NOTEBOOK 12

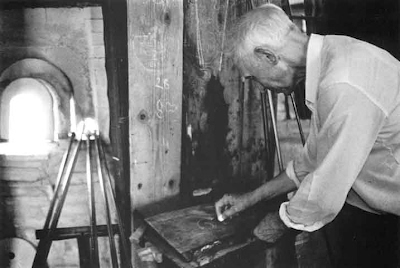

October 1996. Archimede Seguso working in his furnace.

A MURANO

Murano isola dell’infamia e del ricordo

isola d’acque e di lagune

isola antica e adolescente di desideri

nel tuo sogno segreto si schiudono fiori di vetro

vivono la gioia del tempo

Mario Stefani

PRESENTATION

HAPPY BIRTHDAY MAESTRO

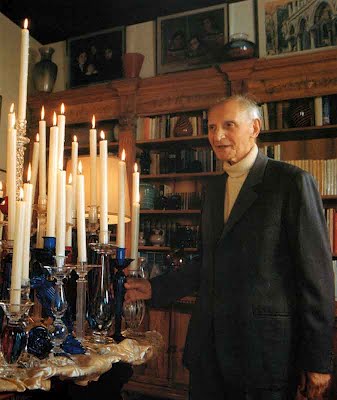

87 prototypes of candleholders created by Archimede Seguso for his 87 birthday.

This twelfth issue of the Quaderni di Archimede Seguso presents a testimony written by Pierre Rosemberg, of the Academie of France; a detailed study on the glassmakers and the art of glassmaking in Murano from Late 19th and Early 20th Century; a biography of Archimede Seguso, 87 years old on December 17th, untiring creator of techniques and shapes. He has obtained recently additional acknowledments and prizes. For the first time, in March, the Camera di Commercio of Venice has given Archimede Seguso a special prize for his activity as glassmaker, artist and entrepreneur of Murano. Last December, the President of the Italian Republic, Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, has assigned to Archimede one of the most important honors, the decoration as Commendatore for merit of the Italian Republic. All this rewards the man and his great art, that has reached far beyond the borders of his homeland. It is a message of creativity and ability in glassmaking from Italy to the world. Many international museums exhibit the masterpieces of Archimede Seguso. In Murano, in his furnace, where the maestro punctually goes each morning, creating each day new masterpieces; here, while sitting at his “scagno” (stool), shaping the luminous and incandescent glass to obtain figures and forms, he receives many visits from old and young admirers. Particular and significant is a visit of second grade schoolchildren: the young pupils have expressed, almost unanimously, the wish to became like Archimede “when they grow-up”. In this way, perhaps, Murano’s glassart endures in its more prestigious techniques and shapes. A wish for the Island of glass but a wish too for Archimede Seguso, who has made this art his main purpose in life.

CULTURAL NEWS

A VISIT TO ARCHIMEDE SEGUSO

Pierre Rosenberg, the French Academy, writes of his meeting with the maestro. Calle delle Botteghe on the opening of an exhibit of Venetian glass. The guests poured into the dark little alleyway. Rice fritters were being served. I noticed a handsome old man, slim and fresh, with a ascetic benevolent face. I asked around… It was Archimede Seguso. We were introduced, exchanged some words. I remember a firm, high voice, a Watteau character, slim and dreamy, a bit of Pierrot, a bit of Gilles. A few months later, on the island of Murano this time, I went to the Archimede Seguso glass works. Everything has already been said about Murano, mostly the worst, and quite unfairly. No tourists can avoid the compulsory tour of a glass factory. They are shown burning furnaces in huge sheds that look as if they are about to fall apart, busy workers, and they are told of an old tradition dedicated to… glass. Then they are taken into huge showrooms, brutally illuminated by fluorescent lights, where, room after room the diverse products of a centuries old craft interpreted in the most varied styles are lined up. Then, in every language they are pushed – according to their means, and according to their taste which is assumed to be awful – to buy… Murano is a flat, peasantlike island, far from the Venice of the canals and palaces. Urbane and businesslike, Venice has nothing in common with the industrious and rustic Murano. The charm of Venice, the charm of Murano, two worlds separated by a half hour of water, two worlds that ignore and turn their backs on each other.

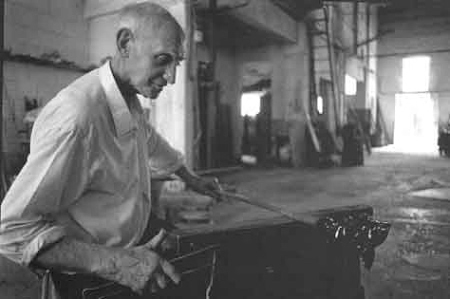

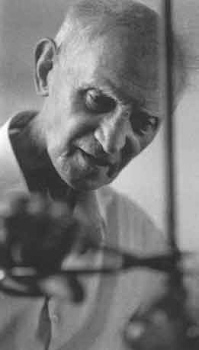

Archimede Seguso in his furnace creating an animal out of glass

Archimede Seguso is seated on a small wooden stool known as a scagno. He is surrounded by his assistants, each with a role, a place, a function, a level in the hierarchy of the glassworks. He is the worker bee. “What would you like me to make?” “A renard, a fox”. And then, the show begins, it lasts over an hour. A show that has often been described, but which is new each time, like the dawn. A soft, shapeless mass acquires form and color. Here is a thought, a demonstration would describe it better than many words: it would clarify, make it possible to visualize as we say nowadays… A fox by Archimede Seguso – in a beautiful deep blue – what is it? In this case, three elements combine in a single persona, the master, the creating artist of a style destined to evolve over the years, a glassmaker who transforms an idea into a shape, an internationally renowned factory. For a long time Murano has had great glassworks with international reputations, managed by great entrepreneurs who, as in the world of industrial firms have managed to sell to the extent that their products responded to the tastes of a public that they made every effort to cultivate and educate. In every era Murano has had its great glassmakers (whose names an ungrateful posterity has neglected to remember) who knew how to combine virtuosity and creativity, who knew how to use the technical processes in glassmaking and turn them to the advantage of their own skills. There have always been artists, sculptors and painters, architects or designers from Murano or who came from the mainland, even from the misty North, for whom glass has been a means of expression. Some of them – but their stories have yet to be written – were able to distinguish themselves by working better with glass than with stone or on paper. Others distinguished themselves… Sometimes the entrepreneur imposes his own vision, he discovers or outdoes the best glassmakers, he attracts promising artists, convincing them of the riches that glass can offer. Sometimes it is the artist who invents and creates, who molds the glass to his genius. Sometimes it is the glassmaker, gripped as in a vise, who combines the peculiar features of glass, of which only he knows the infinite possibilities, in his own way. It is to this subtle interplay of three elements – the factory, the glassmaker and the creative artist – that Murano owes its existence; it is to the changing equilibrium among these rival yet complementary forces that Murano owes the honor of never having lost its vitality. Le Mystere Picasso (The Picasso Mystery), the film by Henry Clouzot belongs to the common memory. On the screen we could witness the birth and development of what in the beginning seemed shapeless lines and curves. The artist was able to imagine – well before us – exactly what he was about to make. There was already order in what seemed chaos – to us. The same applies to Archimede Seguso’s fox. The synchronism of movements, the precision of each, the combination of practice that has nothing in common with the demeaning repetition of the assemblyline worker, and the expectation of the coming transformation amaze and fascinate. As in a ballet, we are suspended by every movement, we hold our breath – the accident, lying in wait is always possible… Archimede Seguso’s strong hands are still in control of the game. The maestro enjoys his work, work has always amused him, only work amuses him. Here is the fox. Why is it shaped like this? Why is it blue? The master ignores his surroundings. Here is the fox. Archimede Seguso has spent his morning well, another morning well spent, and now he goes off to lunch, with nothing in his hands, nothing in his pockets…

A sculpture depicting a solid cobalt blue fox.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

MURANO GLASS MASTERS OF THE XIX AND XX CENTURY

A dynasty of glassmakers, the Segusos, active since 1300, continues to mark the events of Murano glass. The leading figures in the history of Venetian glass, and therefore of its literature, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries are definitely the Segusos. Having handed down the art from father to son since the mid-nineteenth century, they are a rare example of a family that is totally and continuously engaged in glassmaking. It is precisely for this continued productivity and for being a historical, integral part of reality on the island, that they can provide an appropriate reason for describing the highly articulated context of the community as regards certain definite and sometimes neglected aspects.

Chandelier, of blown glass and made by hand, in amethyst glass.

The chandeliers presented here are part of the current production, in the late 19th early 20th century taste.

With reference to the “traditional blown glass”, the second half of the 19th century started rich in prospects even though the residue of the Austrian domination with all the economic burdens of taxes, European competition, and unemployment was still strong and present. The difficult moment of transition and instability on Murano was also captured by the Abbot Vincenzo Zanetti who, in 1864 at the opening of the 1st Glassmaking Exposition on the Island felt obliged to “urge the makers and craftsmen to save and improve the art [of glassmaking] as much as possible”, “their sole means of subsistence” by “repeating those items which since the Middle Ages nearly up to the fall of the Republic had astounded the most cultured nations”. This was, infact, the thrust for the late 19th century rebirth of glassmaking, aimed at making more or less faithful reproductions of old Venetian models, focusing on difficulty: “difficult for the more difficult.”

Archimede Seguso, for his 87th birthday, blows out the candles of 87 prototypes of candleholders created by him.

A great inspiration in those days was certainly the Museo di Murano, that opened in 1861 with its antique glassware, its books and the adjacent “Scuola festiva di disegno” that was supposed to “educate young people in glass making.” The general organization in the glass works remained unchanged, like the art of learning the craft itself, so that even in the 19th century the “glass-blowers” were making glass almost by “induction”. “They seem to have inherited by right the brilliant technique that made their ancestors famous”. The craft was handed down from generation to generation, almost involuntarily. But the hard work in the hot glassworks, and the long apprenticeships led to a “natural selection”. Boys who began as humble helpers or “garzone” at age 10 and had shown special aptitude for the art could be promoted to “servente” or first assistants to the “master glassmaker” – the maximum authority – by the age of 15. Regarding the merits and characteristics revealed through work there was and still is a true hierarchy, for titles and duties, with specific names. These titles affect not only the working world, but in everyday life as well. For example, the titles which have distinguished the Segusos over the centuries (and these are the highest honors) are “Gastaldo”, “Messer”, “Paron” and “maestro vetraio.”Getting ahead in the factory was not automatic. The glassmakers were not very well educated, even if true technical knowledge was in the hands and head of the master, who in addition to holding the ancient secrets of his ancestors, was greatly in demand. Creating a relationship of respect and trust with the master of the glassworks often led to the youth’s being able to work alongside of the master.

This was not the case for the other workers, who even during the “cavate” periods, that is when the furnaces were shut down for lack of orders or because of some decree, were “hired” by either one factory or another. They would wait outside the factories, on the bridges, for a job offer. Since the artistic glassware was primarily hand-blown Venetian style, the masters and “servente”, young or not so young, “local migrants”, had attained more or less the same level of preparation. It was for this reason that they could work for any factory without comprising the efficiency or quality of the products. There was competition, but it was certainly not caused by the movements of this skilled “migrant” labor force. Working hours were long and irregular; in some periods personnel was increased, without specific hours. Often the factories worked day and night with several shifts, sometimes the men worked up to 20 hours at a time, according to demand. Weekly wages were not at all high, and Zanetti himself complained that wages, even those of the masters, were too low. The health-employment situation at the end of the 19th century was certainly not the best. There were no real contracts to speak of, nor were there work safety programs to “protect human life, public health and public safety”. In this regard Vicenzo Zanetti complained that “the factories with the furnaces for working raw materials with blow-pipes., should be much better disciplined, since the enormous amount of poisons, nitrates, and sulfur they use spread a thick fog impregnated with deadly gases and poisonous molecules over the area”; and “innovations must be developed and put into effect, but not to the detriment of the poor workers, rather to their advantage; it is the entrepreneur who must determine how to obtain the greatest profit from his industry, but he should not decrease, but rather increase, if possible, the number of workers [he employs].” The typical late 19th century artistic items made on Murano were the very light, very elaborate blown pieces; they were difficult to make, filigree and zanfirico, with colored patterns to varying degrees; they were the mosaics, reproductions of Greek and Roman pieces, and bowls with goldleaf, graffito and glazed decorations. These 19th century “revivals” were made in very few factories on the island of Murano, including those of Antonio Salviati who, in 1866, was the only maker of “blown and old style filigree” glass. Giovanni Seguso and Antonio Seguso, who held the “record in the classic art of blown glass” were particularly active in this sector of Salviati’s production. The extra-fine pieces which drew “enormous praise” at the Universal Exposition held in the Paris the following year were made by these masters who received Honorable Mention on that occasion. At the II Glassmaking Exposition in 1869, Antonio Seguso, the “leading artist at the Società Salviati factory” again received an award for his “blown and free-hand” creations, this time it was the Gold Medal. In 1870 in addition to large, hand blown bowls, he began making vases with glazed decorations: here is an copy of the Barovier bowl. In the same year he received yet another award for his work at the Workmen’s International Exhibition in London.

Chandelier, glass blown and made by hand, in straw colored glass.

Another great contemporary artist was Isidoro Seguso who, in 1873, created an excellent replica of the famous Guggenheim bowl that had been loaned to the Island of Murano by the merchant, Michelangelo Guggenheim. In 1877 Antonio Salviati left the Compagnia Venezia Murano and founded the Ditta Salviati & C. Thus, the Compagnia Venezia Murano became the property of Antonio Seguso, his entire family (children, cousins, grandchildren etc.) and Vincenzo Moretti. In 1870 both companies participated in the Universal Exposition in Paris, and presented with glass that was so similar as to good taste, elegance and variety of pieces that it predicted a strong competition for the future. There were also reproductions of Greco-Roman vases made with the mosaic and twisted reeds technique created by Vincenzo Moretti and Antonio Seguso, the latter also made the copies of hot formed and cameo vases. Isidoro Seguso of the Compagnia Venezia Murano moved to the Ditta Francesco Ferro & Figlio. In 1892, participating in the Genoa Exposition, under the name of the factory for which he worked he presented a complex bowl, decorated with figures of seahorses. At the 1881 exposition in Milan, the Compagnia di Venezia-Murano di Antonio Seguso presented the “Phoenician vases” that were supposed to be the first interpretations of ancient, pre-Roman brittle-core vases. An item that can certainly be considered “Segusian” is the “adventurine glass chalice bowl”, dated around 1885, displayed in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague. The Segusos also made the set of drinking glasses that were given as a gift to the “newlyweds, Vittorio Emanuele and Elena” who were guests of the Seguso glassworks in 1897.

Chandelier, glass blown and made by hand, in a light green glass.

At the Glassmaking Exposition of 1895 the judges once again awarded Antonio Seguso, his sons and grandsons. The old artist was honored for the inspiration that he gave to the local art of the 19th century, bringing the “art from the Baroque and clumsy to the refined elegance of the sixteenth century”. The judges expressed enormous gratitude “because he succeeded in overcoming difficulties that seemed insurmountable”, he was cited as an example for future generations of young glassmakers, and the judges wished him “the right to rest after so much work”. The judges at the Exposition were deliberately very critical of the local glassware on display to highlight what, in their opinion, were the defects and “merits” of the winners with the sole purpose of safeguarding “good taste”, the only sure guide for works of art. For the occasion, other awards were given to: Giovanni Seguso, gold medal for “outstanding talent in blowing elegant and unusually light imitations of antique glass”; Liberale Seguso, received Honorable Mention for “good taste in executing some objects”; Isidoro Seguso received the silver medal for “some pieces made with much grace”. In 1899 Giovanni Seguso received the Cross of Merit in Nice. At the end of the nineteenth century, in 1896 to be exact, Gabriele d’Annunzio came to Murano to work on his notebooks for his novel “Il Fuoco”, that he completed in 1900. In addition to presenting the myth of Dardi Seguso, a character that D’Annunzio created and was particularly fond of since his appearance in other works as well, the book describes Antonio Seguso’s glass factory, his lean figure and the goblet that he presented to Foscarina, the heroine, along with Stelio Effrena of the book’s Murano setting. It is from his detailed descriptions that we can understand the almost “ritual” atmosphere of a nineteenth century glass factory which does not differ greatly from the one owned by his fortunate and illustrious descendant, Archimede Seguso. On the one hand we can glimpse and perceive the annealing furnace that is adjacent to the “melting furnace”, the “fiery breath” we breathe from the moment we enter the factory and the fragrance of the burning wood; on the other hand we can almost savor the silence of the factory that is broken only by the bustle of the workers, the burning wood and the sounds of the blowpipes. This taste for the historic, traditional Venetian styles would last until after World War I, when the Liberty or Deco movement began to blossom, unfortunately, this style never took root in Venetian glass production. Only in the nineteen twenties would the first substantial changes in Venetian glassware be seen, that once again began to play an important, innovative role in glassmaking on the international artistic scene. The first to work in this context in the early 20th century were Giovanni Seguso and his son Antonio. In addition to various awards they received at international exhibitions, they deserve credit for having made the Venetian glassmaking industry progress out of the slump it had been in because of overly strong ties to the past. The first “modernizations of the art” were created by them. Working in various firms on the island before the outbreak of World War I, in the ‘twenties they founded two of the few companies that finally marked the updating and modernization of the traditional Venetian-Murano style. In 1919-20, with ten partners Antonio Seguso founded the “Vetri Artistici Fratelli Barovier” glassworks. In 1929 the maestro left the company to take over a factory, in 1930, in Campo Cimitero with his sons Ernesto and Archimede. At the same time, in 1921, Giovanni Seguso became the “reference point” for the newly established “Cappellin Vanini & C”, in addition to the duties of master glassmaker, he was also the technical and designer. In 1925 he left the firm and with Cappellin established “Cappellin & C”. It is superfluous to say how much the personalities of these two masters meant to the fortunes of the companies for which they worked and which they owned. In fact, in addition to being partners, it was they who, with their own hands, created the glass items. There is no doubt about the importance of the entrepreneur’s role, since it he who directs the entire glass works, but we must not forget the important artists who are sometimes merely named in the literature. Sometimes they only have the merit of having resisted for so long at such a hard and demanding job, that is becoming increasingly anachronistic and “out of fashion.”

APPENDIX

BIOGRAPHY OF ARCHIMEDE SEGUSO

Archimede Seguso in a recent photograph taken in his furnace in Murano.

Archimede Seguso was born on December 17th, 1909 on the Island of Murano. A direct descendant of the Segusos who had been glassmakers since the 14th century, he inherited the secrets of this art that had made Murano and Venice famous ever since the days of “La Serenissima.” Archimede’s strong artistic personality was composed and complete from the early days of his career. In fact, he quickly outpaced the normal period of escalation in the traditional hierarchy of the glassworks: in his father’s factory he was substituting the masters while still a “servente” and became a “master” with his own space before he turned twenty. Endowed with a special aptitude for the craft, his work became his raison d’etre, his main hobby and his art. His genius and talent imposed themselves on the part with his technical innovations that made tastes and fashions in both color and shapes, and the accomplishment of the collector’s items since his pieces were always one-of-a-kind and unique. Both as designer and creator he has exhibited his pieces in the world’s most famous museums and they have fetched high prices at the major international auctions.

Chandelier, crystal and 24 karat gold. Current production, in the late 19th early 20th century taste.