was held…

And here the most salient remark from the whole interrogation that came spontaneously from Veronese’s mouth:

– We painters take the same liberties as poets and madmen.

As if to say that art goes beyond the “convenience”. It is based mainly on imagination.

Of modern design, the sturdy dishes with curvy edges are put next to buckets, with rings on the sides, of eighteenth century taste and a jar of the 50s of clear ribbed glass with two gold leaves.

All Venetian painting reflects this. It transfigures the object, sublimates it and renders it fascinatingly illusive. All the great Venetian Renaissance painters excelled at depicting the fragile transparency of glass with touches and reflections of colour: from Titian to Tintoretto, from Bassano to Veronese. Later, especially during the seventeenth century in Holland, this exquisitely illusionistic trait would be picked up again in the splendid still-lifes where the strangest glass and most transparent bowls glimmer and shine.

That is why Paolo Veronese so frequently portrayed fabulous banquets with lavishly set tables, fine china, damask and brocades, embroidered linens and elegant glasses. The subject could be religious, like in the “Wedding at Cana” where we see many gentlemen with raised goblets while servants are pouring wine from large jugs, or like in the “Last Supper” that was painted many times, but even religious allegories were coloured with the “taste for good living”: an escape towards a sublime ideal of beauty. And so we have Saint Peter carving the lamb and another apostle cleaning his teeth with a fork. And everyone is dining lavishly… In the end even the severe Inquisition realized the reasons of art, and Paolo was merely sentenced to make a few minor changes in the painting.

When we look at Veronese’s huge banquet paintings today (from the enormous painting in the Louvre to the grandiose “Feast in the House of Levi” in Venice), we discover that the cult of quality of life was natural to sixteenth century Venetian nobility. The china is always splendid, the glassware from Murano always the finest and the linens richly embroidered. The Venetians already adored using cutlery and were ahead of many European royal houses. It is also understandable how Archimede Seguso would be inspired by the typically Venetian tradition right from the beginning. On several occasions he went beyond classic drinking glasses, bottles and vases creating an overall image of the entire table. In fact, some typical items are the center pieces, floral decorations, and large bowls, true sculptures created to decorate the table. It is the same taste that Veronese displayed, that of making things that were considered mere accessories – if not totally

Paolo Veronese “The Wedding at Cana”, detail, Paris, Louvre Museum.

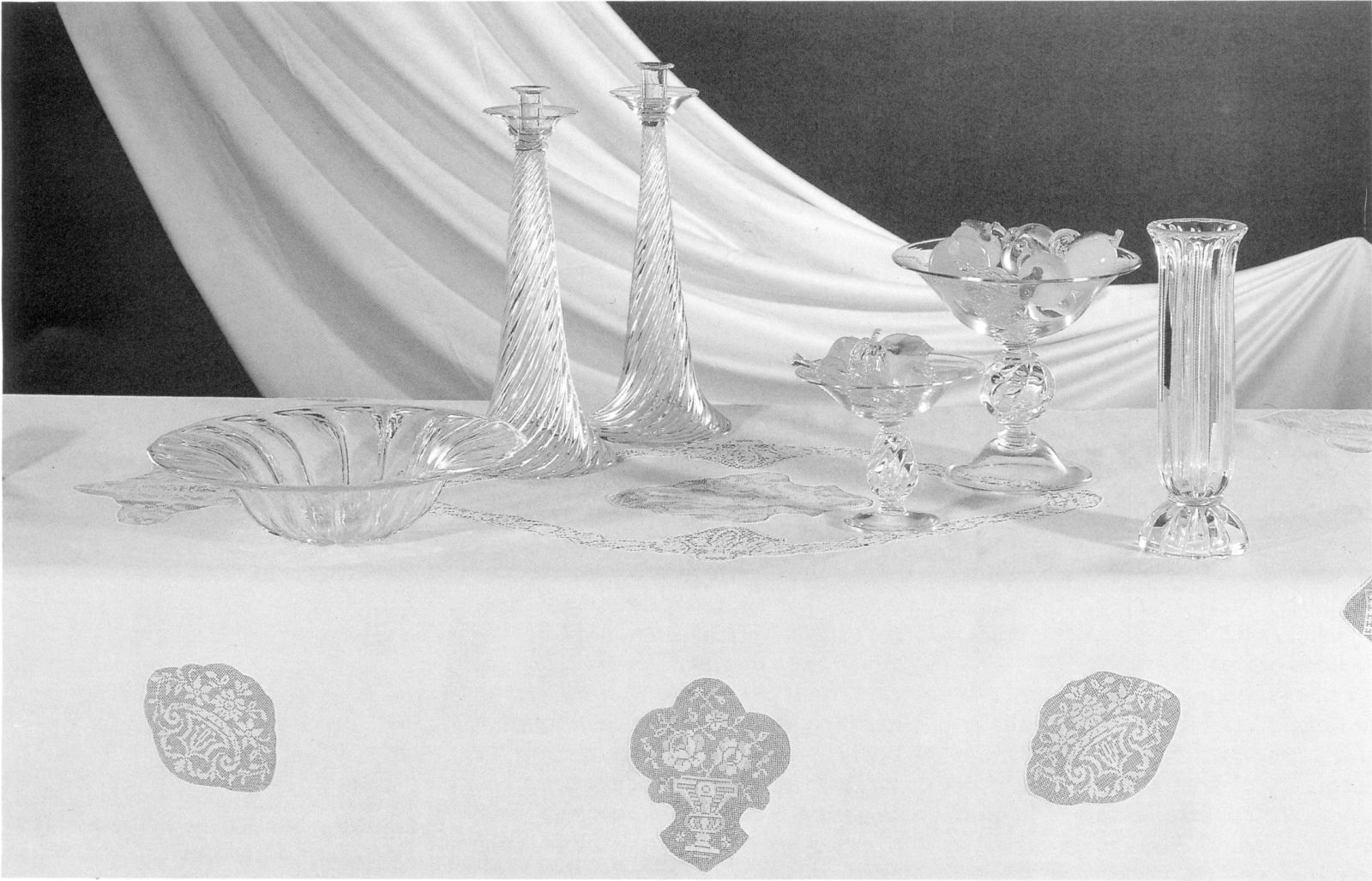

Featured, elegant wine glasses in Murano glass.

useless – important. “If there is space left on the canvas… I decorate it…”, said Paolo Veronese. Decorating the table is a sign of civilization that Archimede Seguso has fully grasped. His tables have become famous for the good taste that inspired them. What strikes us first is the cultural verve that dominates these sculptural and pictorial compositions. These are not adaptations to “a style”, rather highly refined takeovers as we see in the finest art today. Takeovers, that is combinations (made with intelligence and sensitivity) of different modes. So with great amazement we can see combinations that Archimede’s great Venetian taste renders completely plausible. We are struck by certain sturdy plates, sculpted modern four leaf clovers close to delicate buckets that recall the grandeur of eighteenth century Venice. Sitting at a table like this, straddling two centuries, can be exciting. We also see elegant stands with a fascinating cobalt blue dolphin that counter balance blossom-shaped trophies; or a series of airy glasses threaded with gold in the ballotton technique alongside of authentic rarities like the flowers from 1948. And what should we say about the red Veronese vases with goblets decorated in gold and enamel? We also find a striking milky coated decoration on simple, elegant glasses, and we must, of course, stop and look at the caraffes from the ‘forties in gold-trimmed crystal. It seems as if slices of coloured light were floating on the table, golden reflections, sudden sparkles, games of Fata Morgana. And then when ruby red wine is poured into the glasses, these “nuptials” will be perfect.

Elegant table in which the reflections of the crystal are excited by the ribbing of the objects. The glass blown candleholders are accompanied by a bowl and vase and stands with assorted fruits of opaque and transparent colors.

Naturally, this fragile yet eternal beauty of glass is presented on the most stunning embroidered linens. Archimede could have chosen no better frame for his glassworks. Already in the ‘fifties he felt the charm of the refined levity of the embroidery so much to create impalpable glass tissues as his famous vases “Merletto”. Here, the linen drawnwork (lilly stitch) table cloths, or at Venetian lace, or with filet inlays, are exalted by ethereal blown glass transparencies, joining an unique art. Once again two worlds meet and co-exist. Defending himself against the inquisition, Paolo Veronese put art’s reasons first. Beauty is not only a hedonistic fact, pleasure of the senses. It is the sign of an inner balance that leads to that “quality of life” to which even a splendidly set table can give access. And looking at the glasses sparkling in the “Feast in the House of Levi” we can see that something of the Venetian taste has picked up the ancient threads and woven them into today’s multicultural scene with exquisite grace and imagination.

A table set with soft warm tones and gold shadings, where tall candleholders tower.. Linear dishes are served with sprinkled gold glasses worked “ballotton” with dolphins and lightweight crystal glasses. A jug and precious flowers made in the late ’40s complete the table setting.

LOOKING BACK

SCULPTING IN HISTORY

The beautiful sculptures on display at the Triennial of Liège, 1986, 1989 and 1992, testify to the artist’s painful participation in the political and cultural events of our times. Expressions of technical skill and creativity that translates into a universal message.

“My Europe”, 1992, blown cobalt blue glass obelisk supported by four spheres on a cubic base, crystal stars. h cm. 2 J J.

It has been said that the artist has antennae. That he can grasp society’s premonitions, symptoms and states of mind. He absorbs and translates, interprets and symbolizes. Even in the space of a few years, he assimilates everything that transpires around him. This is true of Archimede Seguso. Even his glass creations reflect the world and its changes. Perhaps, at the time no one really notices, but let a few years go by and suddenly the relationships, agreements and interactions are all visible.

The example of the European Triennal Exhibition of Glass Sculpture at Liege is typical. Archimede Seguso participated, upon invitation, in all three editions: 1986, 1989 and 1992, organized by Joseph Philippe and Generale de Banque, who also edited the catalogue.

Today, looking at the pieces he exhibited then, we can see the reflections of the era in which they were made. It’s curious, strange. Beauty, even when it attains moments of apparent abstraction, that esthetic sublimation, conserves the germs of the situation, (existential, psychological, cultural and even political in the broad sense) from which it was born. Archimede’s glass pieces can be represented that way, and we believe that this interpretation is more than justified.

1986: the international situation, due to the conflict in the East, was scalding. The five beautiful pieces that Archimede showed at the first Triennal at Liege bear witness to a generalized concern; the most impressive example is a piece entitled “Millenovecentottantasei” (Nineteeneightysix) representing an Oriental man’s head from which the cylindrical shapes of missiles seem to be flying out. It’s an impressive sculpture precisely because it turns the unreal beauty of a glass into a piercing expression, cruel symbolism against a surreal background. “Thoughts explode in the civilization of chaos”, is what Archimede said at the time.

Even the other four pieces exhibited at Liege reflect a bitter unrest, even if the artist always maintains the vital flow of nature. And so, here is the splendid “Germoglio” (Sprout) where we see a violent “desire for life” shooting forth from the spiked black plant; or “Controvento” (Against the wind) where the artist rejects the black clouds of the present and lets himself be carried on a gentle wind of a future portrayed by a splendid head with flowing hair. The current tragedy is offset by hope.

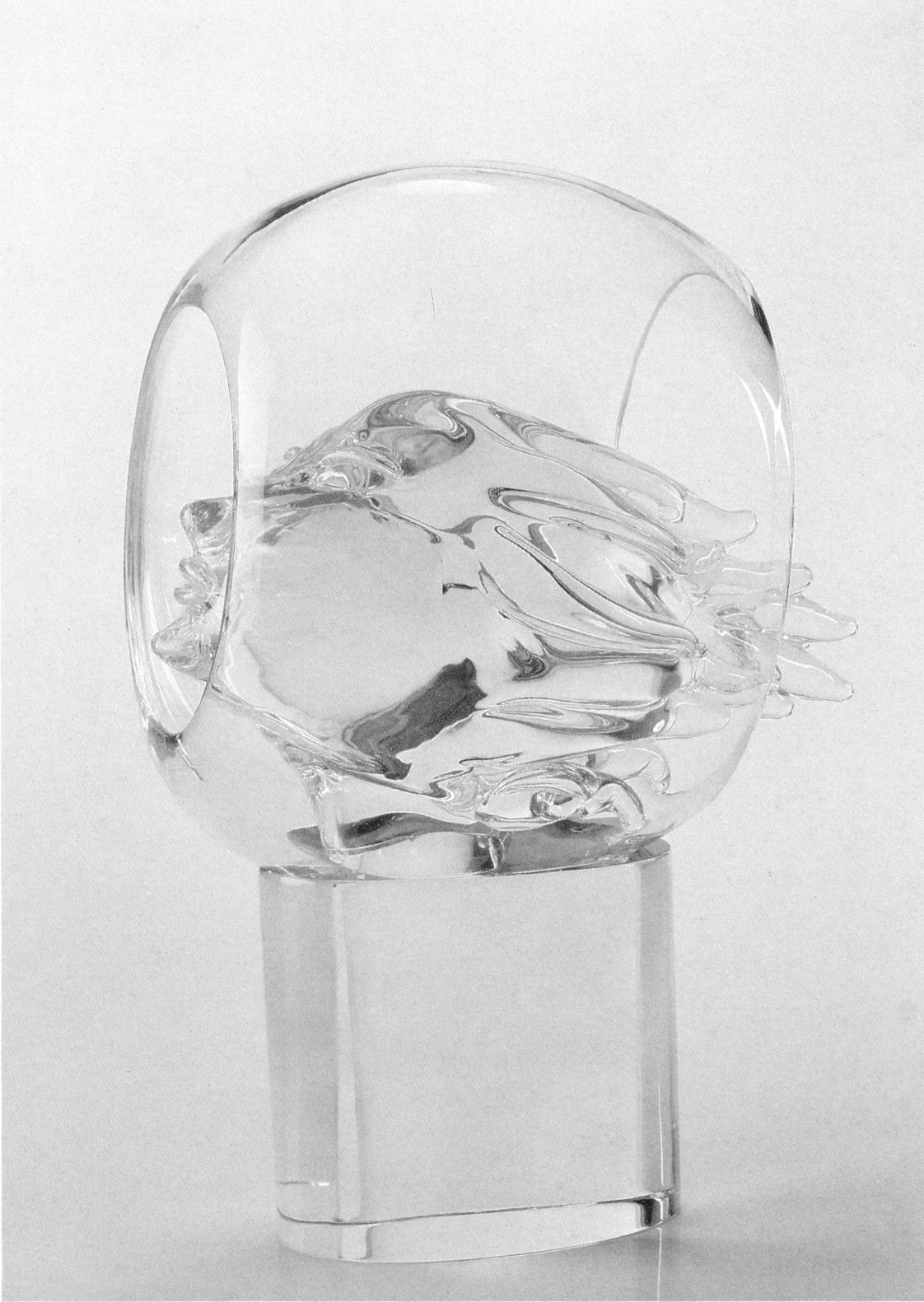

Image, 1986, crystal glass sculpture on a black base. The sensitivity in the woman’s face becomes subjective contours. cm. 45 x 29 x 32 h.

1989: the problem facing humanity is that of liberation. Racial conflicts became fiercer. “Astronauta”, an extremely complex solid and blown glass sculpture bringing us a human face encased in a sort of space suit from which it seeks release. The concept is clear: a vital core that has difficulty accepting the physical and psychological barriers that compress it. The result is a powerful piece combining compression and release in a desire for freedom. “Lassù” (Up there) is also part of the same category: another solid glass sculpture projects upwards and towards the infinite.

Archimede feels the theme of freedom with a great civil passion. But he carries it over into a universal sphere, so that his works reflect the contemporary in terms of esthetics, but sublimate it in the purity of metaphor.

“Astronaut”, 1989, sculpture in solid and blown puff on a glass “crystal” base. The dynamics in the space constraint of staying alive. h cm. 39 x 29 x 19.

Titled “1986”, 1986, crystal glass sculpture. My thoughts exploding in civilization and chaos. cm. 32 x28 x48h.

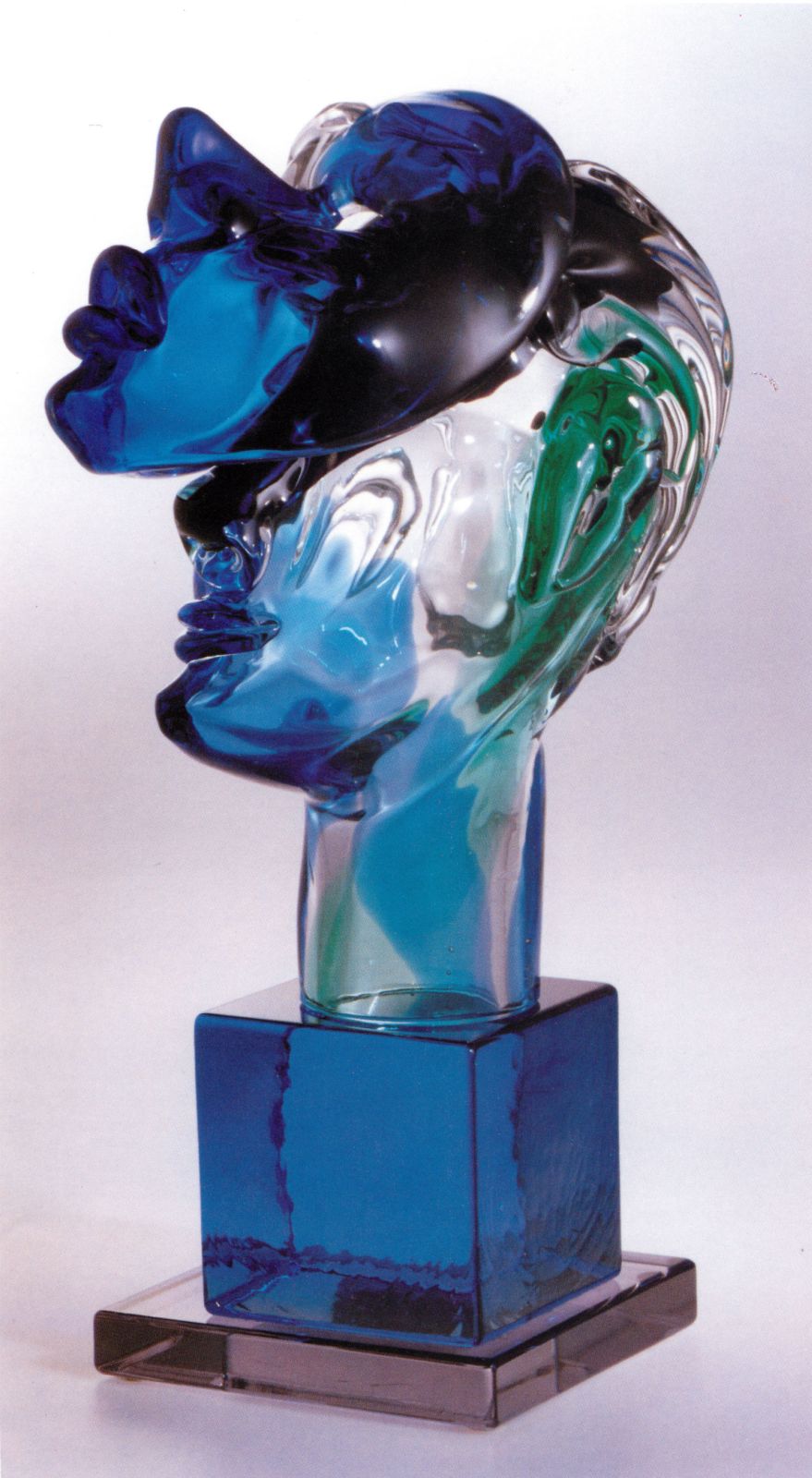

1992: from the issue of race to an opening for solidarity among peoples. Two works are sufficient to understand how the contrasts can be overcome. “Incertezza” (Uncertainty) shows a face, half-covered by a mask. The cobalt blue, as deep as the sea is infiltrated by a tragic black: the symbol of uncertainty, hardship and conflict caused by a situation that embitters the artist. Faith in tomorrow comes from a huge cobalt blue blown glass sculpture. It is an obelisk of “bricks”, 2,35 meters high, supported by spheres on a cubic base and topped by twelve golden stars. The title is simple: “La mia Europa” (My Europe).

The obelisk, by itself conveys the idea of a solidity which seems to challenge time by pointing upwards. A sign of solidarity and compactness, practically a visualized concept of a Utopia the artist definitely plans on reaching. Reading through the alchemistry of Beauty: this is the call we get from the art of the great master Archimede Seguso. There is no material more suitable than glass, with its transparency, for visualizing an idea which takes off from the artist’s sensitive-intellectual core like a universal message. And the triennial exhibitions at Liege are definite proof of this.

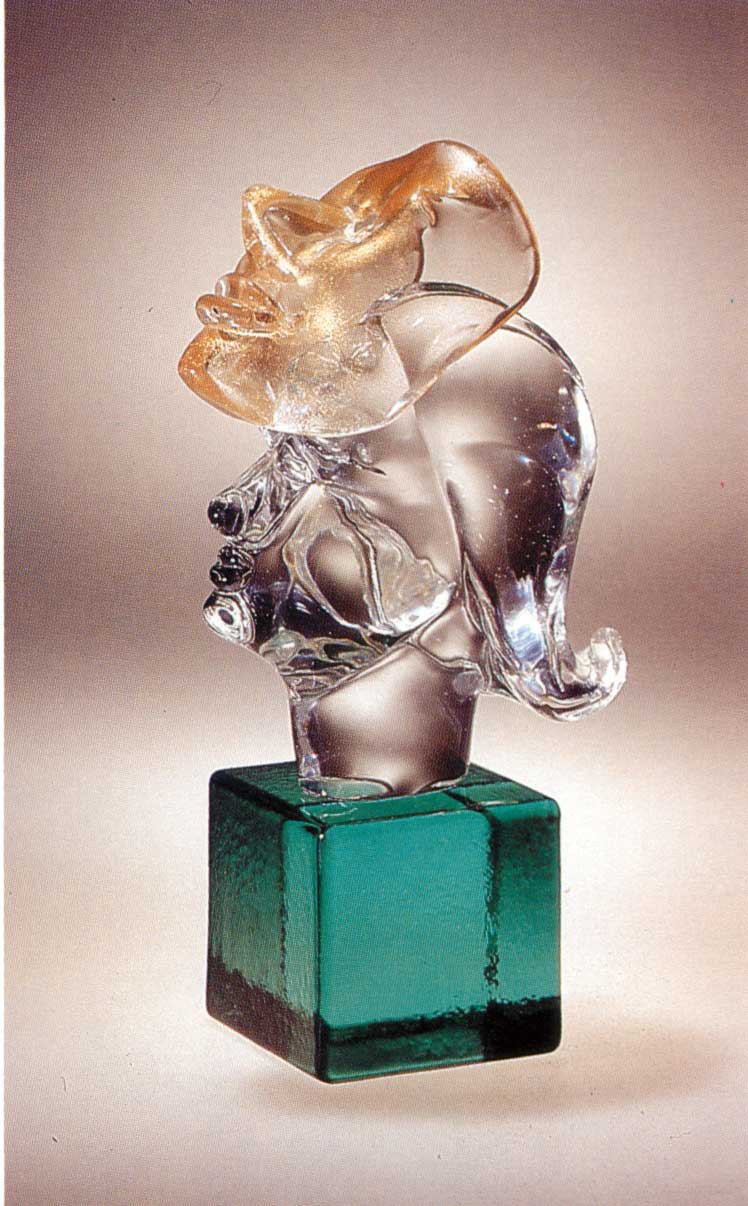

“Uncertainty”, 1992, blown glass sculpture with blue and green spots . On the cobalt blue mask the black shadow is reflected. cm. 48 h. Above: French Sailor, “Matelot”, 1992, blown glass sculpture with green blue spots and cobalt blue hat. The second base, in a more intense blue, is reminiscent of the undertow. cm. 37 h. Below: “Columbine”, 1992, head of a woman in crystal with gold crystal mask on a light green base. cm. 33 h.

“Germoglio”, 1986, a woman’s face in clear glass that comes from a bunch of spear-shaped leaves edged in black on a black base. h 40 cm. x 40.

“Controvento”, 1986, crystal glass sculpture. The wind, like life, serenely into the future. cm. 30 x 10 x 30 h.

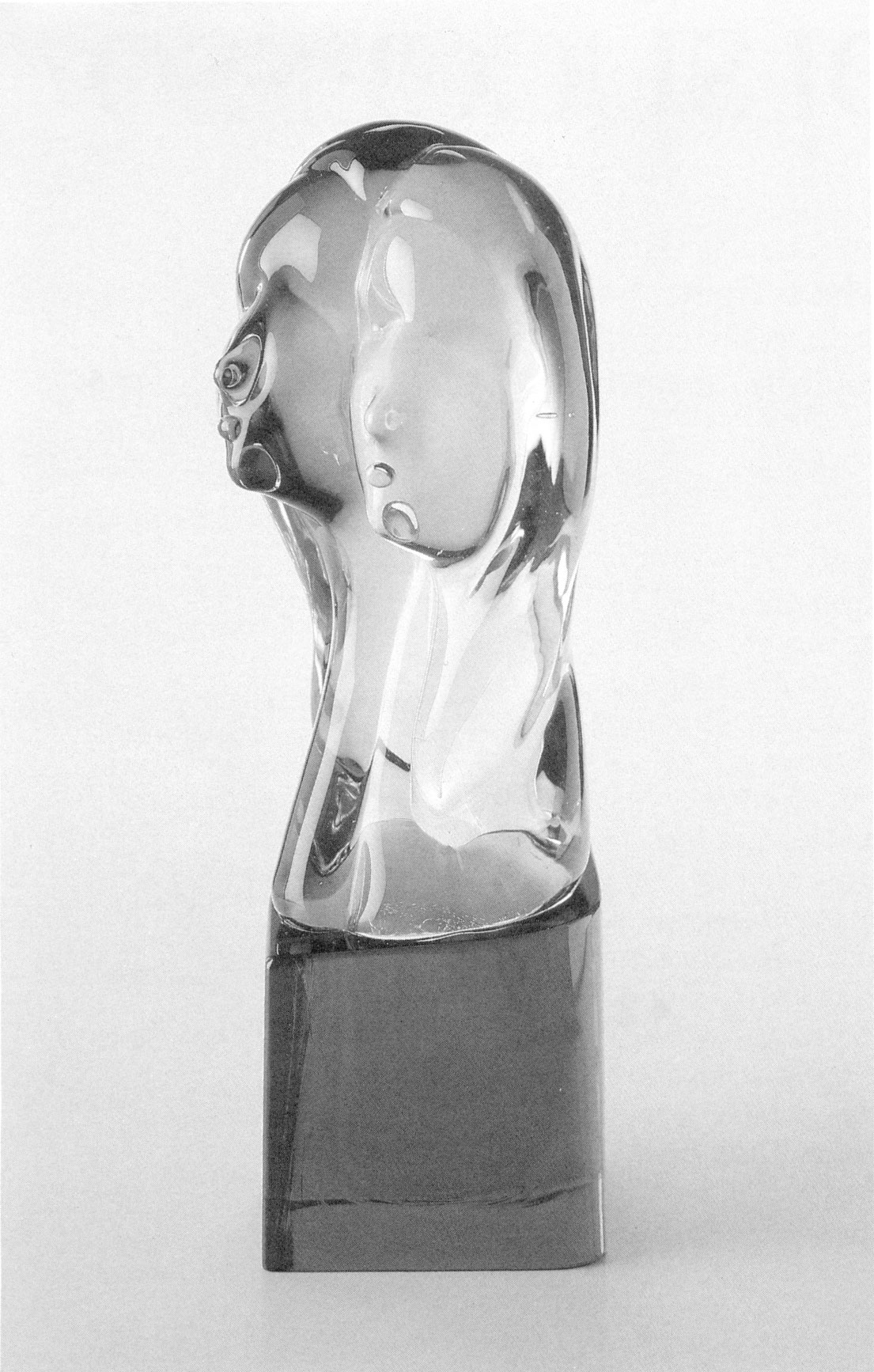

“Profile”, 1989, sculpture in solid glass “crystal”, shaded in cobalt blue and emerald green. h cm. 39 x 14 x 16.

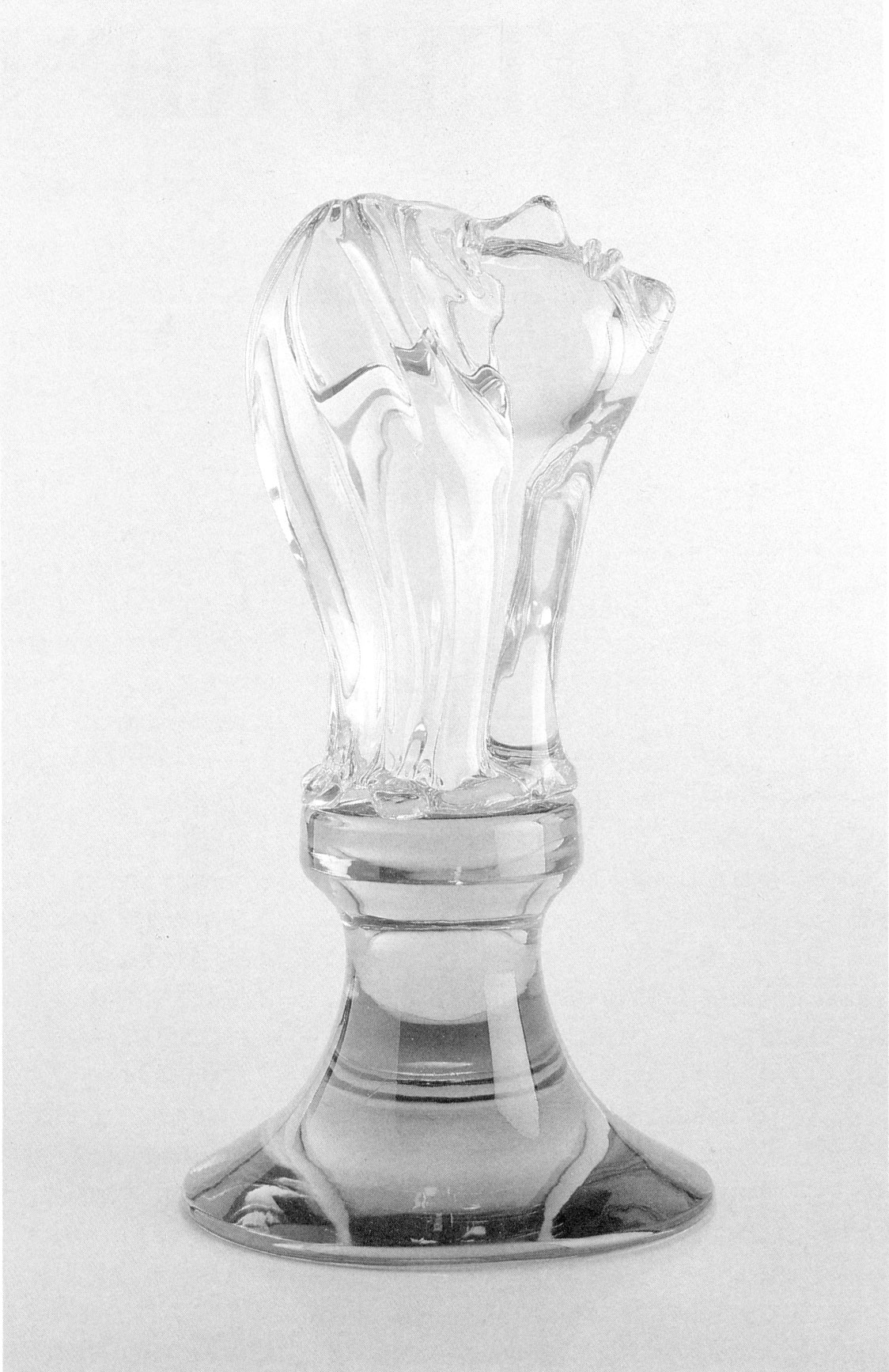

“Up there”, 1989, sculpture in solid glass “crystal” on a hand-made base in pale green. The projection, the momentum to reach the infinite serenity. h cm. 42 x 23.

“Double Eclipse”, 1986, crystal glass sculpture on a black base. In the days of the renewal of life, the eclipse is a moment that you can not even see. cm. 30 x 26 x 29 h.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

“BROKEN” SUCCESS

Brand new pieces of the ” rotture” cycle came from the hand of master Archimede Seguso. This success is repeated. Splits, tears, tension, a strong drama explodes, and reassembled, in the bright, phantasmagorical sculptures of glass.

The subject “rotture” (breaks) is typical of Archimede Seguso’s latest creations and is very closely tied to the psychological situation of our common eras. We already spoke about them in the first issue of these “Quaderni”. The first exhibit of the “rotture” cycle met with great success in Treviso; then came Venice; this September it will be brought to Florence to be followed by Rome, Milan and abroad starting with Lyon. Critical acclaim matched the public’s enthusiasm. These sculptures were admired for a triple quality: great technical skill; symbolism; and finally intrinsic beauty.

“Movement in tension”. Mass of transparent glass on a black base decorated with blue, green, and scattered dustings. h cm. 30.

“Composed pieces”. Ruby crystal glass disk submerged with cobalt blue insert. h cm. 28.

Here are some of the newest pieces crafted by Archimede Seguso’s magically skilled hands. The theme is the same, “rotture”, or breaks. This time extending to laceration, splitting, explosion and, in response, recomposition (rebuilding) of the shape. The trauma continues; in fact, it becomes even more complex with increasingly unsettling existential nuances that transcend human nature. A crystal disk with bluish shading cracks: on the left we can see the diamond like facets caused by the explosion. Another disk splits in a circular, spiral movement accentuated by a type of lens that magnifies and staggers the planes. Here the break is even more conceptual and is carried over into the spatial dimension of chromatic sparkle (golddust) which creates an alienating effect. There is a virtual movement that gives life to these sculptures making them phantasmagoric and at the same time, delightfully obsessive.

“Emotion dynamics”. Masses overlapping transparent glass with blue decorations, scatted gold dustings. h cm. 43.

The “rotture” cycle, was created last year by this eighty five year old artist from Murano. He made an explicit effort to render the glass even more expressive in the instant that it changes from the liquid to the solid state. The break is fixed in space and time, frozen in a feeling of exasperated beauty. Glass expels a splinter from its own mass, or it explodes violently, or it breaks down until it becomes a galaxy of light, it moves in the pain of a traumatic laceration. Sometimes it spasmodically tends to bring the fragments back together again, forming a brusque dialogue within the shattered mass… This is not a mere play of forms and shapes, nor is it the thrill of dynamic emotions: energy is transformed into spiritual power, and the anguish from which these stupendous glass sculptures are born is translated into a throb of universal dramatic strength.

“Virtual movement”. Masses of transparent glass on a black base with blue decorations, scattered gold dustings. h cm. 30.

Back cover, “Internal tensions”. Masses of transparent glass on a black base decorated with blue, amethyst, green, and scattered gold dustings. h cm. 35.