NOTEBOOK 9

The target-shooting team at the Murano firing range, 1929-1930. Standing, third from the right is Archimede Seguso, in the period in which he invented the “Bullicante”.

A few years later, Arcbimede Seguso won the Italian marksmanship championship.

In the photo we have identified the following people: from the right, standing Sante Viviani guard and gunsmith, Romano Tosi, Arcbimede Seguso, Norberto Moretti, Mr. Tis, Mario Santini marshal of Murano; Napoleone Barovier, Ferruccio Zanetti, Mr. Gasparotti, Mr. Perale, Umberto Cenedese, Silvio BarbiniII; seated, Stefano Cattelan, Annibale Zanetti.

PRESENTATION

WORDS OF TRUE GLASS

On the Island of Murano the language is “glass”. It is a noble language, so noble in fact, that long ago the Doge and the Council of Ten decreed that master glassblowers, “owners of furnaces” would have noble status and could therefore display their own coat of arms. And today? Nobility is declining. And even the pure language of Venetian glass has been contaminated: the sounds are crude, barbarian, even blasphemous. It just takes a poorly pronounced word, a slip of the tongue, and there you have it, the historical quality of great Venetian glass begins its decline. It’s happening constantly: just look around. Never before have bad taste and good taste, culture and anticulture clashed so strongly. Our era presents us with so many contradictions. We are the ones who have to make the choices on the basis of our sensitivity, our cultural background, our sense of responsibility, our conscience. Glass is even more fragile; it is fragile to the point that it can be slandered, massacred and humiliated. How many crimes are committed even at glassworks that descend from the noble houses of the “Serenissima”! Luckily, there are still those who treasure the pure ideal of beauty, beyond and above the crassness of mere trade. These Quaderni di Archimede pursue an ideal of “culture on the move” through which glass keeps on evolving while respecting tradition. The essay by Rosa Barovier Mentasti, well known scholar in the field of glass, that we have the pleasure of publishing, describes the quality of Archimede Seguso’s “bullicanti” from the technical and stylistic standpoints. The history of glass has and deserves a place in the history of art. The best production of the past can indeed continue, in new shapes, even today. This is the case of the Verde Serenella 18 collection that the eighty-six year old master has presented recently. The miracle of glass, of art continues and survives, in spite of everything.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

1937, Vase, barrel shaped in white glass (pulegoso) decorated with irregular and blown ruby spots. H. cm. 19

1948, Vase in bullicante crystal glass with gold, decorated with leaves applied to the exterior. H. cm. 32.

1948, Vase in green bullicante glass, decorated with leaves applied to the exterior. H. cm. 32.

THE BULLICANTI

Archimede Seguso intervened in the thickness of the glass with the “submersed” an even by using a technique of his own invention: the “Bullicante”.

1948, bell shaped lighting fixture in bullicante crystal glass and 3 crown lamp holders alternating with gold crystal leaves. H. cm. 80×35.

The prestige and quality of Venetian glass are partly the result of the fact that the master glassblowers of Murano have remained loyal to the technical and esthetic guidelines established for their craft during the Renaissance, and even earlier, in the Middle Ages. Over the centuries, this loyalty has meant refinement of manual techniques and therefore, rejection of procedures of mechanized series, high quality design and ceaseless adaptation of the offerings to the demands of an elite market. Loyalty to tradition, however, did not dampen the creativity of the Venetian glassblowers, nor did it enslave them to mere repetitions of old styles. The vitality of the tradition is even more evident in this century. It is a century characterized by uninterrupted and swift design innovations in that the finest of the master glassblowers, Archimede Seguso above all, have always succeeded in interpreting and sometimes even in anticipating style trends. This “updating” of the master glassblowers has not been limited only to design, it has also brought about changes in glassmodelling technique as well. Archimede Seguso first made a name for himself as a master glassblower in the ‘thirties. He was little more than twenty when he became the master glassblower at the Seguso glassworks. It was the beginning of a decade that was to revolutionize the world of Venetian glassmaking even more than it had been modernized by the Art Nouveau and Deco periods.

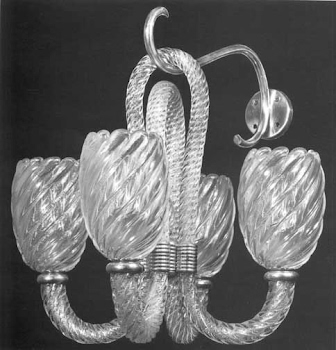

1950, Wall candleholder, gold crystal with rare submersed bubbles, curling ribbing pattern. H. cm. 32.

As in painting, sculpture and the decorative arts, the twentieth century style demanded an exaltation of plastic values that did not seem very compatible with the Venetian tradition of blown glass. During the first period of twentieth century glassmaking, that is from 1928 to 1934, designers and glassblowers turned to opaque and semi-opaque glass to overcome the effects of airy inconsistency, the merit and defect of Venetian glass. However, it was not possible to renounce transparency, the intrinsic quality of glass. So they turned to solid or thick glass that guaranteed a plastic effect without compromising transparency. The first trial creations of solid, animal figures date from the late ‘twenties and early ‘thirties.

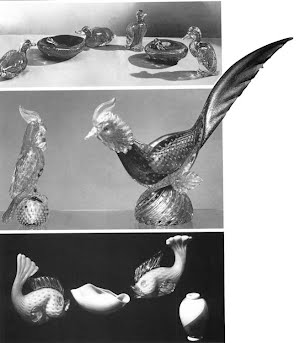

1938, Ducks and ashtrays in bullicante green glass with gold shading and in several layers. L. cm. 25.

1952, Parrot in gold crystal with amber shading on a green with gold shading sphere base; Pheasant in red glass with gold on a ribbed semi-spherical base in trasparent glass with gold. Cm. 21; cm. 32 x 50.

1952, Fish, in ivory with gold, decorated with evenly distributed bubbles, photographed with an ivory and gold bowl. Cm. 27.

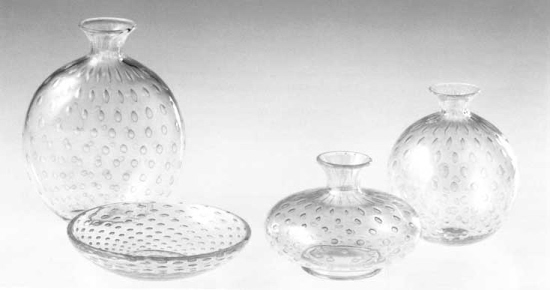

A real technical revolution took place at the Murano glassworks, and it was closely linked to the esthetic movement in which Archimede Seguso played a dominant role. Thanks to his plastic sensibility, and his skill in creating animal and human figures, with soft shapes, in natural-looking poses, he can truly be counted among the twentieth century sculptors. However, he had to develop a totally new way of working with glass since hot moulding of thick vases and solid animal figurines was the antithesis of Venetian tradition and of what he had learned during his apprenticeship in the ‘twenties. Quite soon, starting from about 1934, the Venetians discovered a new dimension in glassmaking, the inside dimension. Now the inside of the glass was enlivened and enriched by decorative plays, variations in color and light which were yet another innovation for Venetian glass. And it was here that Archimede Seguso came forward and did something striking with the thickness of the glass: the “sommerso” (submerged), layers of different colors, with “pulegose” (white glass) zones, with embedded goldleaf while the surface was enhanced by iridescence and acid etching; sometimes the techniques were combined in the same object. He also used a technique that he invented, the “bullicante” which, applied to decorative objects and glass for lighting fixtures, had the function of moving and creating luminous effects in consistent masses of glass, in severe twentieth century shapes. The “bullicante” effect consisted of overlapping layers of tiny, closely spaced air bubbles arranged in an irregular checkerboard pattern inside the glass. In addition to bringing depth to the decorative effect, the overlapping layers of bubbles created a sensation of motion, thus avoiding the monotony of too much even spacing. As in the case of other Venetian techniques, the observer, lacking familiarity with technology, was and still is dumbfounded by the apparent impossibility of arranging countless air bubbles with a rhythmic cadence in a mass of red hot glass. The same astonishment is aroused by the fine filigrees and “zanfirico”; the complexity of the Merletti (Lace) that Archimede Seguso created in the ‘fifties arouses even greater admiration. And yet, the master’s explanation not only sheds light on the logic of the process, it reveals the experimental approach used by the ideal master. Glass cannot be forced, it must be “assisted”, so that its distinctive features can be structured to the best advantage: reaction to heating and cooling, variable ductility in response to manual intervention and the thousands of tricks and secrets that comprise the technological heritage of master glassblowers.

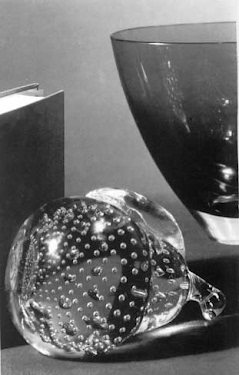

1953, Vases, in lightly ribbed crystal with gold,, decorated internally with a bullicante theme. H. cm. 37.

1958, Fruit in solid crystal and bullicante theme. Cm. 13 x 14; cm. 17 x 12.

By adapting a mould for lighting fixtures, Archimede Seguso created minute depressions on the outer surface of the molten glass attached to the pipe by using thin metal points. Then he placed the piece into the crucible so that it would be covered by another layer of transparent glass. During the process, a tiny air bubble would remain trapped in the depression left by the metal point. So it was the metal points that determined the even spacing of the air bubbles. He repeated the process several times, as many as six, and created the “bullicante” with six overlapping layers of bubbles. The effects could be accentuated by using colored glass for the innermost layers and by embedding goldleaf in a layer.

1955, Vases and amphoras in yellow, pink and light green opaline glass with gold, decorated internally with a bullicante theme.

H. cm. 18; h. cm. 32; h. cm. 22.

The Seguso glassworks presented the “bullicante” at the 1936 Biennale in Venice: a series of thick, “grey gold” vases pure ovals and torchons, the “Pomona” figurine and a submerged basket with an eel, octopus and a sea bream fish”. A spheric vase in elegant shades of violet-grey, with “bullicante” layers and goldleaf is part of the collection of the Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia; the bank, infact, purchased it at the 1936 Biennale. “Pomona” and the basket of fish are famous from period photographs. The bright green and crystal female figure with layers of “bullicante” decorations and goldleaf satisfies the criteria for twentieth century statuary. However, the piece that would bring joy to the most discriminating collector today is the green submerged glass basket, with its highly iridescent surface, filled with fluid fish, the fruit of Archimede Seguso’s great skill. Perhaps the basket is the archetype of the “bullicante” technique: the bubbles are spaced farther apart and are bigger. Unfortunately, no one knows where this piece can he found today.

1970, Sphere in crystal with inside three irregular bubbles. Diameter cm. 18.

After this official investiture, the “bullicante” technique was consistently used by the master in his bowls and vases, animal and human figures and lighting fixtures. The Seguso glass factory proposed avant-garde modern solutions: for lighting fixtures. Alongside of classic chandeliers it made ceiling fixtures and wall sconces, and thick glass screens embellished with “bullicante” or other decorations.

Certainly, the pieces that seem to harmonize most with the “bullicante” technique today are the green glass bowls with their softly wrinkled surfaces, and the fish, with flowing lines. Some of them are unusually sized, and only Archimede Seguso can make them with his keen eye for stylized shapes. In these, and all his pieces, there is harmony between material and shape, it comes from the “watery” suggestion created by the “bullicante” and this, in turn, justifies the unconditional esteem that these works enjoy and have enjoyed ever since they were first created.

1972, cup, glass jars and Bullicante crystal lavished with gold. H. cm. 21, diameter cm. 21 h. cm. 14 h. cm. 15.

CULTURAL NEWS

1996, Vases with base, light ribbing along the exterior in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 20; h. cm. 26; h. cm. 13,5.

FRESH GREEN MELODY

Among the smoke, the blazing heat and the light which, at times, becomes blinding, something is born. Can a furnace burning at 1350 degrees centigrade give forth music? At the age of 86, Archimede Seguso is somewhat hard of hearing. But who knows. They say that those who don’t hear well can “imagine” music, more or less like Beethoven. So here is the grandson, Antonio, age 28 who describes a melody to his grandfather during a workbreak. He draws a shape in the air with his hands; he’s actually thinking about a vase, but it looks as if he’s conducting an orchestra. Between the smoke, the heat and the light that is sometimes so bright that it is blinding, something is being created: a symphony, a piece of glass, music, a vase… The two men, grandfather and grandson, drenched in sweat, start to laugh. They can even understand each other through mere gestures. The furnace, Vulcan’s domain swallows and transforms. The red sea roars inside, while the flame, soft and gentle helps the master with his new creation, and the vase suddenly becomes music.

Vases and bowl, circular section with light ribbing along the exterior in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H cm. 33; h cm. 28; diametro cm. 21.

Vases with circular section and bowl with square rim, decorated with light ribbing in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 11; h. cm. 23; h. cm. 21.

Then, on Christmas day, the day of rest, grandfather and grandson turn on the record player. Yes, the melody they heard in that roaring furnace was the allegro vivace from Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony, not a famous piece (Schumann had defined this symphony as a “lithe Greek girl between two Nordic giants”), but it definitely has a brilliantly rhythmic motif in which clarinets and flutes play their parts with extreme elegance. “Yes, that was it!” they say practically in unison. Their faces glow. And once again they see that green, ribbed vase in that slightly sparkling color that comes through in thousands of iridescent glimmers. The vase is there and it creates a dual effect of classical rhythm and natural freshness.

1996, round pots with a slight rib percorsida Glass Serenity Green 18. H cm. 25 h cm. 22.

Perhaps this is the secret: going beyond Archimede’s extraordinary (and truly unique) technical experience, the Verde Serenella 18 vase—one of the creations in this highly admired series—is above all, a classic vase. Harmony, elegance, congruence of all its parts, geometric perfection: all the classic elements are here. And the totally unexpected comparison with Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony is perfectly appropriate. It marks the focus of that classicism that has been described as Viennese: the meeting between ancient and modern, between Greek sensitivity and a gentle Habsburg quiver. There is a sort of calm, abandonment to eternal, sublime thoughts: the perception of something that reconciles the intellect with the senses. During the Renaissance Luca Pacioli theorized about this marriage between art and mathematics in the wake of the great Pythagorean lines. Today it is difficult to reconvey that magic moment; our era is just too neurotic, dissociated, anxious and perennially on the move. Can we find anything in ourselves, in our restless thoughts, that can be considered even vaguely similar to Beethoven’s Fourth? Not an absolute masterpiece, but a cultural and emotional platform that will permit us to harmoniously stretch out our tired limbs?

1996. Vases and bowl with inward rim, decorated with a light ribbing in green Verde Serenella 18 glass.

H. cm. 25; h. cm. 30; h. cm. 9,5.

Vase, round, vase with base and bowl with outward rim, with a light ribbing along the exterior, in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 14; h. cm. 28; h. cm. 14,5.

The Verde Serenella 18 vase is still here, before Archimede’s and Antonio’s eyes. It emanates a sensation of freshness, of dew-covered forests, of crystal-clear streams. There is something attractive about that green, something mysterious. It carries grandfather and grandson back to old fables, to a world rediscovered with the wonderment of childhood. The gaze passes through the glass, it filters between the ribs and expands in the liquidity of the color until it is practically dazzled by the fleeting iridescence. Everything appears to be wrapped in a sort of perfection that is both natural and classic. The allegro vivace of the Fourth Symphony comes back on this wave of feeling. The music moves with the eye and merges with the vital transparency of a season of the spirit.

1996. Bowl, semispheric shape, round vase with cylindrical bottleneck, decorated with a light ribbing in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. Diameter cm. 28, h. cm. 32.

Vases with light ribbing along the exterior in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 16,5; h. cm. 20; h. cm. 12.

1996, Vase green Verde Serenella 18. H cm. 20.

Perhaps it was the enchantment of Christmas at home, away from the red, roaring flames, far from the furnace’s voracious mouth. Perhaps. But the miracle repeats itself. Someone arrives and the admiration captures all: at 86 Archimede, the grandfather has created another series of masterpieces. He directed his imagination towards the green forests, glimmering with liquid sparkle. He chose the formal structure of a classicism that leads from geometry to the sense of the absolute ideal; he impressed such a naturally cadenced musicality on those vases, so spontaneously vivacious … Yes, they are only vases. And yet, they seem to embody the beauty of a sonnet by Petrarch: “Clear, fresh sweet waters…” Even today it’s possible to create objects that veer towards a perfection that derives from a true understanding of the laws of nature. There is nothing extraordinary, nothing exceptional: a Grand Old Man who, in his wisdom as an eternal youth, has come one step closer to the mystery of life. Grandfather and grandson clasp hands: “Bravo, Grandfather”, exclaims the youth. He, the grandfather, cannot hear the words clearly; he raises his hand to his weakened ear. But he understands all the same. The happy smiles mark the birth of a new vase: the latest, perhaps the most beautiful of all. It’s standing there, on an embroidered tablecloth. It’s entitled Verde Serenella 18, but it might just as well be called Allegro Vivace, like the piece by that other deaf man, Beethoven.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

THE OBVIOUS SURPRISE

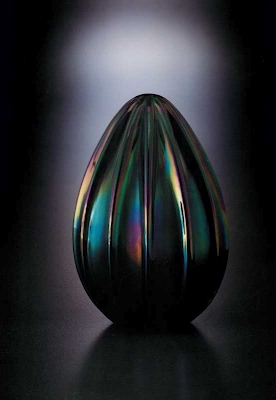

According to tradition every Easter brings an egg and, since 1982 Archimede Seguso has been giving his friends an Easter egg as well. Archimede’s eggs have also become a tradition, and the collector who gets one proudly puts it in his dream cabinet. This year, Archimede’s egg is extremely delicate: the colors are not mixed: there is only one shade of slightly pearly green that expands like a forest scent. There is no particular workmanship either; no semantic or esthetic ambiguity. In fact, it is one of the simplest eggs ever made, and yet, it seems to rise up, in flight like a balloon, supported by elegant ribbing.

Vase and bowl, green Verde Serenella 18, 1996. Vase and bowl with light ribbing along the exterior in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 15,5; h. cm. 31,5.

A sign of current tastes? Perhaps at least if it’s true that our tastes, headed towards the rendezvous with the year 2000 cannot but combine understatement and elegance, that is, classicism and nature. Today’s culture is saturated with various sophistications as well as ideologies. It aims towards the purity of the ogos. Yesterday the word was anti-classics, today we are talking about classicism again in art and other aspects of our lives,from design to clothing, to interior decoration. Archimede’s egg symbolically fulfills this need for biological equilibrium. It is and always will be an egg. in the perfect shape portrayed by Piero della Francesca in the sublime Brera painting. But it’s also an egg that reflects our era. As we said about the Verde Serenella 18 vases, we could say that it’s an egg which captures the sense of rediscovered nature in its particular green of sparkling liquidity. And so? It isn’t a matter of principles here but of eggs, Archimede’s egg and it has a name, Verde Serenella 18, and this name itself is a symbol of good and beautiful things.

Egg 1996 “Verde Serenella 18”. Egg, glassblown decorated with a light ribbing in green Verde Serenella 18 glass. H. cm. 12,5.