NOTEBOOK 5

Another historic photo: it was taken on October 10, 1948 when the Murano factory, which is still operating, was opened. In the center, Archimede Seguso holding a glass… and with a little more hair. Since then Archimede Seguso has become a leader in the creation of artistic glass. The eighty five year old master glassblower is still making splendid sculptures which evoke admiration throughout the world.

PRESENTATION

YOU SPEAK IN GLASS

Glass: a culture in flux. This is the fifth edition of the “Quaderni di Archimede” and perhaps a placid philosophy has worked its way into these pages.

Symbol of the ephemeral and of persistence over time, of beauty expressed through light and color, hard and yet apparently fluid, glass is an artistic material that is particularly well-suited to the cultural turbulence of our day, so eclectic and in many ways ambiguous. Going beyond the commercial goals, these Quaderni have still another purpose: to make us think about the history of yesterday, and the history of today in the fabric of an artist like Archimede Seguso who has, without equal, interpreted the essence of glass in over half a century of what is already a historic production. It is an esthetic line, but there is something that goes beyond mere taste and wants to respond to authentic cultural stimuli.

After Quaderno N. 4 that was a monograph dedicated to the Lyon exhibition, we are returning to our more usual format.

The first part is dedicated to that fascinating subject, Carnival in Venice seen through Archimede’s glass; then another current topic – Easter, and Archimede’s original eggs. They have already become something similar to the ones made by Fabergé, and are highly sought after on contemporary collectors’ markets. And finally, notes on “Proposte d’oggi”, (Suggestions for today), with special emphasis on the success the “Rotture” cycle enjoyed at Lyon, in the Hermes Gallery, rue Auguste Comte, and the prestigious retrospective show set up in the Hall d’Honneur of the Credit Lyonnais.

CULTURAL NEWS

Bottles and glass amphora of alabaster pink, 1959, h. cm. 60, 50, 21.

THE AMBIGUOUS OF CARNIVAL

Three pink vases on the balustrade of the Palazzo Ducale, three “masked” appearances. The syndrome of doubling, glass as a truth and a lie. Pierrot drained by the jazz band. Color as a symbol of the ephemeral.

Paolo Rizzi

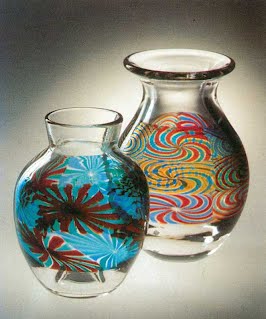

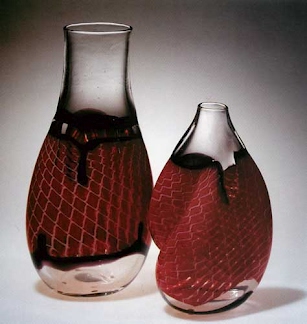

Vase “starry spring”, 1992, h. cm. 32×23, and jar “colored rays”, 1992, h. 27×20 cm.

Three pink vases on the balustrade of the Palazzo Ducale: the Basin of St. Mark, the island of San Giorgio and the tip of the Giudecca are opposite. It’s an old photograph from Archimede Seguso’s archives, striking mainly for the perfect harmony between the pink of the vases the blue waters of the lagoon, but, there is something else, something that goes beyond the blend of shape and color. There, off in the shadows, we can see the moored gondolas, and some “macchiette” (figures, as Canaletto called them) of people walking and gazing. And suddenly, the vases become figures, or at least anthropomorphic beings, signs of some human dialogue. What else? They are characters; I could even add that they are “masks”.

As George Simmel has observed, Venice has a strange and moving ability to reduce everything to its fleeting, prehensile, ambiguous nature. It’s the city that rose from the sea, like Aphrodite; it absorbs and encompasses sensations, transforming them into different states of mind. This is what has been defined as the “carnival syndrome”. Masquerading comes from the allusive quality, from psychological motility. It is the symbol of the dual nature: land and water; marble and air; substance and appearance; absolute calm and emotional vibration. We could even add Eros and Thanatos; Apollo and Dionysius. Opposites clash, but at the same time they merge… Truth or lies? As if to ask: what is more real the mask or the face?

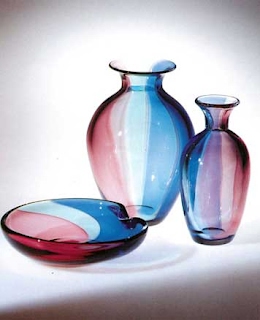

Vases and bowl, “Carnival”, 1989, h. cm. 20, 17, circ. 17. Cupped vessels, decorated entirely with longitudinal bands of ruby, green, blue glass, separated by amethyst wire.

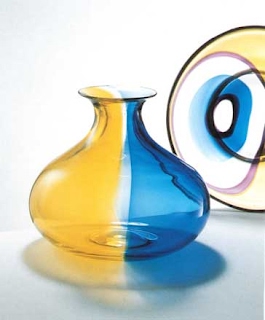

Vase and plate “Carnival”, 1989, cm. 26×30 and circ. cm. 33. Flask vase internally decorated with two vertical strips in yellow and blue glass that will fade slightly over a central strip of transparent glass. Yellow transparent glass plate decorated with concentric rings of amethyst crystal and blue glass.

Oddly enough, it is glass that best renders this dual nature of Venetian Carnival and not only symbolically. It is a hard yet fragile material, impenetrable, solid and yet transparent. It is the illusion, according to Thomas Mann of a topos which is atopos, that we want to flee from, like Medusa, and yet we end up by running headon into it. The pink vases inhabit this real yet imaginary city: they are as much part of it as the Pillars of Acre torn from their enigmatic history. When glass meets with Venice, and Venice is transformed during its illusory Carnival rites, we can see the Oriental mirage that Diego Valeri spoke of: the spell of the fata Morgana that prevents us from distinguishing the two horns of the dilemma. Precisely: substance or appearance? Ruskin saw “Cleopatra’s bluish veins”, shimmering on the golden Basilica’s marble. Those bluish veins are the threads, the filigree and the laces made of glass. Archimede Seguso understood this perfectly. In the ‘thirties or even the ‘forties, but mainly in that fertile decade of the ‘fifties he interpreted the themes of the Venetian Carnival. Pulcinella, Pierrot, “Sor Bonaventura”, Harlequin, domino, all became “excuses” for telling the story in glass.

Archimede Seguso l’ha capito perfettamente. Già negli anni Trenta o quaranta, ma soprattutto in quel fecondo decennio dei Cinquanta, egli ha interpretato il tema del Carnevale Veneziano. I Pulcinella, i Pierrot, i Sor Bonaventura, gli Arlecchini, le stesse bautte, diventano dei pretesti per raccontare nel vetro la fragilità esistenziale di tutto ciò che è sentimentalmente veneziano, legato quindi alla malinconia dell’effimero. Ecco un Pierrot disteso, trasparente con i suoi elegantissimi bordi e bottoni neri. Lo si osservi bene: non è un Pierrot, è il vestito di Pierrot. La fisicità è uscita: non ha volto. E’ rimasta l’anima, che pare sciogliersi quando i rintocchi delle Ceneri annunciano la fine della festa. Come non ricordare gli stupendi disegni dell’album che Giandomenico Tiepolo ha dedicato alla “vita e morte” di Pulcinella? Lui, Pulcinella, ride e sghignazza; poi si stende sul letto di morte con la sua smorfia triste.

Carnival 1971. Sculpture made in solid black and clear glass. After the carnival, the costume is abandoned by man.

Pierrot, 1952, h. cm. 29. Sculpture in solid clear glass decorated with white lace and black opaque glass.

The story of the existential fragility of all that is sentimentally Venetian, linked to the melancholy of the fleeting. Here is a Pierrot, stretched out, transparent with elegant black trim and buttons. Take a good look: it’s not Pierrot, it’s his costume. The physical is lacking, there is no face. The soul has remained and it seems to dissolve when the bells of Ash Wednesday announce the end of the holiday. How can we not remember the stupendous drawings in the album Giandomenico Tiepolo dedicated to the “life and death” of Pulcinella? He laughs and jokes, and then Pulcinella lays down on his deathbed with his sad grin. Let’s take another look at the glass sculptures of the “Carnevale di Archimede”. Their limitless joy always hides a touch of melancholy. Pierrots play and celebrate the ritual of the ephemeral. They are fully aware of it as we can see in the costumes that reflect the “regard interieur”, that is, the immovable profoundness of the psyche. The lucky Bonaventura knows that at summer’s end Proserpina will have to return to the night of Hades. And that apparently sensual gesture in the dance is nothing more than the restless vibration of the soul… Am I exaggerating?

Vase and bowl “Carnival”, 1989, circ. cm. 33, h. cm. 35. Vase and bowl, crumpled effect, their vibrant colors change from yellow to ruby red to blue.

Plate “starry spring”, 1992, h. cm. 9, circ. cm. 43. Flat clear glass internally decorated in the middle with four bands of polychrome watermark.

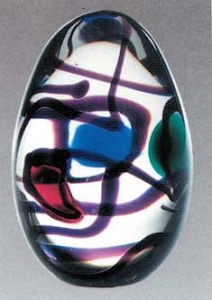

Egg “Carnival”, 1989, h. cm. 32. Egg of blown cobalt blue and ruby glass, crystal colored “eyes” and green outlined in amethyst elliptical glass tape.

“Pierrot”, 1957, h. cm. 31 h. cm. 21. Mask and opaque glass mask candleholder in white with ribbing and decorations in black opaque glass and crystal with gold.

“Guitti”, 1957, h. cm. And 20 cm. 29. Figures dressed in white opaque glass petal shapes with soft colors and decorations in gold crystal.

LOOKING TO THE PAST

THE MAGICAL EASTER EGGS

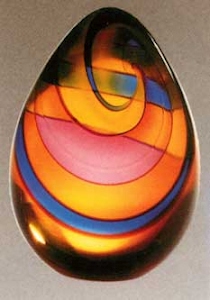

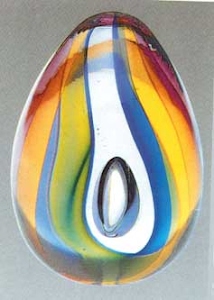

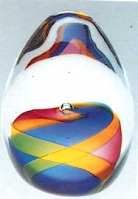

As of 1982, the production of a series which is increasingly appreciated by collectors is repeated. A challenge to pure geometry: extraordinary range of lights and changing colors, iridescent transparency and rhythmic quirks.

A Fabergé egg was the Tzar’s most precious yearly Easter gift to the Tzarina. Richness, and extraordinary artistic skill in addition to rarity have made Fabergé eggs one of the most sought after collector’s items in the world today. It is with a different spirit, but the same love of a beautiful object to be treasured that Archimede Seguso has been making his special Easter eggs since 1982. Every year he has made a limited edition of 130 numbered eggs (100 are marked with Arabic numerals and 30 with Roman numerals) which have become key items for glass collectors. This series stands in the front row in the showcase of the ideal museum of contemporary artistic glass.

We could say that Archimede’s egg is a challenge. It starts out with a fixed, immutable shape that is practically an archetype. No “plastic whim” is allowed: this is pure geometry. Therefore, the range of creative possibilities for artistic expression would seem restricted. But no, it focuses on an inner shape that becomes essentially light-color. Archimede’s eggs (as of now there are sixteen if we also count the “Harlequin”) are an exaltation of the intrinsic qualities of glass: where sculpture, if we can call it that, seems to be made by a laser beam, intangible, impalpable, almost beyond matter itself. A luminuous drop that maintains the nucleus of primordial, magical, and arcane vitality inside itself.

Only Archimede Seguso knows exactly how much extraordinary skill goes into each of these eggs. No two are alike: one plays with iridescent transparencies, another embraces curvy spiral rhythms; another draws a golden feather from the darkness of night; sparkling fluid in another; fascinating airbubbles; an exploding pinwheel of colored threads; a playful Flamenco rhythm; dual-faced with a magical mirror effect… and the latest. The latest, created for Easter 1995 is made of quick squirts of coral that rhythmically move in a context of golden crystal sections to the extent that they recall the nineteenth century painting technique known as pointillism (Seurat’s neo-Impressionism) that has cleverly been nicknamed as Pointy. Each egg is an invention; each egg is a way of making art. It’s curious, but readily explained. Where artistic qualities are combined with rarity, that is, absolute rigor in production, that is where collections begin. Archimede’s eggs, like (mutatis mutandis) Fabergé’s eggs are circling the globe. They are fought over by collectors. In some cases, the prices have quintupled. We are telling you this so that you can understand the love that surrounds Archimede’s magical art. Collectors love to keep these little jewels in their cabinets. It’s a “glance at the past” (although it be a recent past) that tells us how important it is for today’s people to surround themselves with something refined that creates a link between today and yesterday, between the neuroses of daily living and the comfort of timeless beauty. Refined collecting is like a bridge, suspended on the clouds of a reality that never dies. And one need not be clairvoyant to read the meanings inside Archimede’s eggs, wonderful eggs for coIlectors.

SUGGESTIONS FOR TODAY

THE SHOWING IN LYON

“Cavalli” “Horses”, 1994, cm. 34×48. Sculpture of the heads of horses in gold crystal solid glass on exhibit in the Hall d’Honneur of the Credit Lyonnais of Lyon for the showing “Archimede Seguso Maitre verrier a Murano”.

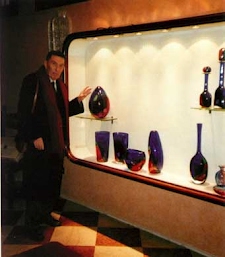

The flattering comments of the french public and press. At the center of interest is the retrospective exhibit set up in the Hall d’Honneur of the Credit Lyonnais. Received with great pleasure are “Rotture” and the traditional pieces.

Paolo Rizzi, as he previews the lastest creations by Archimede Seguso of the “Carnevale” series, in the Murano factory.

“Sculptor of light, the lastest master glassblower of Murano turns his works into a Venetian festival in which reflections of the Palazzo Ducale and the Rialto Bridge play together”. This is one of the many praises that appeared in the French press (this by Vidal-Blanchard in Progres) about the major exhibit Archimede Seguso held in Lyon between January and March, and to which we dedicated an entire special issue of “Quaderni”. We could say that it was a celebration, not only for Archimede Seguso, but for the entire splendid tradition of Venetian glass that is making a greater name for itself abroad than ever before. What most impressed the French public and we think it’s only right to mention – is Archimede Seguso’s quality workmanship as a sculptor, according to Vidal-Blanchard. Many have said and written the same thing in Lyon. It is not a question of a refined artistic craft, but authentic works of art made with the most unreliable material of all: glass. The works in the “Rotture” (Breaks) cycle that were shown in a separate part of the exhibit enjoyed most of the comments of this nature from both the general public and specialists.

The “Rotture” that we described at length in the first issue of “Quaderni” is a recent cycle that is still in production and still growing. Here Archimede gives symbolic interpretations of the esthetic and psychological characteristics of our era. Breaks, as scissions, tears, lacerations, restless signs of our times, splinters and wounds that encompass our existential destiny. Glass is no longer a compact mass that conceals precious lights, colors, practically unreal magic, inside itself. The mass breaks, it explodes into space into a galaxy of shattered light, creating deflections and transliterations, agitating vectors of force towards the outside along with magnetic forces pulling inwards… These are Archimede’s “Rotture”. In Lyon, as elsewhere, we have seen that they are the testimony of a social condition that extends to the psychology of our times.

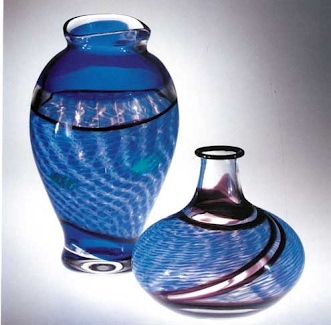

“vaso a rete”, mesh pattern 1989, h. cm. 36,5, I. cm. 18,5; “vaso riflessi”, reflections 1989, h. cm. 28, I. cm. 17.

“Leonardo”, 1991, h. cm. 35, I. cm. 23; “vaso sezioni tramate”, Woven 1991, h. cm. 22, I. cm. 23.

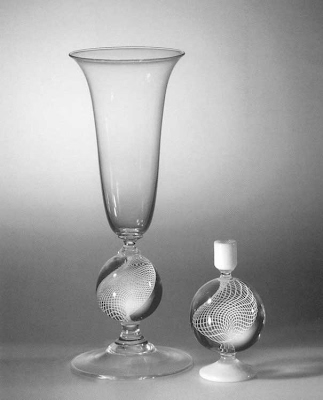

Vase, 1958, h. cm. 39, I. cm. 15,5, vase with stand in transparent glass; central sphere decorated internally with a twisted network of milky filaments. Candleholder, 1958, h. cm. 16,5, I. cm. 9, central sphere in transparent glass, decorated internally with a twisted network of milky filaments.

Back cover: Uovo 1995 “Pointy”, h. cm. 14. Egg, crystal and gold blown glass, with vertical ribbing decorated internally with touches of coral.

The Lyon exhibition, that closes on March 17 is but one milestone in the artistic journey that Archimede has undertaken. It will now travel and the next stops on the schedule are Lille, Zurich and Geneva. The “Rotture” will be joined by other cycles and other modes of expression created by the master such as, the table decorations that range from the large Veronese-style vases to innovative modern tableware. Nor will the latest “Intrichi” be left out: cobalt blue blown glass “bubbles” wrapped in crystal with coral and milky inlays. It will be yet another demonstration of Archimede’s lasting vitality.