NOTEBOOK 4

Archimede Seguso in front of his furnace in Murano, Venice. The picture was taken in May of 1994. The artist from Murano went to work at the furnace when he was eleven, in 1920, and from then on he continues to create extraordinary masterpieces of Venetian art form. Archimede’s pieces are in museums and in prestigious collections all over the world; they represent an always new proposal of styles, typologies and techniques.

PRESENTATION

UNINTERRUPTED MAESTRO

The fourth “Quaderno di Archimede Seguso” is dedicated to the exhibit of the master’s works that will be held from January 19 to March 10 in Lyon (France). The show, at the Hall d’Honneur of Credit Lyonnais, sponsored by the Istituto Italiano di Cultura, has been arranged with the cooperation of Gina Giannotti. Old and new pieces highlight the extraordinary and unstoppable creativity of Archimede who has been making masterpieces in glass since the ‘thirties. And these masterpieces have provided an accompaniment to the technical developments in Venetian glassmaking and the history of our country as well. Therefore, this is a tribute to an artist who has proven himself capable of knowing how to create, to anticipate, and interpret the events of this century, and of translating thoughts feelings and emotions into reality. This exhibition presents a “new” opportunity to admire the master’s works. “New” because there has never been any déjà vu in Archimede’s artistic career. Old and current pieces, from the objects of the ‘thirties to those made in 1994; animals, sculptures, filigrees, lace; mirrors, dresser sets, smokers’ sets, centerpieces and candlesticks; the recent “rotture” and “intrichi”; and the nativity scenes. The pictures in the “Quaderno” speak for themselves. They tell the long and gripping story of the glass, talent, skill and experience of a man who has dedicated his entire life to the art of glassmaking. Nearly a century which, even because of its emotional power, represents a compendium of the greatest artistic expression of a thousand years of glassmaking. A book: Archimede Seguso. Maitre Verrier a Murano by Renato Polacco, will be available early in the new year. It is a document on the master’s life and works. Another development in our constantly evolving culture.

CULTURAL NEWS

ARCHIMEDE SEGUSO

A GLASS MASTER IN MURANO

The exhibition in Lyon, from January 19 to March 10, old and new works by the great artist who knew how to translate, in his creations, feelings and tendencies of almost a century of history. Punctual interpreter of a culture in motion.

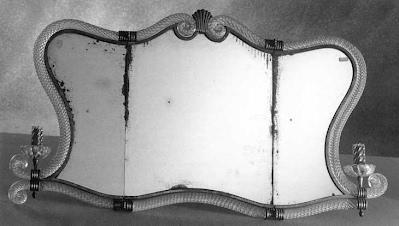

Mirror, 1936, h. 50 cm x I. 41 cm. Mirror with ribbed twisted green glass, decorated on the top with shell and applied in the center, a bouquet of tulips tied with a ribbon.

Archimede’s complex and varied products are subject to constant renewal and are, therefore, a source of constant surprise. When we take a look at the “archives” of his works, we are astounded not only by the quantity, but mainly because his creative strength is so great that it is impossible to select one item that can represent technique and line in any given period. The formal aspect renders the various pieces singular and even “conflicting” because of the specific features that he transfers to each one. The artist’s desire is to attain perfection that goes beyond the techniques and shapes of objects that have even just been created. Therefore, one part of the exhibit is retrospective while another covers recent works. The ‘thirties are represented by a series of works in which we can see Archimede’s precise desire to move away from the “Old Murano” style that other glassmakers continued to favor for purely commercial reasons. Archimede created an artistic image that was totally independent of past events, and consistent with the object’s function and the formal essentiality demanded by the culture that developed as a result of scientific advances and spreading positivism. The triptych mirror with lateral candleholders dated 1937 immediately reveals this desire for the “new” as overlapping a cultural substratum that has strong roots in the antique. The curved lines of the glass edge that frames the triad of mirrors come together in elegant scrolls at the top and sides where the candleholders are situated.

Table mirror, 1937, h cm. 47 x I. cm. 82. Triptych mirror frame with twisted ribbed glass crystal with gold that is wrapped in scrolls and curly at the top and sides where the candleholder is inserted.

It evokes eighteenth and nineteenth century mirrors, but the entire composition emanates Archimede’s new vision of a work of art. A gilded metal edge that outlines the curving edge joins perfectly with the shell “embraced” by the two glass sea urchins. There is a sense of the plastic, a prelude to solid glass sculptures; essential lines and compositions using different materials in a quest for coherency of form. Similar comments may be extended to the 1936 mirror in which the forms Archimede created are translated into an essential and modern key, like the elegant bunch of tulips tied with a flowing ribbon. A master’s hands transformed stereotyped decorative elements that were overused and inflated through the centuries into objects that are an absolute delight combining purity of line and delicate colors.

Fox, solid light green glass, 40s.

This sense of naturalism that attained perfect stylization can be seen in the burnt glass and gold vase that was designed in ’38 and made later. During the same period he made a light green solid glass fox: with its agile and curving lines, it is hard to distinguish the animal from the bushes where he crouches awaiting the message that will make him spring forward. A highly intellectual process preceded this piece, an example of glass sculpture in which Archimede’s art is distinguished from the many items of the same genre made in France.

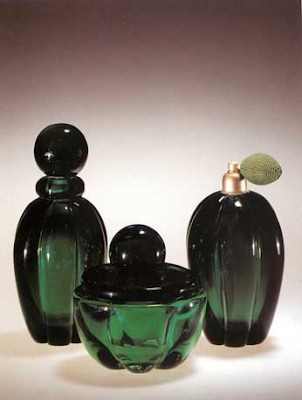

Archimede’s creativity, expression and immediacy are far different from the redundant decorativism of the others, with Oriental-style ingredients that contaminate the poetry of the inspiration behind this Art Nouveau masterpiece. Among Archimede’s pieces from the ‘forties we can see a reflection of the news of a new society in which the cinema became an image to be imitated. And so, Archimede created dresser sets in green glass consisting of perfume bottles, atomizers and powder boxes for the “stars” to do their make-up. The “liqueur sets” with bottles and glasses, and the “smoker’s sets” with ashtrays, cigarette holders and match box holders all became necessary items for home furnishings during that period. The two and three-arm clear glass candlesticks were made in 1948.

There is even an evident trace of ” Old Murano”‘, Archimede reinterpreted these shapes with a new sensitivity: essential simplification of the spiral motif to strengthen luminosity and give them a life of their own. The centerpiece (1950) is interesting for its “modernity”; it is made of crystal-gold glass and consists of a large central bowl supported by four arms with candleholders at the end that can be transformed into cups. The simplification of line and shape carried to the essential corresponds to the setting it was made for: a new, aseptic, American house. The candlesticks, bases and vases in dense ivory glass and gold to create metallic effects are typical of the early ‘fifties (even chandeliers were made by using brass to connect the glass parts, so that the golden metal would blend easily with the golden colors in the glass).

Vase, irregular tree trunk, 1948, h. cm. 40 x I. cm. 22.5. Oval jar with wide neck protruding, blown glass with gold color, rough surface and irregular shape. Built in 1948 from a 1938 design.

And each of these pieces meets the essence and functionality of the object as demanded by these modern aesthetic requirements. The ribbed vases were made of coral and gold glass that supports golden crystal flowers and leaves. The harmony of line and color seem to embody many aspects of Venice and her art. The artist’s search for the absolute form through constant experimentation seems to have been rewarding for Archimede. It allowed him to create new techniques and combinations of materials that border on virtuosity.

Candlesticks, 1948, h. cm. 13 x I. cm. 18.5 h. cm. 19 x I. cm. 27. Two candlesticks in clear ribbed twisted glass, one of which is on a hemispheric ribbed base.

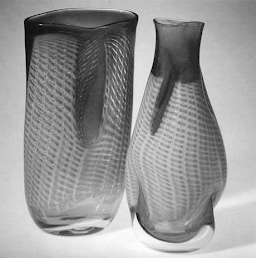

This is the true attitude of any artist facing a material such as glass: its moldability responds to every surge of intelligence. The more alive the creation, the more varied the fades of the glass. The search for new designs, as it were, began in the late ‘forties – early ‘fifties. Two bowls belong to this period: crystal with three stylized spirals in the form of triangles of white threads and the small basin with concentric twists of white “zanfirico”. The elegance of these creations derives from the perfect balance between the base (crystal) and the white filaments that herald the arrival of the lace. This revisitation of the ancient filigree and meshwork technique starts with a thread of opaque white glass.

Centerpiece, 1951, h. cm. 46 x I. cm. 35. Centerpiece glass crystal and gold centerpiece formed by a central bowl supported by four curved arms ending in candleholders which also exchangeable into cups.

Vases, herringbone pattern, 1972, h. cm. 36 x I. cm. 13 h. cm. 26 x I. cm. 12.5 clear glass vase internally decorated with dull yellow wire in a herringbone pattern.

It runs over the entire length of the piece, twisting and turning with helicoidal movements until it has woven a complex, repetitive pattern throughout the glass. Two or three years later, Archimede materialized vibrant “feathers” of colored glass tubes in immobile clear glass: it was a surreal vision suspended in space. Technical mastery is still present in Seguso’s works. In the ‘nineties he created a group of objects in which, once again, the absolute form is supreme.

Dresser sets, 1940. Dresser set composed of perfume bottle (cm. 20.5), atomizer (cm. 14) and powder box (cm. 13) of a ribbed green transparent glass.

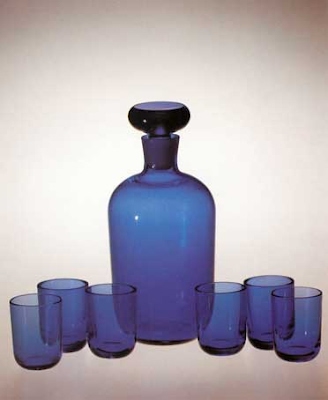

Next, cordial service set, 1940. Cobalt blue glass bottle with stopper in solid glass(cm. 19.5) and six cylindrical glasses (cm. 5,5).

In the “vasi riflessi” (reflected vases) (1990) the artist sets the perfection of form in the harmonious balance between the textured parts and the crystal inlays. In the white-coral “vasi a rete” (mesh vases) the glass receives movement from the extended meshwork surfaces bounded by the clear areas at the base and the thick, contrasting colored ribbons near the mouth. In the two “vasi a raggi” (ray vases) made in 1992 we see glass combined with an adventurine and green starry motif made with a delicacy and elegance that only Archimede could achieve. Each star seems to shine with golden reflections off the transparent diaphragms of the glass, as the eye circles the sparkling surface.

Bimbo, 1972, h. cm. 28 x I. cm. 16. Head of a baby reclining on the shoulder in alexandrite colored glass, on a solid black oval base.

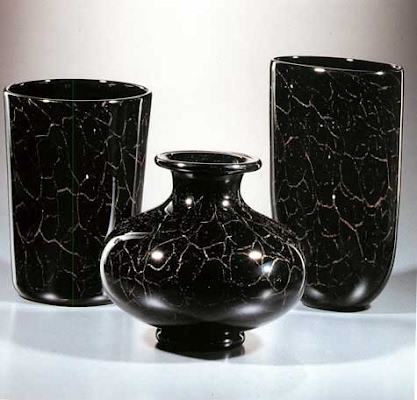

Vases “intrico”, 1994, cm. 31, 5 x 18; cm 27 x 19; cm. 22.5 x 25. Vase with oval section, vase with round section, and oval vase with cylindrical neck and base, of black glass, decorated with interwoven strands of avventurine.

Two other vases from 1993 enrich the documentation on Archimede’s creativity which seems to become inexhaustible as the years go by. The first is a wide-mouthed piece in cobalt glass, wrapped in a “new semi-filigree” of “applique” milky coated sticks or tubes. The other is round with a flared, narrow mouth, decorated with intertwined milky coated overall “weave” of the threads in which the colors combine to create a dull red accentuating the contrast with the crystal background that shows through the tight “mesh”. Even during the final months of ’93 Archimede managed to apply the “Intrico” technique to totally new solutions as documented by three adventurine and black vases. The complex and highly articulated pattern of the adventurine ramifications wraps around the black crystal, sinking into the material to reemerge with a vibrant, luminescent effect which is further enhanced by any light that may strike it.

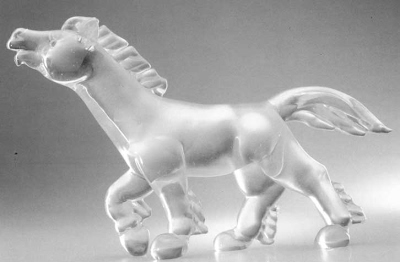

Cavallo, 1950, h. cm. 20 x I. cm. 34. Horse worked in iridescent solid glass block.

Highly elaborate pieces, these, which require decisive and perfect skill in blowing and forging the perfect form, and just as much perfection in creating the pattern. The surprising elegance, composure and harmony of form that have long comprised the artist’s greatest aspiration are evident in the hot glass sculptures, an important area of Archimede’s work. Looking at the melancholy alexandrite “putto” (1973), it is probable that Archimede was thinking of the Guido Reni exhibit in Venice. The sweet face and the full shape is a marked contrast with the strong lines and irony of the grotesque dated 1948. It is a highly refined piece of sculpture in Siamese-ruby red, where the “soft” shape allows light to expand and enhance the gleeful image through the transparency of the material. The gold crystal hand is dated 1993. In the spring of that year, going to work one dawn, Archimede tripped over a board, fell and fractured his hand: one hundred days of idleness. With the help of a young man and much obstinacy, in silence and with great suffering he put his hand back to work.

Masorini, 1951, h. cm. 18, 5 x 15, cm. 20.5 x 10; cm. 23 x 10. A group of three wild ducks of solid glass submerged in a milky coating with gold crystal.

Hand, 1993, cm. 24 x 13. Hand made of solid glass crystal with gold.

Six months later he was able to prove that there was indeed still a direct line that connected the hand to the brain, and he created his hand in glass, strong, agile, but slightly crooked—as a gift for his doctor. Archimede even succeeds in capturing expression in the solid glass animals that are a recurrent theme. In the ‘fifties he created the gilded birds in different “poses”, with shaded plumage: green blue and gold ducks on water in milky coated gilding; ducklings in motion, ducklings standing still. Elegant swans in realistic positions: delicate shaded tones on deep green bases. It is interesting to note how these animals developed in parallel with Seguso’s artistic growth. One example comes from 1965, the year of the horse in Japan. To satisfy requests for that market, Archimede created horses, even drawing on ideas from those he had made in previous years. Still horses, but different as they evolved through a study of motion and the diversification of materials that allowed Seguso to innovate while presenting subjects that he had already done. Chromatic expression is a key element in Archimede’s work.

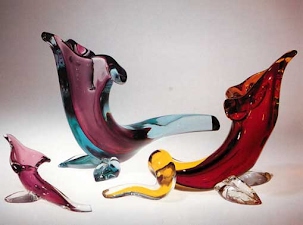

Cornucopia, 1956, h. cm. 53 x 18.5; cm. 23 x 10, cm. 45 x 17.5. Submerged glass cornucopias in ruby aquamarine, ruby crystal, and ruby yellow.

Uccellini, 1949, h. cm.15, 13 cm, cm diameter cup. 8. Birds on crystal clear glass base with gold shaded in green, red and blue. Falling edge bowl with gold and coral shaded glass.

The colored glass mass that comes from the heat of the furnaces is the result of technological and at times empirical research. His feeling for color leads him to anticipate fashion. One fine example is the “sommerso” or submerged technique that makes it possible to achieve intensity of color by overlapping several layers of colored glass. The group of pieces made in 1956-57 with this technique can be called “underwater”, because of the shapes (stylized vases and fish, absurd cornucopias), and for the luminescent effects created by solid pieces of glass wrapped in crystal embedded with colors that range from blue to ruby to lilac.

Pot and cache-pot, coral, 1950, h. cm. 30.5 x I. 21 h. cm. 22 x I. 27. Pot and cache-pot of coral and gold ribbed glass with two gold leaf glass handles.

The alabaster with which the peasants with baskets were made in 1959, in green, is one of the glass types that best fulfilled the figurative needs of the ‘fifties. Its translucent consistency made it possible to create vases and figurines in which the plastic and rounded shapes favored the simplified lines and “pastel” color effects that were popular in the sixth decade. In 1973, the year in which Archimede and his family reorganized the business, also brought about experiments in glass and color. The group of three two-handled and ribbed vases, the green opaline bowl and pitcher belong to one of the small collections also made in “chalcedony” and opaque rose where silver is one of the basic components of the glass mixture. Perfection of shape and harmony combined with the clarity and limpidity of the material are the linguistic constant that has characterized all of Archimede’s production.

Vase-ray, h. cm. 32 x I. cm. 21.5. Oval vase of glass crystal with blue profiled edge, decorated internally with four bands of green avventurine ray weaving.

Bowl-ray, h. cm. 14 x I. cm. 29.5. Oval bowl of crystal glass decorated internally with three bands of green aventurine ray weaving. Looming green ribbons decorating the center and the mouth is slightly protruding.

On the other hand they are also the basic, indispensable factors for the attainment of that “beauty” through which the artist’s feelings or momentary psychological moods are abstracted from the dimension of the “specific” and “personal” to rise to the level of the universal message. Although we do not yet have the full chronological picture that would permit a completely documented criticism, we can somehow feel the psychological processes that led the artist to create the recent “rotture” (breaks).

Vases reflections, 1990, h. cm. 31 x 32 x 17.5 and 15. Vase with oval and irregularly shape, amber glass, decorated in the center by a jagged pattern of transparent amber and opaque white strands.

Bowls, white threads, 1949, cm. 30 x 27; cm. 23.5 x 21. irregularly shaped crystal glass decorated internally with geometric designs of concentric white strands. Zanfirico cup, 1952, cm.18 x 17. Oval bowl with rim partially covered by glass crystal, decorated internally with a spiral of white zanfirico.

In fact, we can see a shattered unity, a unity the artist had considered irresolvable. And since it was so profound, it is not yet configured in any clear terms of correspondence with reality. It is also just as clear that the lines of the breaks in each “broken” glass do not preclude the possibility of recomposition. It is a stock of pain, that we all acquire during our lives. Archimede Seguso has again succeeded in taking these emotions and sublimating them in the beauty of color, the luminosity of transparencies and mainly the purity of form that has always been his highest goal and in which in his soul rediscovers the serenity that for a moment he feared was lost.

Peasants, 1959, h. cm. 42 x I. cm. 17; cm. 40 x 18. Figures in solid white alabaster glass alabaster glass and shaded green.

Swan, 1957. Swans on a crystal green transparent base of milky glass in ruby and (cm. 14) and shaded blue (cm. 16) with gold dustings.

Horses, 1994, mis. cm. 34 x 48. Four heads of galloping horses, a solid work on a sinuous glass crystal with gold.