NOTEBOOK 6

The President of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi, and Archimede Seguso in 1952. They are in Venice at the

Biennale, in the pavilion which held the exibition related to glass art. The maestro from Murano exhibited his very fine filigree, lace trimmings, weaving and webbing with great taste combining a surprising modern style through to the vastness of Venetian tradition.

PRESENTATION

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF GLASS. THE BIENNIAL

This edition of the “Quaderni di Archimede” is dedicated to the Biennale in its one hundredth year. This is an important date for Italian artistic culture; and important are the conclusions that one can draw, even from art exhibitions which have not been made part of history as much as we may have desired. From our point of view, which is relative to a beauty which goes beyond the instruments and the canonical forms of art, a comparison would seem very useful between those which were once called noble arts and the so-called applied arts. The historic glassworks section of Ca’ Pesaro, even in its synthetic form, which one may very well argue about, has at least the merit of allowing one to use, in making comparisons, evaluation parameters which for once escape from convenient but artistically inadequate schemes. It is here that, in our opinion, Archimede Seguso’s glassworks stand out.

Archimede Seguso mentre visita la mostra: “Venezia e la Biennale. Percorsi del Gusto”, allestita a Ca’ Pesaro in occasione dei 100 anni deI Biennale.

The first essay of this Quaderno gives us the main points of an argument which is worth discussing: that pertaining to the often ambiguous relationship between the art of painting, which dominates the century, and the “decorative” art of object-making, such as glassworks. The second essay takes a closer look at the Biennale and particularly at the stages of Archimede Seguso’s participation; Seguso is considered the only “complete artist” in glass-making, that is designer and, at the same time, producer of his own works. In particular, one must pay great attention to the lace trimmings, the filigree and all the sign structure which propels the modern style of the maestro from Murano through the vastness of Venetian tradition. The third essay dwells upon the other aspect of Archimede’s: that of the mutating vibrancy of the colours in the “submerged” glassworks.

We believe that even in this Quaderno we have managed to offer a broad outlook, on a historic base, of what the art of glass-making is, showing that it is not just the expression of a sensible hedonism but, rather, an artform which draws from higher values, reflected in a society constantly on the move like the one we live in.

THE CENTENNIAL OF THE BIENNIAL

THE DECORATIVE ARTS:

MANY MISCONCEPTIONS

In 1895 it was decided to focus only on “high art”: ostracism of floral taste. The first settlements and the Revolution “regionalist” 1903. The national pavilions and the return of the applied arts. 1932: a space for itself, but also a ghetto.

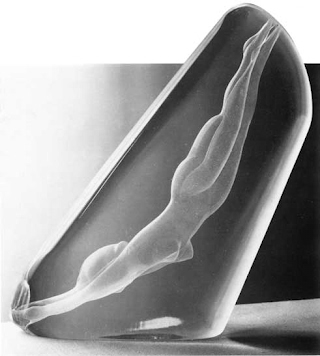

Biennale 1950. Nude, sculpture of a nude figure of iridescente glass, submerged in crystal.

When the Biennale was started, in 1895, it was meant to be solely an exhibition of “noble arts”, that is, based on painting and sculpting. This was, in some ways, the reason for the success of the Venetian event. Previously, in 1887, a National Artistic Exhibition had been set up in the same place, the Giardini or Gardens. Such exhibition was open – as was common then – to the so-called applied arts, but it did not succeed. The brainchild of the Selvatico-Fradeletto-Bordiga trio was aiming to get the most of pure art, getting more and more so in line with the symbolist-decadentist school of thought: it would therefore concentrate more on the secessions of Munich and Vienna than on French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Hence the literary inclination which characterized the first editions of the Biennale, a prime example of which is the “Supremo convegno” (Supreme Meeting) by Giacomo Grosso, which constituted the first scandal (and therefore the rise to popularity) of the Biennale.

We can see then, from the very first Exhibition, the formation of a preliminary issue. The “Supremo convegno” (a painting that, nowadays, would be depicted as grotesque) showed five naked women voluptuously leaning over the coffin of a bloodless Don Juan with a large moustache. It wasn’t by chance, thanks to the impression it made which was deemed to be obscene (there had also been a ban by cardinal Sarto, who became Pope Pio X), that the painting had a morbid power of attraction. So much so that, even though exhibited in a room not included in the normal area, it won the highest recognition from a popular jury. Even a large portion of the 516 exhibited paintings and sculptures followed this trend: sophisticated intellectualism, subtle eroticism, shivers of existentialist decadence, showings of affected conventionalism. At the same time, anything that could be connected to the “industrial arts” was looked upon with disdain; such arts were deemed to be inferior, even though they were fruit of the exquisite Viennese style of the Secession period. The Liberty style, particularly in its expressions of decorative elegance, was banished. Oddly, it was just then that the aesthetic glamour of Liberty was reaching its peak (it suffices to mention Horta, Guimard, Mackintosh, van de Velde, Hoffmann).

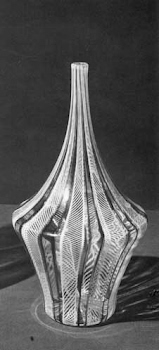

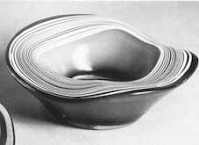

Biennale 1952. Vase merletto. Vase, drop shape, flattened, triangular section in transparent glass decorated internally with white lace.

Vase “ribbon pattern”, 1952, h. cm. 28. Vase with oval section decorated internally with white and amethyst glass in a diagonal pattern.

All of this stands as proof of the Biennale’s traditionalist concept in separating between liberal and decorative arts. As early as in the third edition, in 1899, this prejudicial stance started to fade away. A few bas-reliefs were exhibited (Vincenzo Cadorin, Del Bo, Charlier and others), particularly, in the “sala scozzese”(scottish room), the works of the four “ragazzi di Glasgow”(boys from Glasgow) , with Mackintosh in front: pillows, books, glassware, even posters. The historic turnaround, though, took place in 1903: the exhibition remained involved in painting and sculpting as far as the international scene was concerned, yet it opened up to an unprecedented concept of “regionality” for the Italian part. Fradeletto, then regional secretary, made clear his opposition to the “childish and wild expressions of the so-called floral Style, inappropriately referred to as Liberty Style”, with everything “artificial and vain, inconsistent and transient” which was connected with such style. As if to say: the Biennale was interested in the universality of art, and not the whims of fashion. The regional Italian rooms were connected to the “variety of regional instincts of the Italian genius”. It was then that, under this new outlook, various applied art objects and furniture, including glassware and ceramics, were introduced. It was a time to welcome a new “atmosphere of return to Italianness”; it must be noted that this was still twenty years before the advent of the first fascist rhetoric.

Vasi Spiraline, Spirals, 1954. Rennaisance half-filigree interrupted by braidings of threads which break the uniqueness of the weave. From left to right: Vase, sphere shaped, with cone shaped bottleneck bordered by amethyst threads, decorated in a white half-filigree interruputed by loose braidings of amethyst threads. H. cm. 17. Vase, sphere shaped with clover shaped bottleneck, in transparent glass, decorated in a white half-filigree interrupted by loose braidings of amethyst threads. Vase, irregulare shape, in transparent glass with cylindrical bottleneck bordered by amethyst threads, decorated in a white half-filigree interrupted by loose braidings of ametyst threads. H. cm. 21.

Biennale 1968. Vases, threads, “ognon”. Vases with several bottlenecks which are regular or decreasing in size, with decor and colour grading given by the superimposition of lilac or opaque white vertical lines.

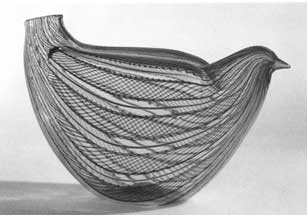

Above and to the left, Piccione a festoni,(Festooned Dove) 1954, h. cm. 15. Small vase in the shape of a bird with an opening on the tail in transparent glass decorated internally with diagonal segments of amethyst and white alternating continuous threads.

The first foreign rooms were set up two years later, in 1905; and in the following edition (1907), an innovative concept was introduced, embodied by the Belgian pavilion, which today is seen as absolutely brilliant: the Municipality started selling off plots of land at the Giardini, upon which to build national pavilions. As early as 1909, the pavilions of Germany, Great Britain and Hungary were set up, subsequent to the Belgian one. This new structure of the Exhibition allowed the Municipality to save large amounts of money (even for the one hundred year edition of the Exhibition, foreigners covered expenses for several billions) while giving more freedom of action to the various nations. It is in this way that, in 1909, year in which Archimede Seguso was born, decorative arts made their way back to the Biennale in different ways and forms. Basically, decorative arts were thrown out the door and let back in through the window. The one hundred year edition of the Exhibition, which is presently set up at Ca’ Pesaro thanks to the Municipality of Venice, highlights the astounding beauty of objects which have been exhibited in the Biennali up until the beginning of World War II. Quite prominent are Galileo Chini’s decorated vases, Giovanni Beltrami’s glass window, Ernesto Basile’s furniture, the wooden flower case by Vincenzo Cadorin, Giuseppe Norsa’s door covers, Giacomo Vivante’s earthenware, and the glass and wrought iron works by Umberto Bellotto, just to mention Italian artists of the period before 1914. Yet, there has always been a sort of ostracism towards all that wasn’t either painting or sculpting: so much so that in 1928, with Maraini as secretary, Chini’s marvellous decorative cycle on the dome of the central pavilion was covered with the works of Gio Ponti.

Bottle-Vase, in transparent glass decorated vertically with diagonal segments of white and amethyst alternating and parallel continuous threads. H. cm. 34.

A new concept of ornamentation, whose main representative in Venice was Ponti himself, was taking over. In 1934, Carlo Scarpa made his debut as glassworks designer; and surely, that was the year during which the Bauhaus style and abstract art in general (from Gropius to Mondrian) became popular. It was then that, due to a maximalist interpretation of art, also upheld by fascism, all which was considered craftsmanship was confined to a specific area: the Venice pavilion, set up in 1932 for the decorative arts, glass works in particular. It was a recognition but also, as one would say today, a transformation into a ghetto. As a matter of fact, the distinction between independent artistic creation and artisan-industrial production was never fully discussed; such distinction is still cause for a lot of misunderstanding, particularly with regards to glass. Still, the Venice pavilion performed a useful function since, by creating a competition between the best glass works shops in Murano, it contributed to modernizing their style by opening it up to the great influences of European art. It is from that point that Archimede Seguso becomes one of the most praised protagonists.

Following the turmoil of 1968 even this distinction came to an end. And, in 1972, the Venice pavilion was closed.

THE CENTENNIAL OF THE BIENNIAL

WHEN THE CRAFTSMAN TURNS ARTIST

A key point: the distinction between designer and executor. A “complete” master in the historical overview of Murano glass: Archimede Seguso. Lace and filigree in close relationship with the painting of signs of the time. Technical quality and an unmatched unique creative flair.

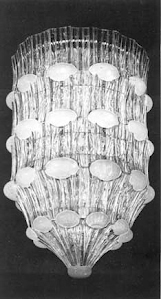

Biennale 1958: Lamp, bubbles

The one hundred year edition of the Biennale, in its section of Ca’ Pesaro, dedicated to glass artworks, allows one to follow the artistic journey of Archimede Seguso throughout his periodic participation in the Venice pavilion. It is here, in this setting of the Biennale, and particularly in a direct comparison with the “greater” works of the maestri of painting and sculpting, that one can measure that quid of artistic genius, and therefore of individual aesthetic quality, which sets apart those who have been relegated to the role of craftsmen by some ancient custom. What does working on a material as difficult and unreliable as glass actually mean? Which role must be assigned to the designer, that is, he who draws up the art work, and which to the “producer” who physically creates such work? Where and how can these two fundamental functions be blended into one?

Too many misunderstandings, and quite a bit of hypocrisy, have weighed upon, and still do, on the entire sector of artistic glass-making, particularly within the realm of the “family” from Murano, which certainly is the most developed technically, and not only in Italy. As a matter of fact, an attempt has been made, in the catalogue “Vetro di Murano alle Biennali 1895-1972” (Murano Glassworks at the Biennali) (Leonardo publisher), at discerning between designer and producer. Many display cards actually contain just one name, which is generally the name of the designer, while the production is usually entrusted to a specialized company. And so it is that we can take a look at the greatest glassmaking artists of this century operating in Murano: Zecchin, Wolf Ferrai, Bellotto, Martinuzzi, Balsamo Stella and, further down, Carlo Scarpa, Flavio Poli, Ercole Barovier and others, up until 1972, year in which, as we mentioned previously, the Venice pavilion was closed and the custom of displaying artistic glass works at the Biennnali came to an end. One may wonder, are these well known nobodies truly the authors of the glassworks which are displayed each time? By observing closely, it may be seen that, within the vast expanse of the chronological realm, Archimede Seguso is indicated as covering both roles. He is, unequivocally, the most complete glass artist in Murano, having embodied the skills of the designer and those of the producer, that is of the master glassmaker. This may annoy some people – and we say it without any personal interest, with a spirit of objectivity – yet, it is an unobjectionable fact, which shouldn’t, however, lessen the work of many other artists who have made Murano glass art famous in this century, introducing it in the most vibrant currents of European taste.

Whoever has looked with inexperienced eyes, at least once, at a glass production furnace, can comprehend at once how complex glass-making can be and how important (better yet, decisive) are the hand skills involved in the various technical procedures used in blowing glass as well as shaping solids of the material. Much more so than in ceramics, the fluidity of glass demands a manual, therefore personal, control which can be described only in a very approximate manner during the phase of drawing up the design on paper. This fundamental argument has always been avoided, even by the most attentive historians and reporters of the art of glass-making. As a consequence, some extraordinary master glass artists have gone unnoticed, if not ignored altogether. This may explain the stylistic differences, intended as personal signature, which can be noticed in glassworks of the same designer even in the same year, without taking into consideration certain discarded pieces. As an artistic activity, it is difficult to account for such peculiarity, which may instead be found in the broader activity of craftsmanship which has to conform to commercial interests.

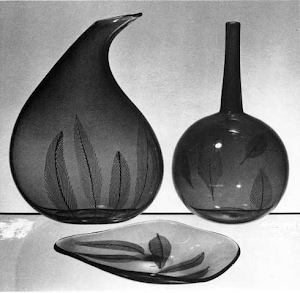

Biennale 1956. Vases and bowl, feathers. Vibrating reed feathers of coloured glass immobilized in the glass of the vases and bowl. Vases and bowl “feathered” in yellow shaded ruby glass decorated internally with feathers of different opache colours. H. cm40; h cm38; diam. cm 31.

n this respect, he has always been given credit for such qualities. Let’s return to the itinerary offered by the one hundred year celebration of the Biennale at Ca’ Pesaro. The year in which Archimede Seguso’s stylistic personality appears at its fullest is 1952, when he exhibited a group of vases trimmed with lace, that is, created with the finest tangle of white thread or amethyst, a result of (as indicated in the catalogue) skillful elaboration of reeds. More vases, fruit of the same technique, were exhibited two years later: the finest filigree as free entities in space, thick yet fanciful webs, reeds twisted into curvilinear shapes. Looking back at these fascinating objects, they stimulated remarkable stylistic reference points, with the ethereal clearness of their flitting and, at the same time, compact shapes. Informal signs with oriental roots, (which had Wols, Tobej and Michaux as leaders) had yet to appear, during those years at the Biennale. Still, Archimede Seguso had recognized the signs of the times to come, and blended his Venetian style (therefore oriental) with the modern taste, which was in full expansion.

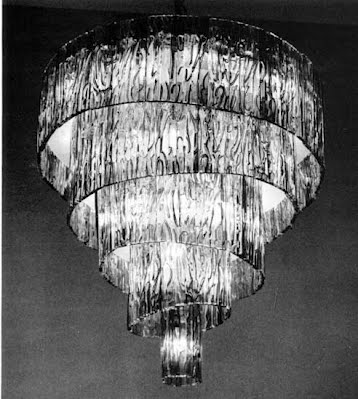

Biennale 1958. Chandelier , of bamboo-like pieces of multicoloured glass and crystal lace decorations.

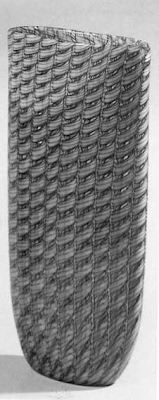

Black and White Pattern, decoration in a black and opaque white pattern., h. cm. 46.

It is quite common to consider these glassworks as part of a historic movement which was then taking shape in painting. That very same Informality flowed, some years later and with a more rigorous sign structure, into the Op Art movement (from Vasarely to Riley). Even in this case Archimede Seguso delights you with wonderful pieces: it is a sign of the times but also (and this must be emphasized) an awareness of the Venetian cultural-environmental roots. How can one not correlate with the “great mother of the lagoon” those marks which weave through space with incredibly entrained rhythm which is at the same time as free as can be conceived? The glass becomes vibrant air, thin melting colour, perhaps the quivering motion of waves or tall grass, reflection of vibrations which make one of earth, water and sky. In other words: one can detect the existence of an international artistic taste (I repeat: international) together with a response to the suggestions of the categorial Venetianness. All of this reflects not just one instance of the artistic inventiveness of Archimede Seguso, but a whole path that, even in the itinerary of the Biennale, meanders perfectly in consideration of the initial assumptions.

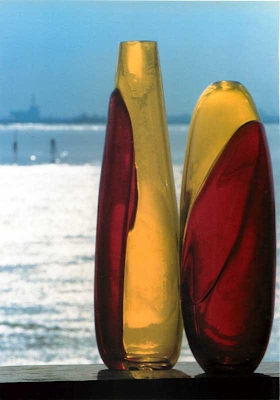

Biennale 1966. Vases superimposed colours. Vases with vertical shadings from ruby to yellow with a blue ribbon glass appliques. Brief collaboration with Prof. Rincicotti with whom Archimede Seguso processes a series of acid decorations on plates and vases, creating chromatic effects on the thickness of overlapping pieces of glass. Another result of this great collaboration is the great sculpture presented in the Biennale of 1966, in which elements of slates of coloured glass, used as pieces of a mosaic, are framed in a structure of iron-cement.

Biennale 1962. Continuous threads, opaque white threads placed vertically and parallel, following the curves of the object approaching or distancing themselves without ever losing direction or number. Bowl, continuous threads in transparent glass with semispheric stand. H cm 15.

The weaving filigree, the lace, the winding milky coated threads, the feathers, the grooved bands, the continuous threads, the starry filigree: all the variations which Archimede’s imagination has brought to life in countless astounding glassworks, are not a result of chance or servile obedience to trends, nor of commercial interests or games. This artistic vein, which deserves to have a place of its own next to more famous examples of contemporary pictorial arts, does obviously not rule out the coming to life of Archimede’s inventive talent. For example, in many works it is colour which, with the finest variations of the submerged, comes out triumphantly; in others, the sculpting qualities prevail (we have already noted several times the affinity with masters like Arturo Martini, Marino Marini and Messina). Until, perhaps, one steps into that phenomenal large polychromatic sculpture, made in 1966 in collaboration with the painter Luigi Rincicotti, in which elements of coloured slates of glass, almost used as pieces of a mosaic, are woven in a structure of reinforced concrete.

The game, polychrome sculpture, h. cm. 207.

Vase, starry filigree, in transparent glass decorated internally with a white wowen filigree and starry pattern, h. cm. 35.

Then, as we have already mentioned, the adventure of the Venice pavilion ends, as a result of a dispute which today can only be seen as negative and unproductive. And this also spells the end of a series of glassworks exhibitions at the Biennale; but not the end of Archimede Seguso’s creative journey, eighty-six years of age today and still very active, day after day, in his multiform forge shop in Murano. In the meantime, many misunderstandings are being cleared up; and the history of glass-making in Murano takes up a more accurate historical dimension. We start to see beyond the trends and pick out those contributions which are truly artistic creations; and when these contributions are supported, as is the case of Archimede Seguso, by a unique expert technical opinion, the artist’s reputation steps out of the realm of artisans and pure designers as well.

Biennale 1964. Vase, soft shaded undertones, where the grinding produces an effect of colours in motion

ARCHIMEDE SEGUSO’S PARTICIPATON AT THE BIENNIALS

1936 XX Biennale

Boccia Bullicante, h. cm. 16, diam. cm. 22, designed by Flavio Poli. Bubbles of equal size arranged in layers stacked in the mass of thick glass.

1938 XXI Biennale

Hippo, h. cm. 8.5 design Flavio Poli. North frosted green glass sculpture, crafted in solid glass depicting a hippo emerging from a single block with this form.

1950 XXV Biennale

Nude sculpture, nude of black iridescent glass in the crystal.

1952 XXVI Biennale

Vases and bowls “Lace” Dense network uninterrupted three-dimensional texture or “eyes” or “windows” in white opaque or amethyst glass.

Vases and bowls “Fantasia tape” Interior decoration in white and amethyst glass patterned diagonally.

1954 XXVII Biennale

Vases and bowls “Composition milky” striped bands in rows of milky white, distinct and close, but not criss-cross, curved with different accents.

Bowl, white threads

Vases and bowls “spirals” Half Renaissance filigree interrupted by a weaving of white or amethyst twists which break the uniqueness of the texture.

Vases and bowls “festoons” striped bands of filigree segments with milky white and amethyst, placed vertically or in bands on the object.

1956 XXVIII Biennale

Vases and bowls “Feathers” Feathers vibrant colored glass reeds immobilized in glass vases and bowls.

1958 XXIX Biennale

Vases and bowls “Fantasia white-black” patterned decoration in black and white opaque glass

Ashtray in Alabaster glass uneven winding edge formed by the overlapping of several layers of alabaster glass. Ashtray, alabaster glass. Lamp with concentric multicolor bands, oval shaped bubble lamp

1960 XXX Biennale

Vase and bowl, blue

1962 XXXI Biennale

Vases and bowls “continuous filaments” opaque white wires placed vertically, always parallel, following the curves of the object, approaching or distancing themselves without ever losing direction or number.

1964 XXXII Biennale

Vase and Bowl “Aleante”

1966 XXXIII Biennale

Vases Vases overlapping colors with vertical hues from ruby to yellow with blue ribbon appliques.

Vases overlapping colors in yellow glass with transparent overlays or asymmetric flows of red glass.

Polychrome sculpture “The game” Short collaboration with prof. Rincicotti with which Archimede Seguso processes a series of acid decorations on plates and vases, creating chromatic effects on the thickness of overlapping pieces of glass. Another result of this collaboration is the great sculpture presented in the 1966 Biennial, in which elements of slates of colored glass, used as pieces of a mosaic, are framed in a structure of iron-cement.

1968 XXXIV Biennale

Vases and bowls “Watermark Starry Decoration of tiles with white filigree pattern of stars.

Vases and bowls Vases, threads, with several bottlenecks which are regular or decreasing in size, decor and colour grading given by the superimposition of lilac or opaque white vertical lines.

1972 XXXVI Biennale

Vases “Optical Art”

Vases herringbone pattern, milky coated filament internal decoration in a herringbone pattern

Vases Petal: interior decoration, at the base of the object, the decoration is in a petal pattern.

Vase and bowl with soft shaded undertones where the grinding produces an effect of colours in motion.

THE CENTENNIAL OF THE BIENNIAL

THOSE “SUBMERGED” DIONYSIANS

The drive of the fluid and changing color is apparent in the vessels created by Archimede today as yesterday. A design from the North, an elegant color that comes from the great Venetian taste. As the melting of the Algor of the solid and essential forms of the ’50s

Biennale 1958: Lamp Vase in blue ruby shaded glass with transparent glass base, 1958. Piece on display, among the others, in 1990 also in Otaru, in Japan, in the exhibit dedicated to the maestro Archimede Seguso.

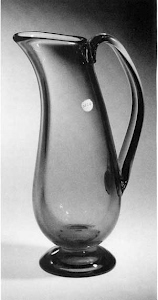

Even in glass art, as in painting, two different aesthetic categories compete with one another: the Apollonian and the Dionisyac. In the former the elegance of a “classic” modulation, that is, balanced and structurally congruent of form-colour prevails; the latter emphasizes the expressive aspects, often pushing signs and chromatic aspects to an extreme. The historic sequence of this one hundred year celebration of the Biennale confirms that both aspects are embodied in Archimede Seguso’s production, albeit in a time span of fifty and some odd years. Apollonian are certainly the vases we have already talked about, with their fine weaving and webbing of signs on a texture of extraordinary lightness and transparency. Dionisyac, instead, are those other works in which the main element of the Dionisyac category is predominant: the symbolic-expressive force of colour. It should be pointed out that quite often both aspects go together well: so that Archimede’s classical style can be considered as extremely well balanced, supported as well by a proven artistic personality. The “sommersi” by Archimede, created in these last few years, but on the scene since the forties and earlier, represent indeed the triumph of colour, as primary vital pulsation. It is a well known fact that it was during the first years of the fifties, that simple and well blocked forms, massive and elegant at the same time, would impose themselves. It was just then that Archimede Seguso made a journey to Denmark and Scandinavia, to Finland and Sweden. Here, he was struck by the extremely pure forms of the local craftsmanship which, in effect, had already become popular in the South, even among the designers from Murano. Yet, those forms seemed a little too “frigid” to Archimede, lacking that warmth which could not come from the Southern sun, that is, from a Mediterranean sensitivity. And so, once the maestro made his way back to Murano, he tried to give, to those forms of great thickness and essential geometry, a chromatic sophistication which did not exist in the North. The “sommersi”, with their evocative and enchanting variation of colours, were born and were developed throughout the years concertedly with works in lace and filigree, in other words, in tune with a renewed tradition of the light Venetian style. It was as if colours would melt, become air, almost expanding in the fluid glass in motion. Everything would become magmatic, and transform itself in the primary symbolic force of colour. The vases from those times and the ones from today are a clear example of how the exquisitely Venetian sensitivity of Archimede Seguso can “warm up” a design which, in the North and generally outside of Murano, would appear of a glacial and rigid purity.

Picher with base, green and amber glass, 1954. Piece on display also in Otaru, Japan, in 1990 in the exhibit dedicated to the maestro.

Presently, Archimede’s submerged vases are displayed at a parallel exhibition on the subject which Antichità Micheluzzi have set up in their elegant location next to the bridge of the Maravegie (Venetian “wonders”) in the central area of the Accademia. Other works by Archimede Seguso are on public display, other than at Ca’ Pesaro in connection with the sequence of historic glassworks of the Biennale and at Passage De Retz in Paris for the exhibition “L’art Du Verre a Murano au XX’ime siecle”, at Palazzo Bellini in Comacchio for the “Maestri vetrai creatori di Murano del ‘900” exhibitions, and at the great and prestigious Museum of Glass in Corning, U.S.A., for the exhibition of the “murrine”.

Indeed, Archimede Seguso’s creations, both historic and current, are continuously being dispatched all around the world. They are a testimony to an authentic “renewal within tradition” which the artistic glassworks of Murano have undergone, beyond mannerisms and whims. And it is within this context that the artistic personality of Archimede designer and producer, in other words a “complete artist”, asserts itself among those who still love and appreciate the pieces of a Beauty which defies the relentless passage of time.

Below: Vases superimposed colours, 1966. Vases in transparente bright yellow glass with red superimposed on the lower part. H. cm. 26 e cm. 35.