NOTEBOOK 7

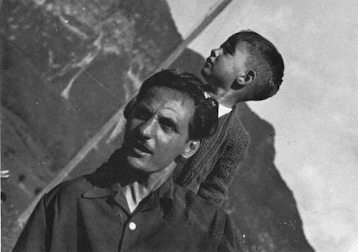

Summer 1942, Archimede Seguso, convalescent, in San Martino di Castrozza. Behind him, his young son Gino.

PRESENTATION

TO OVERCOME THE COMMON PLACE

The “Quaderni di Archimede”, now at their seventh edition, aim to look at current trends – in this case, in the world of glass- within the context of a “culture in flux”. And in the occasion of the centennial of the Biennale, which was dealt with at length in the previous issue, there are new grounds for interest. An exhibition in the prestigious Casa dei Carraresi at Treviso gives a brief outline of the master of Murano’s participation at the Exhibitions held from 1936 to 1972 and reaffirms the affinity between the art of glass-making and the art of sculpture in his theme of animals (one of Archimede’s classics) executed in 1995.

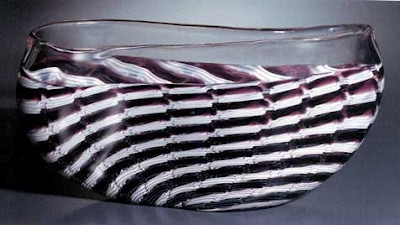

1934. Bowl, spirals with two side openings formed by the partial union of the border, decorated with milky filaments braided freely into spirals, h. 11 cm, I. 26 cm. Plate, transparent glass decorated internally with amethyst and opaque yellow ribbon filaments, h cm2, 5, diam. 22 cm.

Very rarely has recent criticism made direct reference to the stylistic affinity that can exist between glass production and sculptural plastics. Archimede Seguso however provides a luminous example since he started out in his early years, soon after 1930, earning the name of “Master of Animals”, by creating solid sculptured figures. More over, the reappearance in present-day culture of “naive” motives, with infantile or primitive overtones, is in perfect harmony with this line pursued by Archimede for over sixty years. A comparison between Jeff Koons and our master of Murano is not after all so out of place. It is simply a question of breaking away from a perspective that is still too conventional by glass critics.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

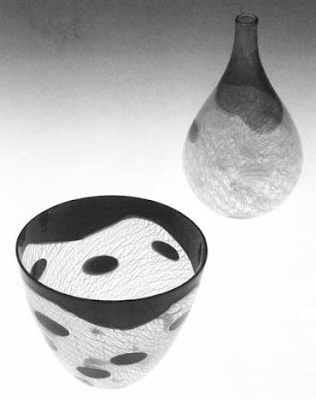

1958. Bowls, black and white pattern. From top to bottom: circular bowl decorated with black and white opaque glass, h. 15 cm, diam. cm26; round bowl, h. 10 cm, diam. 17.5 cm; triangular bowl with rounded corners, h. 10 cm, I. 16.5 cm.

THE CENTENNIAL OF THE BIENNIAL

Archimede Seguso in 1938 presents himself as a sculptor and this is almost a mission statement. Cultural parallels in the retrospective of Treviso. Subtleties of signs and explosions of color. From the informal to the Op Art: a path in search of a total Venetian taste.

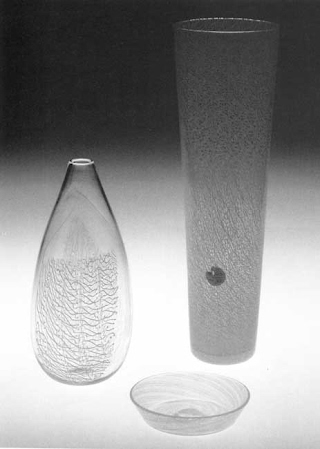

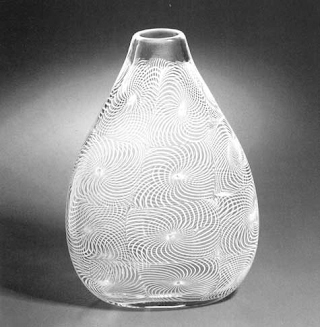

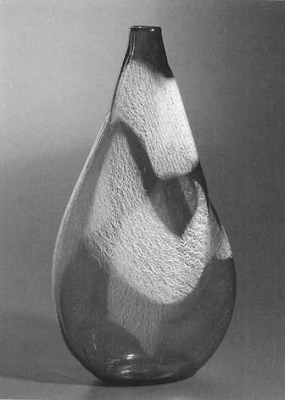

1952. Lace Vase, oval clear glass vase, decorated internally with two symmetrical spots of white lace and amethyst, surrounded by threads in the opposite color of the lace, h. 26 cm, I. 11.5 cm.

Lace Vase, conical shaped log in a light amber glass with gold shading, decorated internally and evenly with white lace, h. 39 cm, diam. 12 cm. Bowl, flat bottom of transparent glass, decorated internally with thin white spiraling threads, h. 2.5 cm, diam. 13 cm.

Our times appear all set to become history. It is said that the task of present-day culture is to “create creation”, which, in a certain way, favours criticism. The centennial of the Biennale, as devised by Jean Clair, is based entirely on “recreating” the past. This concept is even more evident in the field, defined until yesterday, as the decorative arts. Every period has a style of its own; a style that is later recovered, interpreted and (irremediably) distorted by posterity and it is this distortion that becomes “recreation”. For this reason, cultural incentives are never lacking, even when it seems – and probably quite rightly – that precious little now remains to be created; with the consequence of the prevailing of “rehashing”.

To review with a critical eye the history of Venetian glass throughout this century, as the Biennale has done, is in itself a discovery – at times even a marvellous discovery, as we observed in the previous issue of these “Quaderni di Archimede”. Now the exhibition at the Casa dei Carraresi at Treviso, dedicated to the famous maestro of Murano’s participations at the Biennale exhibitions, starting from as far back as 1936, provides an excellent opportunity for a new (albeit critical) “recreation”. At Ca’ Pesaro, where the organizers, in the “Venice” pavilion, have made an understandable endeavour to trace some of the principal lines that have marked the evolution of glass during the 1932 – 1972 period, Archimede’s appearance on the scene dates back to 1952, with stupendous lace made of glass and striking patterned weavings in the illusory space of transparent glass. The Treviso exhibition has revived the historical beginnings which date from 1936. It is symptomatic that the Biennale of 1936 chose to highlight Archimede’s traditional high quality profile: a bottle swarming with a myriad of tiny bubbles which appeared to move inside the vitreous blue mass. It was only in the following edition, held in 1938, that his real sculptures, made of solid glass, were exhibited. The Hippopotamus, displayed that year, has since become one of the most famous examples of pre-war Murano artistic glass, with that sinuous mass emerging from the water in a solid block. A similar piece is on exhibit at Treviso: a Fox in the famous north green, again a solid block, and a vase and bowl in green-gold with tiny bubbles. And we can but only admire the quite unique mastery in his use of sculptural techniques on such a fragile material as glass. We discover in Archimede that same stylistic temperament found in the young emerging sculptors of the period: Messina, Manzu, and even Marino Marini, to name but a few.

1937. Vase and bowl of green and transparent glass, with gold, with layers and irregular form with external bumps: h. 24 cm; Cup: h. 8.5 cm, I. 25 cm.

1964. Vase and fish aleanti lightly shaded blue crystal glass vase, in which the grinding creates an effect of chromatic motion, h. 27.5 cm; I. 20 cm; fish in transparent and opal solid glass, with sinuous, beveled and thinned back, diag. 30 cm, diag. 29 cm

1953. Vase, lace, h. 19 cm clear glass vase with oval section with slightly falling edge, wrapped with lace interrupted by a deep amethyst crystal inlay.

The lesson imparted by the great Arturo Martini is there for all to see: the essentialness of the mass unwinding in its natural rhythm with a sort of allusive representation typical of the late ‘thirties. But all this should not come as too great a surprise for Archimede had since 1930 devoted much of his time to animal sculptures, so much so in fact that he earned the nickname “Master of Animals”. His sculptures encountered enormous success, but the cultural establishment (and consequently the organizers of the Biennale) privileged artistic glass which was more closely representative of typical Murano craftsmanship, historically through its refined execution, Archimede was already ahead of the times and showed a marked leaning towards sculptural art rather than glass-making art. He created his tiny animals from 3 until 6 o’clock in the morning, before beginning his “official” work. But then it is no secret that the history of art is full of such episodes. It has often been wondered why after 1938, the year of the Hippopotamus, the Biennale waited until 1950 before reincluding the young maestro’s works in the “Venice” pavilion. Apart from the war period (the doors of the Biennale were to open again only in 1948), Archimede had to contend with a troublesome affliction (migraines) which for many years obliged him to limit his work. In addition, after the war he threw himself life and soul into setting up and developing his factory, which was inaugurated on October 10th 1948, just as the first post-war Biennale Exhibition was closing. With the return to the Biennale in 1950, Archimede took part, exhibiting a “Woman Diver” in iridescent glass, submerged in crystal, a piece which has since been lost. At Treviso it has however been superbly substituted by a “Sleeping Woman” executed during the same period, a solid high-relief figure in iridescent crystal, from which the parallel drawn with Arturo Martini is clearly evident and confirmed by the beautiful original drawing displayed together with the sculpture. Again with these works Archimede gives a very fine example of high plastic sensitivity, revealing himself to be not only a highly- talented decorator, but a true sculptor.

1956. Vases Vase, feathers, inverted bell shaped clear glass, internally decorated with four blue feathers, h. 27 cm, diam. 25 cm, clear glass jar with oval section, slightly protruding mouth and base, decorated internally with five blue feathers, h. 22 cm.

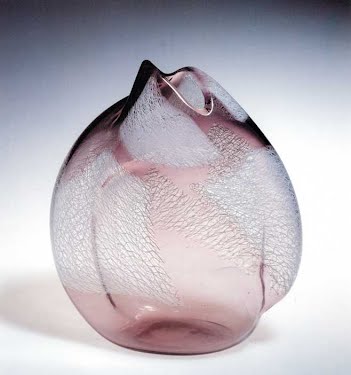

At the 1952 Biennale Exhibition another, complementary, side of Archimede’s art comes to light: the elegance of his motifs. With the opaque white glass bowl composition, with exquisitely designed spiral-shaped bands, glass lace, opaque white glass filaments and evanescent feathers, the subtlest of curves, impalpable filigrees and striking interweaves, it is clear that Archimede felt the appeal of the great informal style of painting of that time, while still not neglecting eighteenth century filigrees. Incredibly, he was close to the leading ‘”sign” artists of the time: from Tobey and Michaux down to Tancredi and even a sculptor like Zoltan Kemeny. No glass-art historian has ever referred to these parallels: but how is it possible not to liken to Tancredi’s painting some of Archimede’s vases with their thousands of filiform patterns dissolving into space? And how, a little later, around and after 1960, can one fail to discern the same cultural art that animates the Op Art of Bridget Riley and Nicholas Schoffer, both bubbling personalities of two Biennale exhibitions? Archimede naturally introduces his weaves of patterns and motifs into a Vivaldi-like “harmonious inspiration”. But then that is his Venetian nature. The Treviso exhibition, which follows in parallel participations at the various Biennale exhibitions, gives a brief outline of all this. The quality of the filiform bowls with their continuous patterns, striped bands and feathers immobilized inside glass is quite magnificent, as visitors to the other prestigious exhibition currently being held at Ca’ Pesaro, have been able to observe. Then, from 1964, sumptuous colours again began to appear at the Biennale. This is the third salient aspect of Archimede’s talent: perhaps not by chance they appeared at a time which foreshadowed and later characterized the general crisis of 1968 in many artists impregnated with exasperated (and mortified) nihilism: Archimede offers us the explosive joy of colour. A triumph of curiously sinuous vases with subtle tinges of changing hues side by side with clear-cut vases of superimposed colours. 1966 was also the year in which Archimede believed in form-colour architecture, and created, together with the painter Luigi Rincicotti, who was invited to collaborate at his factory, that great sculpture with “cloisonne” juxtaposed coloured glass, which seemed to have been born out of the golden era of Constructivism. Then the true Optical season arrived, to which the Biennale exhibitions of 1968 and 1972 bore splendid testimony. In the second Quaderno we have already mentioned a parallelism with the trend that was gradually materializing and how Archimede quite autonomously succeeded in interpreting it. From the very light overlapping reeds in the “onion glass” of 1968, to the herringbone and petalled vases of 1972, the “Archimede Line” invariably stands out, for here we are in a sort of Apollonian classicalness where the trend of the period is adopted in a vein of universal beauty.

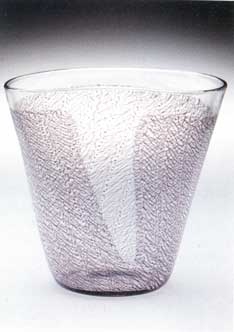

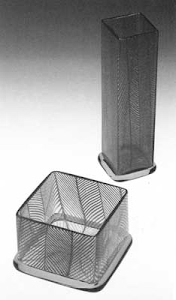

Vase and bowl, herringbone pattern, 1972. Smokey gray square glass vase, internally decorated with strings of milky filaments in a herringbone pattern, gray glass base, h. CM25, I. 8 cm; Bowl, quadrangular h. 9 cm; I. 14 cm.

Vase, milky coating glass composition, 1954. h. 38 cm; I. 15 cm. Vase, drop shaped with a long and flared clear glass neck, internally decorated with white criss crossing filaments design.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

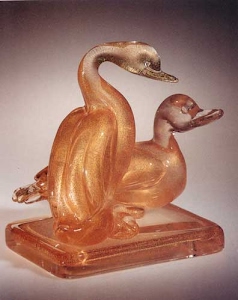

A pair of ducks in a solid crystal glass with gold on a square base with uneven surface. Mis.: h. 26 cm, 22 cm.

A group of three bears in solid glass crystal with gold on a square base with uneven surface. Mis.: h. 22 cm; I. 21.5 cm.

THE GOLDEN ARCAMEDE

The last series in submerged gold responds to a typical need of our time. Fom Jeff Koonsto Archimede Seguso: animals speak. A new name, “Arcamede”, for an experience born in the thirties. Sinuous lines and soft plastics.

1995. A group of three foxes, one crouching, solid glass crystal and gold on a circular base. Mis.: h. cm. 28; I. 25.5 cm.

The solid glass animals created by Archimede Seguso during the ‘thirties remain part of Venetian glass history: authentic sculptures which can be placed side by side with the creations of some of the most gifted artists (from Manzu to Messina) of that period. But the real miracle is that the “Master of Animals” has continued, albeit intermittently, to create his inimitable works of art all through his life-time -for well over half a century. Now, nearing the age of 86, Archimede offers us a new series of animals, as always in solid glass, but with a very fine gold grain embedded in the crystal. Several examples are on exhibit as part of the historical section of the Treviso showing.

These animals, which appear to irradiate a golden light, can be seen from two different view-points. Firstly, from a technical angle, the method of execution, where it is impossible to overlook the extreme firmness of the plastic form reinforced by the extraordinary cohesion in the sinuous flow of the mass. There is no discontinuance or hesitancy: everything unravels to produce a perfect animal likeness. One can admire them, handle and caress them: they have their very own structure that takes part in life, intended as a dynamically balanced organism. As though to say: Archimede has immersed himself in nature and modelled himself on her laws, without forcing nature’s hand.

Elephants in a solid crystal glass with gold on a circular base. From left to right: h. cm 32 h. 23.5 cm h. 25 cm.

This is of course all part of the artist’s skill; but there is something else that goes far beyond that skill: and it is the harmony which, again instinctively and intuitively, Archimede Seguso reveals in respect of the culture of the times. Art cannot be reduced to a mere formal exercise, however refined and sophisticated, as the vicissitudes of historical avantgardes would have us think. Art is also, and above all, gauged by its reference to the needs of its time. In the first of these “Quaderni” we reported at length on the “Rotture” (Breaks) those works which Archimede has recently realized in response to the endless physical and spiritual lacerations expressed – often with cruelty – by our times: these works are testimonies of embittered states of mind, to the extent that they have ended up taking up a clear symbolic connotation. Now, with the new series of animals, Archimede reverses the postulate with which he began. He feels the need, ever more pressing within society, for reconciliation and appeasement and consequently for a peaceful and cordial dialogue, far beyond any traumatic “rottura”. But let’s take a closer look at these tiny bears, elephants, foxes and squirrels, the funny little monkeys, the doves, ducks and placid little rabbits. They express calmness and serenity, a sense of friendship, especially when they are arranged in pairs or groups. But perhaps this is precisely what man needs today? Once again, pictorial and plastic art offers parallels which are seldom cited for with regard to glass objects. The success of a young American artist like Jeff Koons is indicative; he began to make a name for himself on the international scene at the end of the ‘eighties with his little Walt Disney style bears dressed as policemen and other plastic objects with both human and animal characteristics. Initially, they were defined as reminiscences of our childhood playtime, then very gradually it was discovered that they responded – as they still respond today —to a biological necessity of modern man. Regression to the world of childhood becomes a liberation, a rediscovery of one’s elementary needs and consequently, and above all, a return to maternal affection.

Pair of monkeys, one with a fruit in hand, solid glass crystal with gold on sinous contoured base. Mis.: h. 23 cm; I. 37 cm.

Foxes sculpted in a solid glass crystal with gold on sinuous contoured base. Sitting Fox : h. 23 cm; I. 30 cm; other fox: h. 20 cm;

And why should art not play a part in this need which emerges ever more insistently in today’s neurotic and mechanized world? Jeff Koons, at just over thirty, has realized it; and Archimede Seguso, with the wisdom of his eighty plus years, has done so too.

A pair of rabbits in solid glass crystal and gold on a circular base. Mis.: h. 37.1 cm, 25.5 cm.

Once again the result is gauged by the correspondence of means of expression with intentions. In these little animals, we repeat, everything reveals perfect cohesion. The sentimental aspect with a more or less conscious desire for affection, is rendered in the composed method of execution. Even representative intents can be excluded; in other words, by eliminating the recognizability of the animals. The plastic form, combined with the gentle play of golden colour, expresses itself symbolically. It invites a caress so that the man of today can unload his primitive and essential needs on to it. And glass, when modelled by the hand of an artist like Archimede Seguso, lends itself admirably to this manifestation of feeling.

The very attractive series has been given rather a strange name: “Arcamede”, signifying the fusion between Noah’s Ark and the name of Seguso. The master of glass has embarked on his ark those animals whose aim is to divulge the concept of calm and serene golden beauty.

Family of three ducks in solid glass crystal with gold on sinuous contoured base. Mis.: h. 30 cm; I. 38.5 cm.

A pair of squirrels sharing a walnut, solid glass crystal with gold sculpted on a square base with uneven surface. Mis.: h. 26 cm, 29 cm.

CULTURAL NEWS

ARTWORKS ON THE MOVE

The exhibitions of Archimede follow one another. From the Biennale of Venice to Treviso, from Comacchio to Forlì and Pesaro. The next “highlight” will be the Museum Dechelette of Roanne in France: from the fifties to the triumph of the dinner tables. The latest news in Liege and Luxembourg: the surprise of a double portrait, and finally in Paris with the “rotture” at Christmas. Art travels the world. It could not be otherwise, considering that we all live in the “global village”. And Archimede Seguso travels too, or rather, his works travel for him. In this period, exhibitions follow one another at close intervals, and each is presided by an organization that has to be perfect. Hundreds of glass objects must be dispatched to museums and galleries in Italy and abroad, many of the items are “historical”, while many others are collector’s pieces. When fame is achieved and prestige grows, everything comes as a consequence: honours and responsibilities alike. And now for a brief account of Archimede Seguso’s activities from the end of summer to the period of Autumn, the classic season for exhibitions.

1952. Bowl, amethyst and white pattern – h. 10 cm; I. 21 cm. Bowl, flattened shape with a sinuous section, internally decorated with bands of spiraling white and amethyst adorned themselves in turn by white and amethyst filaments.

At Treviso, in the splendid Casa dei Carraresi, cultural seat of Cassa Marca, the works of two distinct sections are on display: an overview of participations at Biennale exhibitions from 1936 to 1972 and a group of recent sculptures on the theme of animals (“Arca mede”). This splendid exhibition will only run for a short period: from September 18th to October 3rd. Naturally the items on show until October 15th at Ca’ Pesaro in Venice at the centennial of the Biennale will not be on display at Treviso.

1968. Vase, Filigree stars. Flattened oval vase with small glass neck, internally decorated with white starry filigree h. cm26, I. 18 cm.

Moving away from Marca Trevigiana and the Venice lagoon, we find the Comacchio lagoon. Here an exhibition of “Twentieth Century Master Creators of Murano” will be held, at which Archimede will exhibit 15 pieces realized from the ‘fifties to the present day, beginning with a splendid reed vase representing the first effect of modern filigree techniques. From Comacchio we go to Forlì. At the traditional bird show in Romagna a series of famous Easter eggs, which have now become true collector’s items, will be exhibited. Another move southwards brings us to Pesaro where the European Antique Trade Fair will be held from September 14th to 17th; Archimede will be honoured with a personal exhibition which will display a selection of his works from the ‘fifties as well as the famous great pyramid “My Europe” of 1992. A jump across the border takes us to the prestigious Joseph Dechelette Museum at Roanne, in the Loire district where a vast personal exhibition of Archimede has been announced for October to December: over a hundred pieces executed from the ‘fifties to the present day, starting with an opaline golden vase, dated 1950, through to a splendid arrangement of tableware a la fagon de Archimede. France has hosted the Venetian Master’s exhibitions on many previous occasions. In Paris, in December we shall again find “Rotture” (Breaks) a display which has already enjoyed great success last year and this year at Venice, Treviso, Florence and Lyon. From France on to Belgium (Liege) and Luxembourg. At the great International Show of Glass Artists, Archimede Seguso will present his latest creations, among which a “rottura” entitled “Francesca”, side by side with a sculpture which is almost its symbolical reverse, “Noi due”, a piece, in solid glass with embodied blown lace bubbles (a technique from the ‘fifties revisited in modern vein), representing two faces gazing affectionately at each other. Who are they? It is not difficult to guess: the octogenarian artist and his beloved wife.

Jar with lace, 1952, h. 35 cm; I. 19 cm. Vase, drop shaped, flattened form with irregular swelling small amethyst transparent glass cylindrical neck, decorated internally with large irregular weave in white lace.

Vase, lace with polka dots, 1954, h. 22 cm; I. 12.5 cm. Vase, drop shaped, with irregular amethyst band on elongated neck, decorated internally with thin white lace on which amethyst dots are scattered. Bowl, lace with polka dot, h. 13 cm, diam. 16 cm. Bowl with round section, irregular amethyst band on the rim, internally decorated with white lace on which amethyst dots are scattered.

1952. Vase, spherical shape with lace, oval section, with irregular and asymmetrical opening, of amethyst transparent glass, internally decorated with large irregular weave in white lace, h. 25 cm; I. 21 cm.

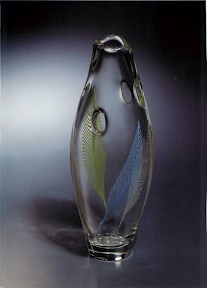

Below: 1956. Vase, holes and feathers. Elongated oval vase, irregular and asymmetrical opening, with four holes, internally decorated with green, blue and white feathers.