NOTEBOOK 10

The “La Fenice” theater, the interior in detail. The inauguration evening of the theatrical season 1966-1967. On the right of the royal box, in the front box, Archimede and Emanuela Seguso are seated.

PRESENTATION

THOSE VALUES

The motivations that give rise to a work of art can be many and varied, a wedding or a war, love or tragedy, prayer or protest. This was the case for Tiziano and for Goya, for Renoir and Picasso. So too, it can happen today: as indeed it happened for Archimede Seguso, this century’s greatest master glassmaker, having reached a point of vital achievement at 86 years of age. A shocking occurrence – the destruction by fire of the Fenice – touched him directly: indeed he experienced the drama of the whole city from close up as his home is situated only a few metres from the theatre. The hours of nightmare endured on the night of January 29th this year have been transformed into fragments of beauty: a series of vases that Archimede wished to name after the Fenice. Impressions, tongues of flames, densifying smoke, dazzling lights: but also an emotion which is renewed, that stays alive. We believe that art – true art – must be like this. Not coldly planned or mere intellectual Utopias, nor distillations of aesthetic principles: but rather the strength of sentiments. There was a time, perhaps, when sentiments were stronger because life itself was harder. Artists did not have film sequences or magnetic strips before them, but events of intense pregnancy: it is understandable that they were struck by them and tended to translate them indirectly into the mastery of their art. This too can occur again today. “Biological truth” remains the foundation of artist creation. The work of Archimede and the Fenice provides an example; and it can become an admonition to those who still believe in the values of yesterday as values for today.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

THE MUSEUM OF ARCHIMEDE

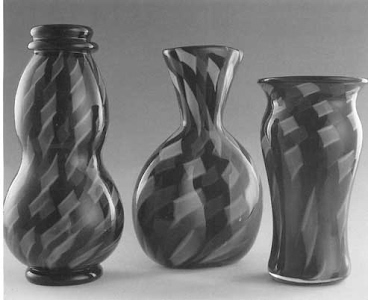

Vases and bottle “La Fenice”, 1996 Vase in transparent glass with oval section and black rim, decorated in the center with spiralling bands of white milky glass outlined in amethyst. h. cm. 29,5.

Vase with oval section in transparent glass, rim bent on two sides outlined in black, decorated with two “suns” with spiraling rays of white milky glass outlined in amethyst. h. cm. 27.

Bottle with irregular form in transparent glass, bent bottleneck outlined in black, decorated at the base with spiralling verticle bands of white milky glass outlined in amethyst.

h. cm. 28.

All types of glass mark the history of taste and the evolution of our art and trace our culture in motion: it means being “in time”.

What does a visitor generally search for in an art museum? One could answer: beauty. But this is an increasingly evasive concept today. Perhaps he searches for emotions: that is, something that responds to his sensibility, if not to his state of mind. He searches for originality in expression. He searches for the line of historical development in the sequence of the pieces. He also searches for (above all, I would say) the personality of each artist, with whom he can perhaps compare himself. That is what happens within each art museum: and therefore also in that extraordinary jewel-case of art that is the Archimede Seguso museum at Murano. One only needs to go in there, through the modest doorway on the fondamenta Serenella; climb the stairs along the red-carpeted passage; and find oneself before the display-cases and cabinets in which the great Venetian master glassmaker has arranged a selection of his production starting with the first years of the 1930s. There, before hundreds of pieces of glasswork of every kind, the spring snaps. Almost feverishly, the visitor seeks to quench his thirst. The eye does not know where to set its gaze; the mind flashes from one object to another; the hand would be tempted to caress one, ten, a hundred… I too enter the museum of Archimede. I notice a label, read a date: 1932. It seems to me the scent of a distant, almost mythical age. Some beautiful pieces of glasswork take me back to a certain historical “climate” that perhaps also constitutes a dimension of the spirit. A now famous piece goes back to that year: the “Donna con cerbiatto” (Woman with deer). It responds perfectly to the passage from Art Deco to the first years of the thirties: grace, elegance, but also the sign of a style. The line has a sinuous flow, widening the hips of the woman and charmingly narrowing the head. Could there be an echo of Arturo Martini? More than anything, there is evidence of a reference to a whole artistic movement. A little further on is Primo Camera, showing the muscular strength of a world champion (it is 1934). Sironi? Permeke? I recognize that Archimede is an artist, a sculptor: that is, he works at the level of the greats of his time. I am moved. I jump twenty or so years and come across a bowl of white filaments (1949), which plays on irregular, concentric lines, almost bizarrely so. And the other great season of informal-abstracts appears before me, almost transparently. There is Wols behind the door; there is Tobey. It is clear: Archimede is there, ready to collect the first fruits of the post-war springtime. Two years later (1951), the Dormiente (the Sleeper) resting upon a bench, forming a compact block of glass, and worked in perfect correspondence of masses in equilibrium. But of course, next to the rising Informal there was also the creative drive of a Moore (and, why not, of a Picasso). The two currents wrestle between themselves. And once again, Archimede is close by, ready to translate the evolution of tastes into works of art. This means being “part of the times”.

Vases and bowl, “La Fenice”, 1996 Bowl in transparent glass with turned down rim outlined in amethyst, decorated with curling bands in a spiral, alternating colors of white outlined with amethyst and coral outlined with white. h. cm. 14.

Vase with oval section in transparent glass, rim bent on two sides, second rim in milky green, decorated in the center with curling bands of coral glass outlined in white h. cm. 25.

Vase, oval shape in transparent glass, small opening with double rim in milky glass, decorated, in the center, with curling bands of coral outlined in white, interrupted by a handle. h. cm. 25.

I could continue along these lines during my visit. But for a real artist, this slipping into his era is not enough. One needs to translate his “historical antennae” into an autonomous strength of style. And so, wandering about this museum of optical and mental transparency, I try to find the essence of more than sixty years of work. Who is the “real” Archimede? I pose this question, with cold determination. Is he the extraordinary sculptor of solid-glass figures? Is he the subtle weaver of threads of the famous “lacework”? Is he the sumptuous colourist that mixes and changes tones until he “drowns” them in the glass mass? Is he the wizard of a fabulous technique that for decades has stunned people for its solutions? Is he the great creator of “bullicanti” or perhaps of the recent “green Serenella 18”? Is he the fascinating interpreter of the “breakdown”, both physical and psychological, of today’s society? Is he the marvellously lively craftsman of many “little animals” that seem to spring forth in each moment? Is he the renovator, as in the chandeliers, of the great season of Venetian Rococo? … I continue to ask myself the question. And fail to realize that every aspect of the production of this master is but a facet of an enormous prism that reflects everything. I attempt an answer: Archimede is like those artists (I immediately think of a name, mutatis mutandis Matisse) who go from a sinuous curved line to a dry jolt, from a soft tonal colour to a violent shade, from affectionate indulgence to the most instinctive gestures: and they do this always remaining themselves. I admit: I most like this breed of artists for the very reason that they do not conform to pre-fixed labels, they do not stick to a form of coherence at all costs, and they do not fall into mannerisms.

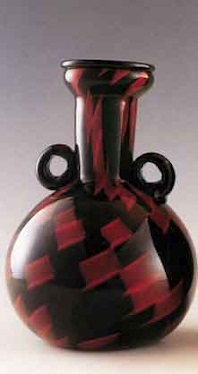

Anphora “La Fenice”, 1996. Round anphora with a cylindrical neck in black glass, decorated with red opaque glass confetti . h. cm. 27.

I like the “naturalness” with which Archimede Seguso attempts each solution: I can almost see it, in my imagination, while he moulds the snout of a fox that symbolizes slyness; or folds and refolds the incredible bands of lines that wrap the magical tranparency of a vase, or inserting, in the solid glass, shadings or iridescent pearly tones, or perhaps, trying to combine blown glass with solid glass (lightness and weight) in his bold dead Christ in a Mantegna-like posture. There is never -I realize more and more – that repetitive weariness that is so widespread in the mass-production of today’s tastes. I catch sight of the head of a French matelot full of lively sparkles in a small display-case: it seems to have popped straight out of a Jean Gabin film. And there, further on, is the green fox that I’ve already admired other times: it’s crouching in the grass, almost sniffing at the air. They are pieces from a long time ago, but they seem, together, to reflect their era and to step outside it. Could it be this “naturalness” that creates the background of “universal values” that must nourish a work of art? The bubbles inside a “bullicante” vase seem to almost move about: they are an invention by Archimede that made history, but they did not remain fixed in that time. The happiness of the execution has given that vase (to a hundred, a thousand vases) a vitality that flows away, leaps from the display-case, it fills me with a sense of euphoria, of joie de vivre. It’s wonderful to be in the company, even only for an hour, of an artist’s creations. The museum is not a trap or a cage for them. They are free to follow the impulse, the sensitivity, the mood of those who observe them, and almost caress them. My visit to the Archimede Seguso museum could continue. In the silence I hear the vibration (is it a noise or music?) of a bowl executed with incredible graceness. It trembles in my hands as though I were holding a small canary. The law of gravity is challenged. It weighs on me to lift the old green fox huddled in the grass, but it could suddenly leap out towards its prey. My gaze totters as I stare at the interwoven threads of a very fine lace. I realize that my sensibility has reached a peak. What do I search for in an art museum like this? I answer before leaving: I search for the rapture, the ephemeral rapture of something that is both fluid and solid, transparent and coloured, liquid and airy, real and unreal. I search for a reconciliation between opposites, the Utopia of unum. Is it hiding right there behind, or rather in, the glass works of this old and wise boy with the Greek name of Archimede?

Teatro La Fenice, Venice 1966.

Teatro La Fenice, Venice 1966.

CULTURAL NEWS

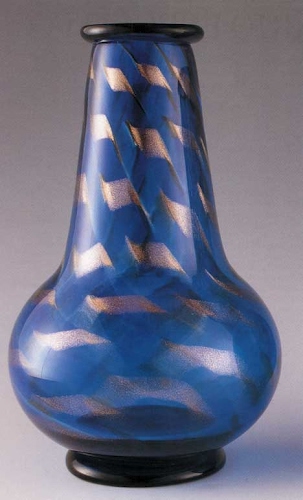

Vase and pitchers, La Fenice, 1996. Round glass vase decorated with blue curling bands with white opaque glass, double rim outlined with blue glass. h. cm. 27.5 glass pitchers decorated with curling blue bands with white glass, cobalt blue glass handles. h cm. 29 h. cm. 23.

THE VASES OF “LA FENICE”

With the drama in Venise the vases dedicated to La Fenice are born. They bear impressions, emotions, reflections and iridescence in the glass. A creative fire in the furnace took the place of the destructive fire. “We are safe and sound, but we’ve lost our theatre.” At the end of a dramatic night lived out by the Seguso family just a few metres away from the terrible fire that burnt down the Fenice, this was the bitter comment made by the wise Archimede. Together with other family members, the master glass-maker endured the darkest hours of his life on January 29th in the blaze of heat, smoke and flames that threatened his home, situated just ten or so metres from the walls of the Venetian theatre, separated only by an almost dry canal. Those scenes, contemplated in the anguish of feverish hours, marked an emptiness for Venice; but they also – as happens in the art world – provided Archimede Seguso with the idea of making a contribution, entirely his own, to the drama that engulfed the whole city. Thus, in the following days, some vases came into being, and then more and more over the following weeks and months, unique vases, each of them relating the impressions of the eighty-six year-old. The fire was – how could it be otherwise – the point of departure for this cycle of works entitled “Fenice”. Archimede is used to – he has always been used to – the fire of the oven: he has worked with it all his life. But the flames that he saw in those hours of the fire were different: a fire that involved him in his very fibre of being, threatening his home, everything that is dear to him – the furnishings, the objects of everyday living, the age-old customs, the glass works on the shelves, the books, records, knick-knacks, pieces of furniture caressed many times by anxious hands, the presence of family members, thoughts, dreams … All of this mixed together – if we can put it like that – with the memory of the horrendous scene witnessed from the window that night. Fire that burns, that does not purify, and, at the same time, fire that is also a liberation, even a sense of relief for a nightmare endured.

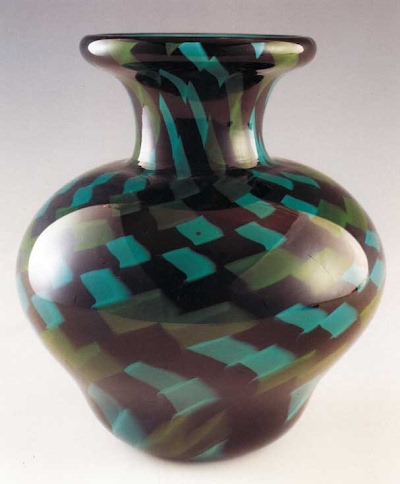

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase in black glass with long neck and crystal rim, decorated with harlequin colors of opaque white, yellow,red, blue, light blue and aventurine. h. cm. 27.

Vase in black glass with oval section and sinuous rim, decorated with harlequin colors of opaque white, yellow, red, blue, light blue, and aventurine . (Private collection) h. cm. 32.

Vase, oval shape, in black glass with flared, oultined bottleneck, decorated with glass “confetti” in opaque yellow, white, red, and aventurine. (Private collection) h. cm. 28.

Strange: it is not only the colour red – as one would think – that invades these new vases. There are also gleaming sprays of blues, yellows and whites. Venice dissolves in iridescence, in sparkling colours: just like St. Mark’s mosaics. The glass, in its transparence, absorbs and expells: in layers, strips, bands, sprirals, in patterns of patches, continual references, overlapping, and mixing. The tongues of flames rise here and there, flying away in their arrogance. It seems as though the lights superimpose one upon another: they are the reflections of the fire in the scarce waters of the canal. Archimede looked up, then below; and looking down he saw the leaping flames refracted by the rippling water. It is not coincidental that many of these vases are fragmented in wedges and flashes of light that repeat themselves, directed by rhythms dictated by air, wind and by the very whims of the fire. Confetti thrown high? Tongues chasing after each other in space?

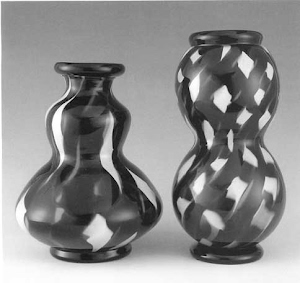

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase in black glass, round section and base, and two bottlenecks decreasing in size, decorated with curling bands in opaque light blue and white glass. h cm. 30.

Vase, cylindrical shape, in black glass with base and central bottleneck, decorated with curling bands in opaque light blue and white glass. h. cm. 33,5.

Taking a vase in hand, or moving it in the light, entering it with ones gaze, one gives in to the vertigo of movement, approaching it and distancing oneself, and perhaps ones gaze vascillates until it becomes softly blurry. And one ends up admitting: there is something of that Venice fire that builds up around and in the glass, an impression renewed, a shiver (or is it merely suggestion?) that takes hold. Archimede was there: looking out from the balcony, stubborn, eager to grasp, sensitively and intellectually, the vortex of a drama lived out just a few metres away, across the canals it became ever redder. We, by looking at these glass works of his, feel close to him: almost taking him by the hand, we accompany him in his fantastic journey. It is not difficult to fit these “La Fenice’ vases in the great sea of seventy years of glass production by a master like Archimede Seguso. There is a key to its interpretation: it is that of the rhythmic-dynamic aspect that has always been one of the components of his language. For Archimede, form has never been something static: he has never been a slave to cold geometricisms and modernist straining, that is, to merely intellectual parameters. We can look right back to the thirties to those solid-glass animals: true sculptures immersed in a vital “naturalness”. We look again at the “laces” and filigrees interpreted with rhythmic gestures which astonished the admirers of the informal art of signs from the fifties. Grace and harmony have always been united with an organicistic sense of form, even where the fine overlapping and iterations of signs seemed to mark the limit of a refined hedonism. That is to say: emotions have always prevailed. They prevailed even over the mastery of a formidable technique that Archimede has made use of without becoming a slave himself (and this is the point) to a “frozen style”. Certain herring-boned or meshed vases that have by now become a part of history, certain starred filigree bowls, bottles with coloured overlapping strips, wonderful “immersions” of fantasmagorical colours, fascinating alternating uses of opaque and clear, and perhaps those vases with feather upon feather, those beautifully soft opaline shades, that irregular, whimsical lace, or the lengthened drops, the amethyst points, the festoons, the gold-leafed shading, the polychrome circles, right up to the sparkling colours of the recent “Serenella greens”: all this, and even more, Archimede has brought to life with his natural happiness, with his harmonious sense of inspiration. So too for the “La Fenice” vases: with the transparent memory of something terrible as well, which has become an irreversible imprint, an indelible brand made during a frightning night.

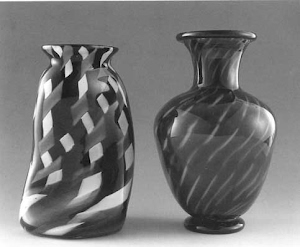

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase in black glass with outlined base and neck basin, decorated curling bands with opaque white and red glass. h. cm. 30,5. Vase, spherical shape, in black glass with base and rim, decorated with curling bands in opaque white and red glass. h. cm. 23,5.

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase with flared rim with crystal outline, decorated with two pairs of curling bands in blue/aventurine and black/opaque yellow glass. h. cm. 29. Vase, round with cylindrical neck and rim in black glass, decorated with two pairs of curling bands in black/aventurine and black/opaque yellow glass. h. cm. 26.

But it is clear: in art – in true art – even nightmares take on connotations of beauty: a beauty which is also life, nature renewed and perennial youth of the spirit. Certainly, Archimede is already of an age that one could define as venerable. The eighty year-old Tiziano flayed the poor Marsia with a dense and spirited painting, moved by the strokes of a nervous hand: and a masterpiece of new art emerged. In the oven, fire was superimposed to fire, becoming even “truer”, sublimated by that sentiment of universal time that purifies tragedy and gives rise to, according to Aristotle’s words, eternal life.

Vase “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase with bands in light blue glass and curling bands in dark blue and aventurine glass, base and rim in cobalt blue glass. h. cm. 30.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

EXHIBITION ITINERARY

Glass on the road: from Venice, through Montreux, Barcelona, Tokyo, the creations of Archimede Seguso to return to Venise in June in Palazzo Ducale with the Bestiary and in September for “Open glass.” Glass works travel. Fragile, transparent, almost gleaming rays of light, moments of enchantment: but also objects. They travel throughout the world. Archimede Seguso has them following a cultured itinerary, which leaves from Venice and spreads out here and there all over Europe, at times crossing the oceans.

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase in black glass with irregular surface, decorated with curling bands of white opaque shaded glass. h. cm. 29.

Vase, oval shape with base and flared neck in black glass, decorated with sinuous vertical filaments of opaque light blue glass. h. cm. 31,5.

The ideal point of departure for these weeks is naturally Venice. The city, although wounded by the Fenice drama, is returning to its cycle of life. The lethargic winter is over. In the elegant Frezzerie gallery, renovated with taste, situated in the heart of the San Marco district, the “green Serenella 18 vases” appear, with their sparkling lights, almost perfumed with dewy greenery. They stand out, together with a selection of the brand-new cycle dedicated – as we relate elsewhere – to the Fenice fire. On the other side of the Canale Grande, after the there is another gallery, the Micheluzzi gallery, at the foot of the Maravegie (Wonders) bridge. There, a hundred hand-chosen pieces are on display, going from the thirties to the present day: a triumph of filigree and lace, of external or “submerged” colours, of classical and whimsical forms, of blown or solid glass. Outside Italy, at least two appointments are musts: Montreux, in Switzerland, where the Chevalley gallery is hosting an exhibition significantly entitled “Musique, couleurs, formes”. Here too we find a hundred or so vases, old and new, which sum up the ardent, always inventive, path taken by this Venetian master glass-maker.

Vases “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase with round section and sinuous form with rim and base in black glass, decorated with curling bands in opaque yellow and red shaded glass. h. cm. 34.

Vase with oval section and flared neck in black glass, decorated with bands of opaque yellow and red. h. cm. 32.

Vase, lightly flared with protruding rim, in black glass decorated with “confetti” in opaque yellow and red shaded glass. h. cm. 26,5.

In Barcellona, once again the “Serenella 18 greens” and the “broken pieces” create interest among the cultured public of Spanish collectors: and it is the Biosca and Botey gallery which has them on display. More distant, much more distant, we find in Japan another selection of Archimede’s glass works, considered by local collectors to be of enormous value, in the Isetan department stores in Tokyo. But, ideally, how could one not return to Venice? On September 12th Archimede will make his rentree to Palazzo Ducale for “Open Glass”. It has been announced that there will be a big surprise. The “great aged one” never ceases to amaze.

Vase “La Fenice”, 1996. Vase in black glass with round section and lightly flared neck, decorated by two curling bands in double opaque color: white/aqua marine and yellow/green. h. cm. 24,5.

Vases La Fenice, 1996. Vasoin black glass oval, decorated with “confetti”in red and white opaque glass. (Collection Gianni Versace) Mis. h. cm. 32.5.

Bell-shaped black glass vase, decorated with “confetti” places checkered red and white opaque glass. Mis. h. cm. 29.5.