NOTEBOOK 13

PRESENTATION

THE CONCEPT OF “VALUE”

The language of glass and culture in movement.

Divided Entity, 1994, sculpture from the “rotture” series, in cobalt blue, surrounded by crystal, cm. 29.

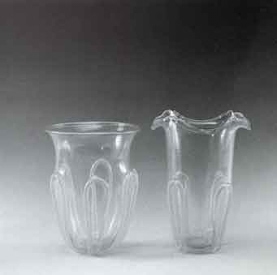

Above, a pair of gold oval vases decorated with six and four vertical ribs outlined in gold, cm. 25 and 2l.

A historian such as Le Goff has bitterly posed the question: “Can we still talk to each other?”. The crisis of values that characterizes this day and age, is also – and above all – a crisis of language. We all say the same words (such as liberty, justice, democracy), but in reality we are talking about different things. The same thing occurs in art. But art has inhabited such distant planets that they even have strange names: Minimal Art or Poor Art, Conceptualism or Brutalism. What we need is a common language, that is, we need to understand each other in relation to the fundamental idea of “values” that also encompasses “quality”, the constant guiding thread in Archimede’s entire artistic career. It is for this reason that the “Quaderni di Archimede” aim at indicating a key for interpreting Beauty: which is also a very precise syntax. We want to make our contribution to understanding Archimede’s glass. Glass is a material that can lead to art, like marble or oil paints. But it is not necessarily identified with art. Whoever uses it as a medium must bear inside a universal value. We are firmly convinced that Archimede Seguso, who will be celebrating his ninetieth birthday this year, is a bearer and disseminator of this value. His glass reveals art, revealing it to the point that it is understood by the most refined connoisseurs, and by anyone who thirsts for beauty. Today, we would like to talk about the cordonati [cordons] made from 1948 to 1950 and the rotture [breaks] created from 1994 to 1995. The two may seem diametrically opposed, and yet they complement each other: art as a solid compact structure and art as a painful sign of crisis. This is what Archimede Seguso means with the concept of “value”. In both types we can see the careful execution and manual skill, in accordance with the concept of “quality”. Archimede expresses himself though this language under the sign of eternal classicism, and makes it easier to understand each other.

CULTURAL NEWS

ARCHIMEDE IN THE MUSEUM

The rediscovery of glass in the culture of today: a dimension that has become historic. That widespread desire of Beauty present in an exhibition that is becoming more prestigious throughout the world. Poly-materialism is spreading through art today. In the sixties we talked about whether, for example, sculptures could be made using polyurethane foam, or paintings with rags. The barriers have come down. And so the materials which until yesterday were earmarked for the so-called applied arts have now acquired primary dignity. Glass is certainly one of these, becoming so dignified as to attract even the most refined admirers. Galleries and museums display and collect original glass just as bronzes by Moore or Pomodoro. “Noble” Venetian glass requires such painstaking and specific workmanship that it can only be entrusted to specialists. Great painters such as Picasso and Kokoschka tried in vain to become master glassmakers. They failed totally. And this is where the refined skills of an artist such as Archimede Seguso come into play. He is, indeed, one of the world’s greatest living artists who designs and makes his glass. In the early thirties, he made both blown and solid glass pieces of fire and sand, light and color, almost suspended in air, fluid and apparently impalpable. They were lighter than a Calder “mobile” or Melotti’s filaments. But they were also as solid as a “Pomona” by Marino Marini -just like the “Pomona” by Archimede. Thus, having overcome the barriers of cliches, glass art by Archimede has become a must, desired by the most knowledgeable and demanding collectors. There have been may exhibit, especially in the last few years. The memorable exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the show “The Italian Metamorphosis 1943-68” included glass by Archimede. And in the past few months, it is sufficient to mention the exhibits “Italienisches Glas” (Dusseldorf, New York, Sapporo and Tokyo); “Lyon Cite Exposition” (Lyon), Castello Sforzesco (Milan), and the triumphal entry in “Tiffany XX Century”. Archimede’s glass has been compared to ancient Roman glass in “Vetro vetri, preziose iridescenze” at the Museo Archeologico in Milan. Among other features, similarities have been noted, starting in the ‘thirties, with sculptors such as Martini or Messina; surprising coincidences between certain filigrees 1970-72 and the Optical Art of Bridget Riley or Vasarely, affinities with Minimal Art, or parallels with the most refined informal (such as Tobey or Tancredi). He never became a prisoner of any one style, he already revealed an extraordinary grasp of virtuoso technique, Archimede has always been there to connect with the salient experiences and trends of his day. This is yet another reason that museums and collectors have been looking at his glass for some time. Our era, so ambiguous and fake, so vulgar and trivial in its manifestations does feel a need for beauty, and for Archimede’s glass.

Table with three legs of amber and green solid glass, 1951, diameter cm. 79, h. cm. 76. A similar copy of this piece is in the Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto. On the table, a black vase with gold spots, 1951, shown during the exhibit Italienisches Glas, Murano 1930-1970.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

A HISTORICAL CYCLE

Pair of vases, in gold crystal with gold/green ribbing, 1949, h. cm. 28 and cm. 29.

The historic cycle of Archimede Seguso’s cordonati vases began around 1948; it was a memorable year. For Italian artists it was the year of the first Biennale after World War II, a leap into modernism. It is sufficient to note that the main awards went to Braque, Moore, Chagall and for the Italians, to Morandi, Carra and Mascherini. It was also the year of the elections that dissolved the prospects of a left-wing victory; it was the year that major impetus was given to rebuilding the country. Archimede Seguso did not participate in the Venice Biennale that year; he was very busy making lamps and chandeliers which, with his friend, client and business partner, Alberto Sciolari of Rome, conquered the whole world. The Italians were acquiring an awareness of their new role in Europe. And the most advanced art felt the electrifying bi-polarism between realism and abstraction, between a “modernized tradition” and a “strong avant-garde” sense. How did Archimede Seguso, who was only 39 years old and already a famous master glassmaker react? His production spanned the trends: in fact, it accentuated the participation in the esthetic and ideological ferment of that year. On the one hand he worked along the lines of essential geometry that brought glass to an extreme, formal rare faction to enhance its intrinsic purity, hence it fit into the Italian design at the top of the world so to speak (the Cisitalia became part of the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York). On the other hand, he leaned towards a sort of plastic solidity, a decisive intervention on the material itself to exalt its power. It was, a time of “rebuilding” in which tradition, according to Archimede, had to be the axis for future developments.

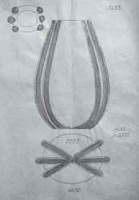

Bowl and vase in gold crystal with gold/green ribbing, 1949. Diameter bowl cm. 25, vaso h. cm. 28.

Bowl and vase in gold crystal with ruby shading and ribbings, 1949. Diameter bowl cm. 21, vaso h. cm. 25.

The cordonati which were to continue for another two to three years, therefore, fit into this argumentation. They are vases that someone defined as “masculine” because they are robust and basic, almost because of their (can we say it?) aggressiveness. The are characterized by cords or ribbing that are often twisted in ruby smoked gold glass or more frequently in green and gilded aqua. They comprise the “skeleton” of the base that opens like a plant with vague phytomorphic accents. We can almost feel the mass breathing in vital tension: an optimistic thrust, in the severity (that is virile) of the organic composition. Floral or even rococò ideas are overcome by the force vectors that thrust the fluid mass upwards.

Bowl and vase in gold crystal with green/gold ribing, 1949. Bowl diameter cm. 25, vase h. cm. 28.

Pair of vases in crystal and gold with petal shaped ribbing in white and pink zanfirico, 1949, h. cm. 27 and cm. 30.

The vases were quickly joined by the famous tables in different versions. They too were based on the defined cords and an oval or sinuous development of the tabletop. These tables, sometimes with crossed legs, were all different from each other, and they toured the world so successfully then to remain in the Corning and Kyoto museums. From the tables, the master glassmaker, designer and crafter went on to even more daring ideas, such as the furniture for the Barduagni store in Rome, or the staircase (still in 1948) that leads to the Murano showroom like a royal introduction. Hands rest on the glass banisters with trepidation; and the sensation is that of a living material that responds to feelings. In 1948, even Archimede, who was at the peak of his creative energy, participated in rebuilding the country. He was busy in the factory and active in expositions. His glass was greatly in demand and it was already clear that it would be sought after by European collectors. Then the important commissions began to arrive, for example, from Alemagna in Milan, for the Astra cinemas in Padua and Udine, for the Excelsior cinema in Milan.

Pitcher and glasses in gold crystal with green/gold ribbing, 1949, respectively h. cm. 16 and cm. 11.

Two bowls in gold crystal with green/gold ribbing, 1949, h. cm. 42 and cm. 35.

The Venice Biennale invited him to participate in the great exhibition of 1950 and a “sommerso” piece was sold for Lit. 2.500. Invitations poured in from abroad. The cordonati acquired primary importance: they responded to a need for psychological confidence and plastic strength: precious with gold shading and at the same time solid in their primary plasticity. He created a mythical nude female in black glass, he sold his glass in New York to Altman, and in Venice to Pauly, he made the chandeliers for the Teatro Verdi in Florence and for the Teatro Lirico in Milan, and for the Hotel Continental in Chianciano. When it is made by the hands of a true artist – like Archimede – even a glass vase can become emblematic in the history of society and not only in the history of esthetics.

IN THE SIGN OF THE TIME

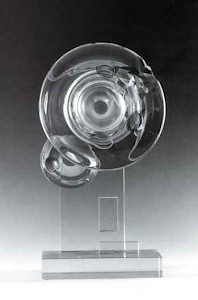

Scissione ritmica II, 1994, cm. 32. Polychromatic solid glass with areas moving away from the center.

Disjunction, 1994, cm.32. From the mass concentric glass shades in green with small blue off a fragment.

Like the “broken” series in 1994 have become a burning actuality. A fortunate cycle of glass pieces which express a state of physical and psychological laceration. Archimede is the interpreter of an age that seeks unity in the fragmentation. Archimede created the rotture about five years ago, in 1994. It was said then, that they represented “the tragic sign of our restless times”. The glass form, so violently shattered, revealed a sort of alienated beauty in the fragments. Something broken down and put back together – a tragic existential core – that developed from the meanderings of the psyche and turned itself onto society. The rotture became famous in a short time. They went around the world bonding the extraordinary fineness of Venetian glass with the individual or social problems that characterize the lacerations of our era. But what about today?

Intaglio di Carnevale, 1994, saturnian explosion of green, ruby, and blue bands, h. cm. 45.

The tragic events in the Balkans that have darkened this spring, once again confirm Archimede Seguso’s feelings and intuitions. The rotture, loved, admired, envied and requested more or less everywhere, have become a symbol of the modern condition; they are considered on a par with a prophecy. Artists, we know, often foresee events, they presage them and even recount them in advance. Ever since his youth, in the thirties, Archimede has been an interpreter of his times and not only a creator of exquisite, universal items. With the rotture he wanted to give life to a feeling that is both bitter and hopeful: the wounds are portrayed as such, but they also show signs of regeneration. After having worked his whole life (in 1994 he was 85 years old) at constructing, Archimede Seguso began to break, lacerate and shatter. He took his beloved glass, that was reduced to the essential purity of form wrapped in sparkling chromaticism and “violated” it. The fragments fell to his feet. He gently gathered them up and removing them from the chaos reproposed them according to the almost magnetic attraction that had been created. The vacuum became a sort of human breath, with the strength of miraculously healing the wound. Today, five years later, we can see these unformed forms with an even more intense eye. The message, both esthetic and symbolic, has grown; the metamorphosis fills us with emotion. That sense of pain seems to dissolve.

Eclissi, 1994, light green blown crystal scuplture, with straight and curved lines, h. cm. 55.

Spazialità, 1994, blown crystal sculpture, h. cm. 34.

Visione, 1994, Concave solid glass in light green with darker green shaded bubbles, h. cm. 55.

Will Europe, will the Balkans, will our country manage to heal the breaks and wounds inflicted by this tragic conflict? An old and venerated artist, like Archimede, says yes. The glass fragments put back together form a new type of beauty: ulcerated and painful, but more vital than ever. As we hear and feel the echo of the break, physically and psychologically, we also feel the sense of unity Plato’s “reductio ad unum” that compacts and re- composes, that bonds and unites.

LEISURE

An exhibition at the Conference Hall of Union Lido Cavallino Venice: Art comes in your spare time. Together with the cordons and with the “broken” series there is also “Hurricane”, the last egg of Archimedes. In church a solemn golden Nativity. There is something new: Archimede at the grandiose “Centro Vacanze Union Lido”, on the Venetian beaches. His glass walks along side leisure time. Archimede has occupied his life with his hobby, that is his work. Tourism needs art, in fact, it seeks it out during free time. And so, this unusual exhibition by the master from Murano will be held from July 7th until the end of August, in the Centro Vacanze that hosts over ten thousand guests, for a total of over one million each year – mostly from northern Europe and Germany.

Nativity with 12 characters in solid transparent glass outlined in gold, 1965.

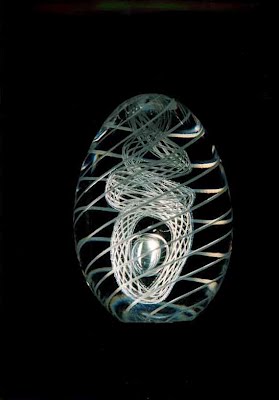

There will be two main sections: the cordonati made between 1948 and 1950 and the rotture from 1994-1995. They are two different, yet complementary aspects of Archimede’s production. Both, especially the former, have been historicized, and limited in production. The exhibit will be completed with two outside sections: a Nativity Scene, fifteen elegant clear and gold glass figures that seem to move with delicate sinuous rhythms (other Nativity Scenes by the master can be seen in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Madrid and in the church of Santo Stefano in Venice), and a selection of his famous Easter eggs. They are numbered for collectors, and the group on display includes the latest addition, “Hurricane”, made of transparent glass with interwoven white threads and a sphere. We know, the signed eggs are one of Archimede’s imaginative inventions and he has been making them for about twenty years: the symbol of fertility, this year especially, celebrates the master’s ninetieth birthday.

Details of some of the characters of the nativity, in solid transparent glass outlined in gold, made in 1965.

And finally, the exhibition will feature the pictures/glass/sculptures that Archimede has made in cooperation with Ferruccio Gard, the neo-constructivist painter – and this, too, will be another point of interest.

Abbandono, 1994, sculpture composed of two elements in crystal with bubbles and two green and blue threads, h. cm.34.

Over fifty years ago, in 1948, Archimede Seguso wanted to beautify the main staircase that led to the showroom in the Murano glass works. How could he do it? With glass, naturally. And so, the great master glassblower created the balustrade of a staircase with intertwined supporting columns made entirely of glass. Today the staircase, that has become a part of history, leads to what is now the Archimede Seguso Museum: a work of art among his many works of art.. Archimede Seguso, entrepreneur and master glassblower of Murano, like his Medieval forefathers, is the incarnation of tradition, technique, inspiration and skill. He is the figure who creates the link between the rediscovered craft of eighteenth century glass-making and twentieth century innovation. His generous spirit and disarming simplicity make him a truly charismatic figure. For a good part of the twentieth century Archimede Seguso has been the leading figure in avant-garde glassmaking. His works reveal technical studies that are often complex, but they are also linked to the formal quality and thus free of pure virtuosity. Creator and tireless inventor of unique shapes and techniques, his works can be found in many museums throughout the world and they are highly sought after by collectors.

Egg of the year collection: Hurricane. Egg 1999 made of crystal with interwoven sixteenth century muranese threads. Antonio Seguso.