NOTEBOOK 14

THE UNDERSTANDING

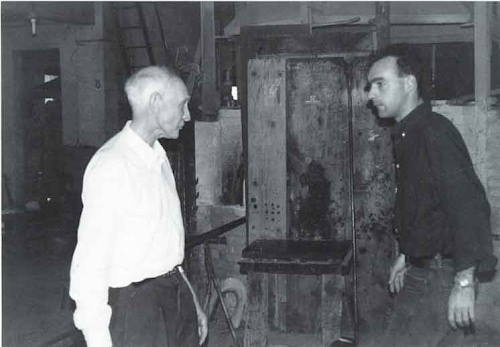

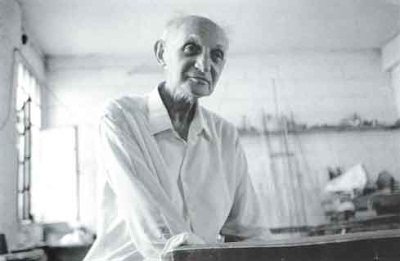

Archimede Seguso in his glassworks factory in Murano with his grandson Antonio.

PRESENTATION

At six o’clock in the morning on the 6th of September 1999, my father quietly left me. I spent the last twenty hours of his life with him. I had worked alongside of him since July 28th, 1958 and he was the lode star to which my compass always pointed. In his opinion, when I began working with him, I was always wrong. Then, suddenly one day, and apparently without reason, he approved of me and my work. He had educated and trained me so well that I began to travel onto his wavelength. When my training ended, my exciting real life began. It was always busy, with many difficulties and much tranquillity and filled with his mainly practical examples. He often said “Xe i fatti che conta” which means that it is the facts that count. I remember my father: bright, clear eyes, enchanting subtle smile, sweat pouring, confident movements, and his smacking kisses.

Gino Seguso

BUT HIS ART CONTINUES TO LIVE

Archimede Seguso, the heir of a great tradition and an innovator. Glass, the material which most challenges time. The secret of beauty made of light. “A walking encyclopedia of glass knowledge.”

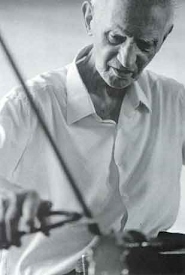

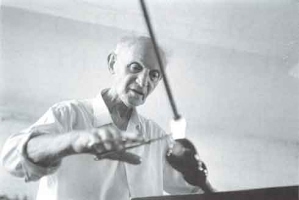

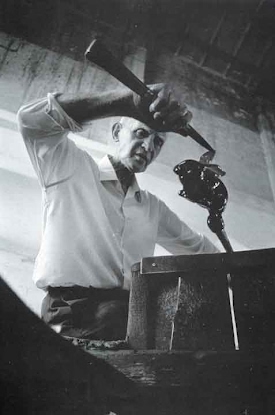

In these and in the following pages the maestro Archimede Seguso at work in his factory in Murano.

For Lord Byron every man’s life is like a grain of sand in the desert. But how many, today, like yesterday, leave something of themselves? The artist – the real artist – has at least this consolation: that something of him remains after his death. His works. The musician leaves a melody; the painter perhaps even only one picture; the poet at least a few lines of iambic pentameter. Archimede Seguso left glass: so many beautiful pieces of glass that could make an oasis in the desert. What a destiny for a piece of glass gently caressed by the hands of those who love and admire it? Glass is the material that challenges time to the utmost: in its transparency and purity it embodies the desire for eternity.

A few years ago in Milan, at the Archeological Museum, which is now in the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, Archimede’s glass sculptures were more or less compared to Syrian and Roman glassware from the I or II century AD. The public was astounded: that ring of essentiality, that quest for absolute beauty, that sensation of purity were the same in spite of the nearly two thousand years separating them. Anyone who knows how to blow or model glass, the way the great Archimede did with such skill in the Murano glassworks, does not fear the Angel of Death. He was lucky and blessed. From volcanic fires he was able to draw something intact that could withstand the challenge of centuries. His art will continue to live, and this is a consolation for us all. And perhaps it is a consolation for him, as we imagine him up there, among the clouds, smiling sweetly, the way he smiled all his life.

There is more. To the aphorisms of the “time great sculptor” (Marguerite Yourcenar), that is the fertile alliance between time and art, we must add something that only happens to a few artists. Archimede was (and we could say, still is) the scion of a long dynasty of master glassmakers. He was a direct descendant of the Seguso family that settled in Murano in the fourteenth century to give the Serenissima the equivalent of air and the light of the lagoon in glass. A French historian (and we will give his words below), Joseph Philippe wrote that “Archimede harmonized his entire life with glass making: heir to a great tradition he truly deserved to be considered “a living encyclopedia, the sum of all Venetian knowledge of glass.” I believe that it was a great thing for him to be part of a centuries-long tradition, like his ancestors who had given Venice one of her glories with glass. In the fifteenth century was Murano not the land of a dynasty of painters such as the Vivarini? And, in a certain sense, was not the art of glassmaking the successor St. Mark’s mosaics and the effusion of light-and-color of the great painters, from Bellini to Giorgione to Titian to Tiepolo and beyond?

The art of a great master glassmaker such as Archimede – the only one who actually designed and made his pieces without the help of designers or sketch-makers- can be compared to that of the “noble” arts such as painting or sculpture. Today, now that certain narrow ideologies have fallen by the wayside this is fully recognized. But then, ever since his boyhood, Archimede proved himself with glass sculptures, not only blown glass, but also solid pieces, leaving us objects that have been acknowledged (in writing) as parallels of the marbles or bronzes of Arturo Martini, Messina or even Fontana. He is no longer with us, but his glass – his creations – are in museums and collections throughout the world, especially in America and Japan. The lace or filigree pieces are considered the apex of an astounding fineness, like the sommersi or the intrichi that reveal the sparkle of a color that dissolves in the purity of the glass. Archimede was aware of all this. For some time, nearly ninety years old, he had been thinking of handing down his knowledge to someone who was close to him – in hand and heart. And this is the other great consolation, that let him close his eyes in peace. He found his true heirs in his son Gino and grandson Antonio. How wonderful it was in recent years to see the great old man guide the arms of his grandson in the suffocating heat of the glassworks to convey the secrets of his very personal “craft.” His life continues; there is no caesura, no hiatus.

For us Archimede Seguso signifies an era of splendor for glass, from the ‘thirties to yesterday. But he also signifies some that will continue: the sign, the guarantee of a fusion (that is truly inimitable) of the splendid tradition of Venetian glass and the inventiveness of a man who left his imprint on the history art. That grain of sand did not yield a bush, it gave us an oasis of greenery.

ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A CHILD…

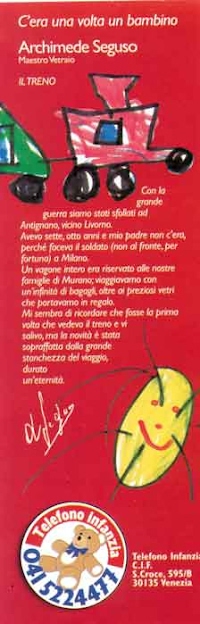

Archimede’s recounts his childhood games during the First World War. A calendar for the millennium, a moving memory.

Once upon a time there was a child… Archimede Seguso was a child during one of those tragic moments in our history: World War I. It was tragic mainly for the people of the Veneto region, and for the Venetians in particular with the war near them. The war was a tragedy that was taking place right there, around the corner. But how can a child stop playing? This past May, the Centro Italiano Femminile di Venezia asked Archimede Seguso to tell about his childhood games. He penned a delightful story that was published in a calendar, entitled “II giuoco…c’era una volta un bambino.” [The game…once upon a time there was a child]. The central theme is a train. What can a passing train mean to a child, especially a noisy, smoky train of those days? Next to his vivid memories in the calendar for 2000, Archimede put a crayon drawing of a train by a little boy, Edoardo Maria Nardi who is in the second grade in the “Marco Polo” elementary school in Portogruaro.

Here is the slightly childish, slightly nostalgic combination: the little boy and the old man are holding hands, looking wide-eyed at an enchanted little train.

The Train

During the Great War we were evacuated to Antignano, near Livorno. I was seven, eight years old and my father was not there because he was a soldier (luckily not at the front) in Milan. The families from Murano had a whole carriage to themselves; we traveled with an infinite number of bags and precious glass that we were taking as gifts. I think it was the first time I ever saw a train and boarded it, but the novelty was soon overcome by the tiring journey. It seemed to last for an eternity. We lived in a huge, even beautiful villa; but there were too many of us and so there was little room. Along with my mother, Maddalena, and my brothers, Ernesto, Bruno and Gino, there were my grandmother Girolama, my grandfather Francesco and my cousin Guido who had always lived in our house along with his father, Vittorio, aunts Alba and Cecilia, etc., etc.. I, a little boy from the small island of Murano discovered everything: the big street near the garden of the Villa Cume where soldiers passed on foot, with carts and animals, military equipment and very few automobiles; the railroad with the little station where the smoky and rare troop trains stopped; the inconveniences of moving. In our group of boys that ran like a flock of birds from one side of the park to the other, there was also Giovanni Ferro (a year younger than I and a cry baby) and some local kids. We played with terracotta marbles in a ditch in the middle of that wide street. Whoever went into the ditch and hit more balls won the game. Or we would feed the birds to see them close up and it was fun to have them peck at your hand with their beaks for a few crumbs. The winner was the one who fed the most birds. Suddenly, a train’s whistle would call us all to the tracks, we would run and follow the last, slow car and pass it just before the station. One at a time the windows would open and we would try to trade our marbles for a sandwich, or molasses candy or a few pennies with the passengers. Then, my grandfather, Francesco, fixed the paths on the grounds of the villa and we would gather all the dead leaves and put them on his cart and then play by ferrying each other from one place to another. The loser was the one who tripped when pushed. Our knees were always scraped and bleeding, and our cheeks were red, but our eyes, hearts and lungs were filled with joy, excitement and happiness.

Archimede Seguso

Venice, May 3, 1999

Details from a page of the Calendar 2000 made by the Centro Italiano Femminile di Venezia, with text by Archimede Seguso “Once upon a time there was a child…”.

Photograph from the twenties. In the last row, in the center, on the right of the boy with the black shirt, the Seguso brothers, Ernesto and Archimede.

AND NOW, IN THE HEART OF MANHATTAN

Archimede in the museum, his place is there. One hundred glasses: a long retrospective. A duck, a Bullicante, a submerged, lace: where everything becomes sculpture. From the solid to the blown glassline: form, sign, color. Is it true that Italian artistic treasures are discovered in America with greater interest than anywhere else? There are many symptoms that lead us to believe so. American museums are filled with Italian art, both old and new, increasingly more modern pieces. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the world’s greatest, displays the best of Italian design, from the red Cisitalia of 1945 to the everyday items from the fifties and sixties alongside of works by Boccioni and De Chirico.

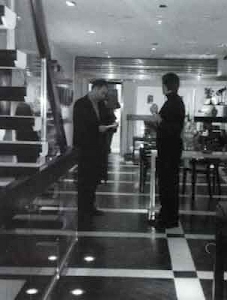

Antonio Seguso and Richard Mishaan on the day prior to the inauguration of the showing at the Homera Gallery Manhattan.

Archimede Seguso’s glass art is next to these by now “antique” and yet unequivocally “modern” items. It just takes the results of an auction, for example the nearly ten million dollars for “Primavera nelle Alpi” by Giovanni Segantini to rekindle attention. And today, the glass sculptures (even a filigree vase is a sculpture) are the focus of attention in the United States where many glassworks have been opened on the model of the refined Venetian tradition. Several times in these Quaderni we have talked about “Archimede in Museums”. Now the pieces by the master glassmaker from Murano have become historic: museum directors and collectors compete for them; exhibits are opened even in official contexts, especially when the aim is to demonstrate the historical continuity of antique, Oriental or Roman glass, with current items from Murano. Here in Manhattan, in the heart of New York there is an exhibition dedicated to Archimede Seguso – the first true retrospective exhibit since his death – that features about one hundred valuable pieces made between the ‘thirties and the ‘nineties: over sixty years of evidence of an art that grew under the banner of the purity and transparency of that most noble material, glass.

Vase, log style, Bowl, “bullicante” and fish, 1937. Vase and bowl in green solid glass, covered by six layers of “bullicante” crystal with goldleaf. Measures: h. cm. 29; h. cm. 11.

Ducks, 1937. Two green corroded ducks. Measures: d. cm. 30; d. cm. 20.

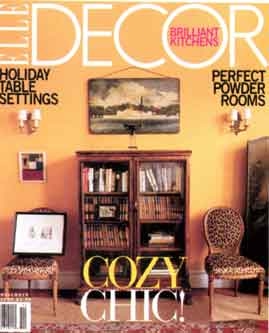

Here, on these pages we present an article written by Judith Nasatir, New York art critic, for the American edition of the prestigious magazine Elle Decor. In the essay she repeats parts of a conversation she had with Archimede Seguso in Murano, words are almost prophetic, especially when the old master hands the torch, so to speak, to his grandson Antonio, with the words “now, do better than your grandfather.” We wish to emphasize this touching moment.

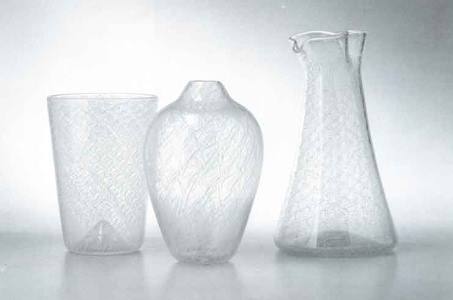

Vases “merletto” lace, 1952. Three “lace” vases decorated internally with a white netting design. Measures: h. cm. 20; h. cm. 22; h cm. 29.

Ball with bands, 1953. Vase, spherical shape, gold and white glass decorated intemally with spiral aquamarine colored bands. Measures h. cm. 15, diameter cm. 16.

The Manhattan exhibit is, in reality, a summary of Archimede’s work. It is important to remember (and to publish) some of the pieces on display precisely because they are so indicative of a historical pattern of development. They begin with the nineteen thirties. Here are two ducks in green glass: examples of solid glass sculpture that already fascinated the young Archimede alongside of classic, blown pieces. From the same period is the bullicante vase in pure green, that reveals the typical style of the decade, synthetic and solid, but at the same time free of the phytomorphic references. Then, from the early fifties, the famous “merletti” where the fine filigree winds in bands, curves and scrolls in a sinuous rhythm – authentic masterpieces of a modern interpretation of eighteenth century rococò. Then we come to the “sommersi”, the “losanghe”, the “Pierrots” and recently the “Carnevali” and the “Intrichi” where color shines in the most astounding shades.

There are also small vases: jewels in opaque or transparent glass, solid or light, feathers or coral, ivoried or gilded, in ribs or lozenges, ribbons with embroideries or brushstrokes, overlapping colors, starry filigree, onions, or optical, herringbones, mesh, reeds, sparkling reflections, all patterns from the mind and hands of Archimede. Mostly “blown” pieces, but some are solid, that is all glass, like the recent “Rotture” that are so symbolically expressive, or the gilded Arcamede.

Where does the tight-rope walker’s skill of the master glassmaker end and the pure creations of the artist begin? Perhaps in America more than in Europe there is an appreciation for the bond between manual skills and artistic creativity. They are two poles that the avant-garde of the last century separated, but today they are together in a blissful contrast. The success of the exhibit at the Homer Gallery in New York, that will be open until April is the proof.

Vase and bowl, black and white pattern, 1958. Vase and bowl with decorations in black and opaque white glass. Measures: h. cm. 29; h. cm. 11,5.

Vases and bowl, “crumpled”, 1952. Vases and bowl, ivory with gold. Measures: I. cm. 25; h. cm. 15; h. cm. 26.

Vase “merletto”, 1952. Vase with small cylindrical bottleneck decorated with irregular netting design. Measures: h. cm. 50.

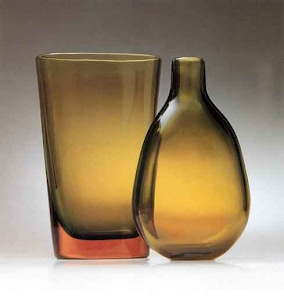

Submersed Vases, 1955. Vases with three layers of amber, green and crystal glass. Measures: h. cm. 31; h. cm. 30.

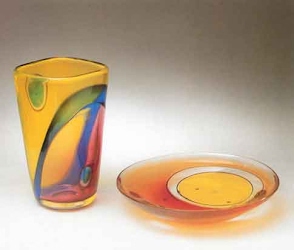

Other examples of pieces on exhibit at the showing in New York.

Vase and plate “Carnevale”, 1989. Vase and plate in blue, ruby, and yellow glass. Measures: cm. h 34; I. cm. 39.

Vases “Intrico”, 1994. Blue vases decorated with irregular milky threads and coral glass. Measures: h. cm. 32,5; h. cm. 21.

ARCHIMEDE’S PRINCIPLE

Seductive Seguso glass is a family affair. While he may no longer be able to yell out “Eureka!” every time he invents a different way to manipulate molten glass into art, nonagenarian glassmaster Archimede Seguso still thrills at the challenge of the furnace. As he says, “My favorite piece is the one that I am going to make tomorrow. The beauty of creating is to think of a new shape, a new way of working, a new techniques, a new piece.” The proof of that axiom can currently be seen at Homer, a Manhattan home-furnishings gallery that is saluting him with a show of his works through the end of the year. Seguso, who founded his namesake Murano-based glassworks in the late 1940s, carries on a family tradition dating from the 14th century.

“When I was 12 years old,” he says, “I used to have lunch with all my family, including my grandfather Giovanni, who was considered one of the best at making very thin glass in the old Venetian style, and my father, Antonio, who was one of the great masters of Murano.”

Seguso himself has originated countless innovations in form, color, and technique. During the fabulously fertile ’50s, he developed such recognizable, and collectible, designs as lace vases and experimented with surface patterns ranging from feathers, spots, and lozenges to black-and-white ornament, ribbons, and brushstrokes. The Homer exhibit also touches on earlier and later works to document the creative continuum. Progression, like the furnace, remains on the master’s mind. “Going in the furnace is exciting because I love to work with glass to find its possibilities,” Seguso says. “This is the same feeling my grandson Antonio has. I hope he will be able to surpass his grandfather.”

Judith Nasatir

AS GLASS SCULPTURES IN HISTORY

A great Belgian scholar remembers Archimede in an essay on “Ateneo Veneto. The style of the twentieth century interpretation in an original manner. The definition of “master of masters” is justified.

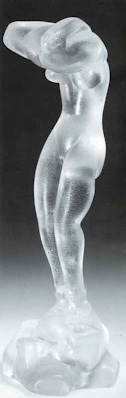

“Donna che si spoglia” (Woman undressing), 1934. “Bagnante nell’atto di spogliarsi” (Bather undressing), in corroded glass. h. cm. 30.

The bibliography on Archimede Seguso is enormous. Not only experts on glass, but art critics and historians have written about him. Now, there is an essay by Joseph Philippe, president and founder of the International Association for the History of Glass, former director of the Museum of Lieges and professor at the University of Montreal. In the last edition (n.36) of “Atti e Memorie dell’Ateneo Veneto” published by the prestigious Venetian cultural institution, Professor Philippe wrote an important essay on the “Principality of Liege and Venetian Glassmaking” describing the centuries-long relationships between the Belgian city and Venice. As we know, since 1959 Liege has been the home of the Glass Museum, featuring exhibitions of ancient and modern glassmaking – and recently a splendid exhibit on sixteenth and seventeenth century Venetian glass. It is significant that in an historical context, the Belgian historian dedicates considerable space to Archimede Seguso in his essay, recalling the title of “master of masters” that was given him by Giuseppe Cappa. Among other points, Joseph Philippe recalls how, since the late ‘thirties Archimede established himself as a sculptor of glass. His mode of expression – he observes – was never limited to any one specific aspect of modern esthetics. For example, in the thirties he interpreted the “twentieth century style” in his own, original way: plastic solidity and sculptural synthesis. Regarding the ‘fifties, the scholar mentions the interest that Seguso’s works aroused at the Biennale exhibitions: for example an iridescent female nude embedded in clear glass (1950), a large glass sculpture “colored in sheets” (Biennale, 1966) like a mosaic in a steel and cement structure. “Tireless searcher”, Archimede is defined as a complete master of glass sculpture: both designer and maker of works of such outstanding technical and esthetic quality” as to bring honor to the universal world of glassmaking with his many creations.

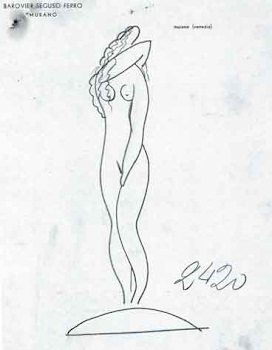

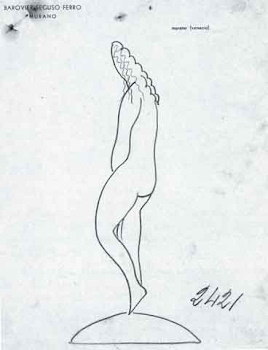

Two drawings of women, made by Archimede Seguso in 1932-34.

Regarding the title of a 1972 show in Zurich, “Kunstoder Handwerk”? [Art or Craft?] Joseph Philippe replies: “It is the works themselves and the class of he who made them that answer the question. There are no major or minor arts. Some pieces that can be defined in the domain of decorations outclass others that enter the so-called domain of the plastic arts.” In fact, the scholar says that the “the great artistic milestones of the centuries are those which, in the field of decoration is not limited to the craft stage.” This is the starting point for Philippe who recalls how Archimede Seguso, is at the apex of the art of glassmaking that is on par with the finest paintings and sculptures of the century.

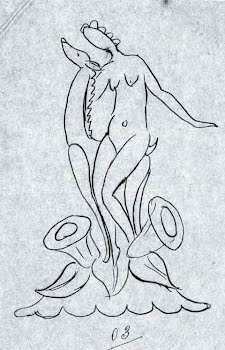

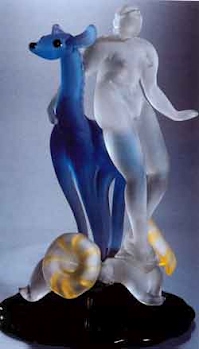

Drawing of “donna con cerbiatto” (woman with deer), made by Archimede Seguso in 1932. Next, Donna con cerbiatto, 1932. Figure in transparent acid treated glass with blue deer. h. cm. 23.

NEXT TO THE GLASS OF 2000 YEARS AGO

“Magic transparency” in Genoa: Archimede was marked as the Roman vessels. An eye whose objective is ideally towards the future. The power to compete with the past. Putting Archimede Seguso’s glass alongside of I to II century AD Roman glass has become symptomatic. There is something, beyond the technical, that unites the two millennia in the name of a quest for purity, beauty and functionality of the item. After Milan, Genoa will be the venue —until March 15th- of an exhibition entitled “Magiche Trasparenze” (Magic Transparencies) in which glass by Archimede is a support and almost a counterpoint to the glass items found during an archeological campaign at the site of the ancient city of Alcingaunum, the Albenga of today.

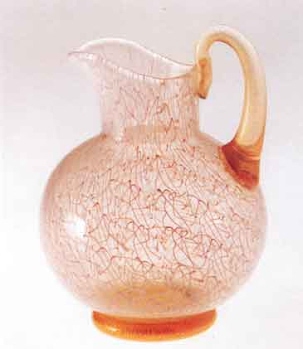

Pitcher, 1954. Pitcher in pink “lace” glass, ring shaped base and cane shaped handle in crystal and gold. h. cm. 17.

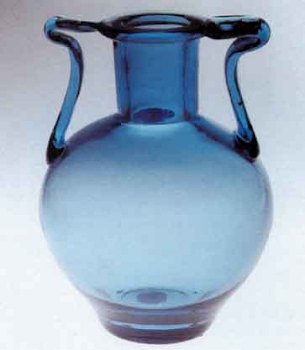

Amphora, 1990. Turquoise blue glass, ribbon handles. h. cm. 29,5.

This exhibition, as we read in the catalogue, puts the accent on the extraordinary, almost alchemical and hence “magic” procedure of transformation that takes a heavy, opaque material, silica and turns it into a pure, shiny, almost incorporeal material: glass. The glassmaker’s experience does indeed resemble that of the alchemist. In his workshop, similar to a mysterious laboratory, the glassmaker prepares secret recipes, handed down from father to son, in a continuous search for inimitable colors and transparencies. Drawing inspiration from the archeological discoveries at Albenga, the exhibition features many glass items that are unusual in their variety and rarity, to offer the visitor a fascinating journey through the world of Roman glass. The ancient shapes and iridescence enriched by creations by the artist and master glassmaker from Murano, Archimede Seguso, still reveal the exhaustible vitality of the art of glassmaking and the line of continuity between the ancient and contemporary worlds. And so, next to flasks, spoons, perfume bottles, vases and tear vials – everyday items in ancient Rome – and a splendid 41 centimeter diameter blue plate with inlay decorations, a rarity among Roman items, both antique and modern at the same time. There are some creations by Archimede such as a precious hand that seems to have been made to hold the small items from two thousand years ago. Here, Archimede tested himself in imitating Roman glassware, in “purpose” as well as “themes” for patterns. It is proof, above all, of his versatility as well as his respect for the art of antiquity. Is it not impossible to think that the art of the XXI century could not learn from Antiquity? Archimede drew his last breath on the threshold between two millennia. But, in ideal terms, he went beyond, towards a future in which the art of today must measure up to comparisons with the art of the past.

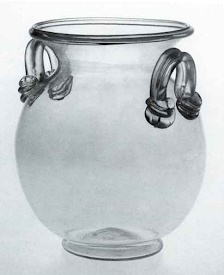

Jug, 1999. Jug with lid in varied glass with ribbon handles. h. cm. 26,5.

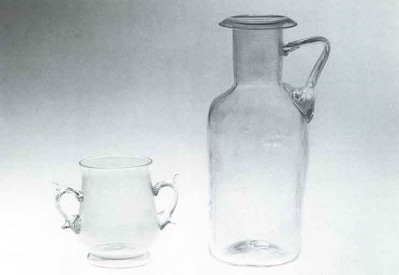

Kantharos and bottle, 1999. Two-handles glass in varied crystal, ring shaped base, ribbon handles. h. cm. 9. Bottle in varied glass, ribbon handles. 21,4.

THE BESTIARY, AREA OF FANTASY

For “antique Romagna” a retrospective show of glass sculptures depicting animals: from the baboon 1931-32 to the recent “golden Arcamede”. Jungian interpretation and the testimony of Giorgio Guardigli.

Baboon, 1931-32. Baboon sculpted out of light green solid glass. h. cm. 12.

“Arcamede dorata”, Cavalli, 1994. Four horse heads, gold and crystal solid glass. I. cm. 60.

The famous glass animals comprise a separate chapter in his long history. The first date back to the ‘twenties when the young apprentice master tried to abandon the routine of the neo-eighteenth century tradition to try his hand with true sculpture in glass. An exhibiton “Archimedes menagerie” was held in October-November 1999 in Forli as the highlight of the “Romagna Antiquaria” show. Prestigious items, were seen, admired and jealously requested by the major collectors, such as the “Baboon” 1931-32, the “Green Fox”, 1937 (that was shown at the Biennale of 1938); the bullicante Fish, also from 1937, and then the “Black and White Bear”, 1951; the festooned “Pigeon”, 1954 to the famous clear and gold glass “Arcamede dorata” of 1955. Obviously, these are all one-of-a-kind pieces, sculpted from solid glass.

Sparrows, 1955. A pair of sparrows in green and ruby shaded opaline and gold glass on a “bullicante” submersed base. h. cm. 14.

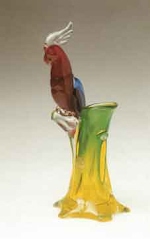

Parrot, 1957. Parrot on a tree trunk shaped vase in submersed glass, yellow with green shading and red with blue shading. h. cm. 36,5.

How can we interpret this enormous “menagerie” that Archimede created over the course of more than seventy years? The interpretation can even be related to the Jungian subconscious — as the critic and collector Giorgio Guardigli has done. In the animals the artist seemed to rediscover his childhood, that is youthful flights of fantasy. The bear, for example, is a recurrent theme in his creations. Symbol of wisdom, loyalty and strength, proud and generous, reticent and yet available, the bear knows how to control his emotions. But above all, there is that extraordinary ability for cyclical renewal, proof of an inexhaustible creative energy. How is possible not to see an “identikit” of Archimede in the hear?

In the following pages Giorgio Guardigli’s fascinating interpretation of Archimede Seguso’s “menagerie.”

Pigeon, 1959. Pigeon in alabaster with blue shading. h. cm. 37.

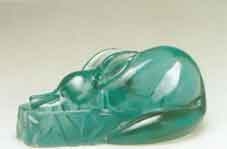

Green Fox, 1937. Fox crouching in the grass, slightly corroded solid glass. I. cm. 39. Sculpture presented at the Biennale of Venice in 1938.

Archimede Seguso’s menagerie is a world in which the master’s inexhaustible imagination moves freely. It is an improbable, yet entirely natural world because it is clothed in a fairytale atmosphere. In fairytales time and space are mobile and elastic. Anything can happen; everything does. Glass is the accomplice, a material that with its colors and effects offers thousands of opportunities for expression. These opportunities, however, are granted only to the great masters: those who are capable of taking that extremely fragile material to its extreme limits without “violence.” And until yesterday, Archimede was definitely one of the best in this limited group.

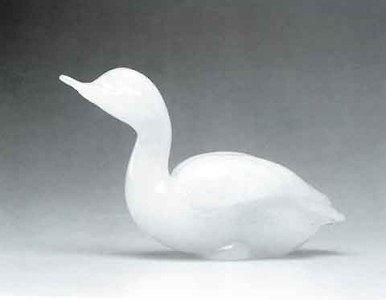

Duck, 1933.Anatra in white pulegoso (spongy appearance) glass. I. cm. 33.

Dog, 1968. Dog shaped bottle in smokey alabaster. h. cm. 28.

Archimede Seguso’s animals are “caught” almost by stealth in their most natural movements. They move and almost speak through their poses and expressions. And Archimede talks to them, modeling the material to their “words” in a dialogue that lasted a lifetime. Two elements emerge as we observe his creatures. The first is the plasticity of the forms. The second is the autonomy of the colors with respect to the subject. Plasticity for Archimede did not only want a return to order, recall to the “craft”, but also – and mainly – there was a strong need for inner harmony. And it is this need that makes us accept as natural the expressive power of the colors, that no brush stroke can change and all the elements are illuminated by the same light. Color becomes one with the shape; it seems to offer itself as essence of the body, letting us feel the presence of inextinguishable energy. Nearly always made of a single mass of glass, with soft, uninterrupted contours, Archimede Seguso’s animals are unmistakable for the fluidity of the surfaces, the equilibrium of the proportions, the naturalness of the movements, and mainly for the expressions that are filtered through a vein of subtle and amusing irony. Each time the techniques were a tour-force of difficulty and refinement, but the perfect execution was never virtuosity for its own sake and almost always took second place, nearly overpowered by the creatures’ enormous power of expression.

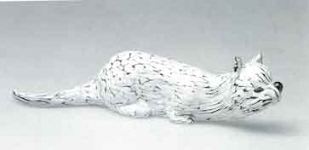

Cats, 1951. Cats, black solid glass with white enamel spots. Measure, respectively, I. cm. 19 and l. cm. 32.

Cats, 1951. Cats, black solid glass with white enamel spots. Measure, respectively, I. cm. 19 and l. cm. 32.

Archimede’s animals recall a primitive innocence. And the quest for innocence, beyond any bloody and merciless dimension to which history seems to reduce itself, is certainly one of the inspiring principles of Archimede Seguso’s lifetime work. The “Arcamede dorata” is both a symbol and message of this theme. Observing the fluid lines and sparkling golden beauty of the these animals, arouses a feeling of fullness and peace that can compensate the area devastated by crisis. It is as if by retreating from today’s chaos Archimede would take us to see the source of the myths. But how can this idyllic world reconcile itself with the lacerating and painful message of the “Rotture” that Archimede conceived almost at the same time?

Bear, 1951. Bear, black solid glass with white enamel spots. h. cm. 41

A man of sometimes long-suffering experience, Archimede could not bond with the painful evidence of a world torn by violence and “disorder.” He, whom the circumstances had forced into adulthood before his time, remained an eternal youth, filled with joie-de-vivre and optimism. The serene families of animals that he surrounded himself with express his profound spiritual harmony. When he reached the end of his time on earth, Archimede chose his grandson Antonio as the heir of all his experience and knowledge. Antonio practically lived in symbiosis with Archimede during the final years and received from the master, not only the secrets of his unparalleled techniques, but also the humanity and faith in the fundamental values that had made him not only a master glassmaker, but a complete artist.

Giorgio Guardigli

Duck, 1968. Bottle in the shape of a duck, coral and green shaded alabaster. I. cm. 35.

Fish, 1968. Bottle in the shape of a fish in coral and green shaded alabaster. I. cm. 33. Both pieces were made for a well known liquer manufacturer “in collaboration with the painter Luciano Forlan”.

“Arcamede dorata”, Ducks, 1995. Group of three ducks in crystal and gold solid glass on a sinuous base. I. cm. 38.

Guinea Fowls, 1955. Pair of guinea fowls in blue and ruby shaded opaline and gold glass on a “bullicante” submersed base. h. cm. 20 and cm. 16.

NEWS

From top to bottom: Archimede Seguso between his grandson Antonio and his brother Angelo at the furnace, while toasting the “Maestro” for his eightyninth birthday, on the 17th of December 1998. Jean Paul Lusset, director of the Teatro dei Celestini, with council members Andre Marechal and Denis Trouxe of the city of Lyon at the inauguration of the showing of the “Merletti” exhibition of Archimede Seguso. On the right, Gino Seguso with Mrs. Eva Barre. Gino Seguso accepting from Senator Cornelio Bucar in Sibiu, in Romania, the nomination of Archimede Seguso as member of the Academy of Traditional Arts.

Antonio Seguso in his Muranese glassworks with actress Kelly Lang, the famous “Brooke” of the American soap opera “The Bold and The Beautiful”. The actress, visiting Venice before Christmas of 1999, decided to visit the furnace of Archimede Seguso and to try glassblowing a glass vase. “Brooke” purchased several beautiful chandeliers for her home in America.

The traditional exchange of holiday greetings, 1999, was represented by a red Nativity under a huge bell-shaped chandelier in the same color. The Nativity was made by Antonio, reminiscent of the incantations of his grandfather Archimede.

Horse, 1965. Horse on a crystal iridescent trunk. I. cm. 37.

Collezione uova dell’anno: Hurricane. Uovo 1999 realizzato in cristallo con motividifiligrane cinquecentesche muranesi intrecciate. Ideazione Antonio Seguso.